Imagine if, whenever you went to your favorite bar, you ran the risk of your photo winding up plastered all over local media. Because of the type of bar in which you were spotted—because of the types of people it served—from that moment forward, your ordinary, anonymous life would cease. You’d lose your job, your family would disown you, you’d be an outcast and a laughingstock. How would the disgrace, however undeserved, make you feel? It would certainly make it hard to participate in everyday society; it might make life seem not much worth living at all.

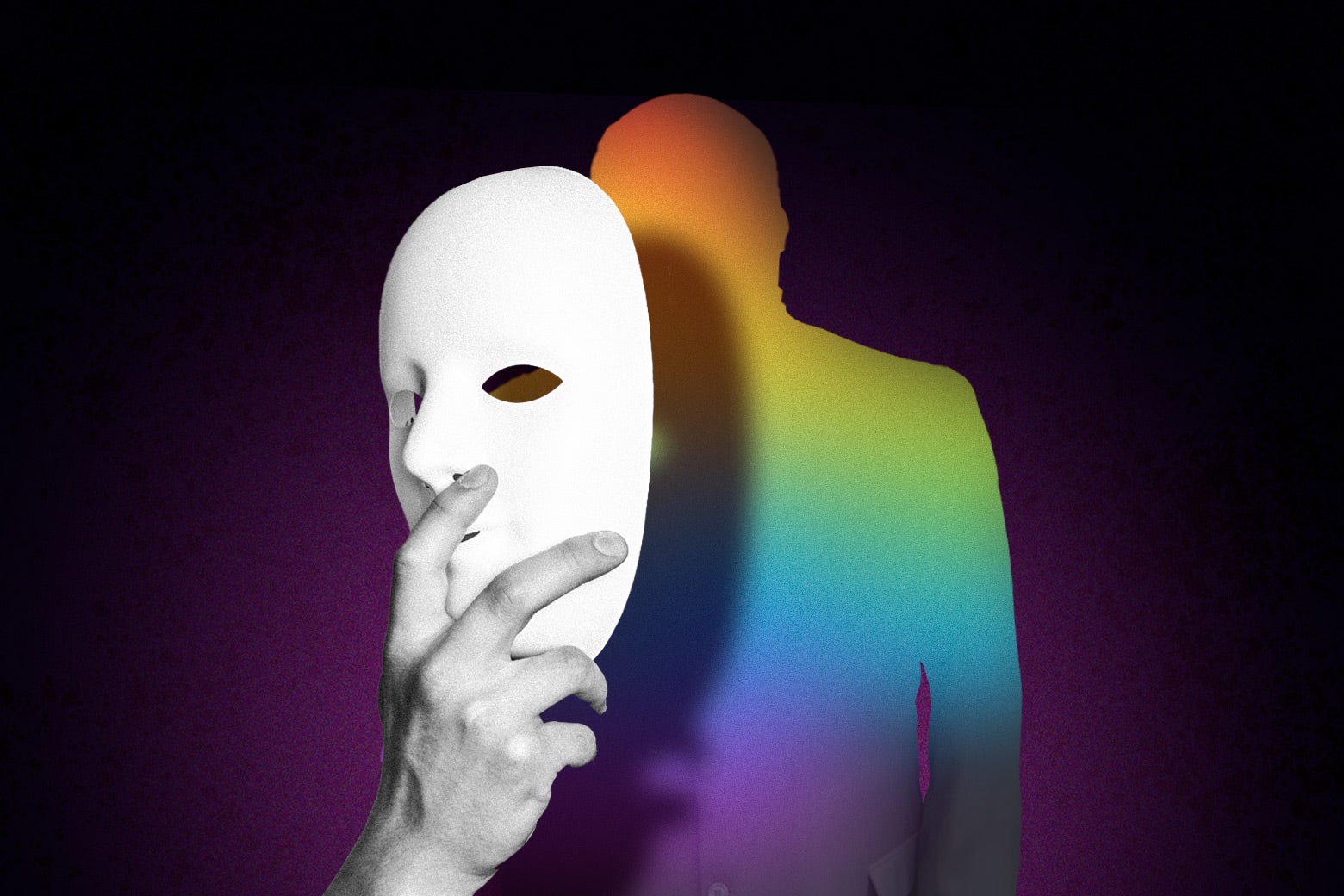

This—an ever-present fear of outing, social condemnation, and personal ruin—was the lot of gay men and gender-nonconforming people before Stonewall, when the riots in 1969 kicked off an era of resistance. And it’s a regime of terror that parts of the right-wing media are now trying to bring back where they can, sometimes with deadly consequences.

I was put in mind of the history of pre-Stonewall outing after following the story of F.L. “Bubba” Copeland, the mayor of Smiths Station, Alabama, who died by suicide this past fall after a forced outing campaign by a conservative site called 1819 News. The first story, published on Nov. 1, featured numerous pictures of Copeland, a local pastor as well as politician, dressed as a woman. The article revealed that Copeland maintained an Instagram account and online presence under the name Brittini Blaire Summerlin. In public life, Copeland presented as a heterosexual man with a wife and three children. On private social media accounts, Brittini presented as a transgender woman.

In my work running the trans news site Assigned Media, I focus on monitoring these sorts of stories in the right-wing press, which is why I learned about this early, after a freelancer tipped me off to it on Nov. 2. It was just one of a few stories we batted around as possible topics for her Friday column. I was sickened by a passage that described how Copeland deleted the accounts when confronted by 1819 and begged the reporter not to make the information public, so I passed on covering it, hoping not to bring the story further attention.

By Friday of that week, 1819 had followed up with four more articles: On the negative reaction of Alabama Baptist church leadership (Copeland’s denomination); Copeland’s sermon after the outing, in which he said “a lot of things that were said were taken out of context”; conservative radio’s harsh response to the story; and additional revelations on the contents of memes and erotic fiction Copeland had also posted, some of which mentioned or used the pictures of local residents. (In a meme pretending to show before-and-after photos of someone who had transitioned, Copeland used photos of a local brother and sister. A short story described a character’s fantasy of killing and taking over the life of a local businesswoman.)

By Friday evening, after five stories in three days and in a climate of intensifying harassment and mockery, Copeland was dead by suicide. The death happened in front of police, after a slow-speed chase by officers who were attempting to complete a welfare check. Friends had grown increasingly worried about the well-being of the mayor, but weren’t able to prevent the tragedy. After Copeland’s passing, he was remembered as a committed public servant who cared deeply about Smiths Station and its community.

I read ugly hit pieces targeting the trans community every day in my work at Assigned, but this one felt different. It involved a person with no support or connection to the LGBTQ+ community, deeply embedded in conservative Southern culture, whose life was ruined by an outlet with no legitimate news interest. While later descriptions of Copeland’s misuse of local people’s photos and the creepy erotic story went outside of what I’d consider ethical, the dresses and engagement online as a trans woman were the clear red meat of 1819’s coverage. The whole situation didn’t feel like a 2023 story at all, but something antiquated, from a time when people were regularly outed, their lives and careers ruined under a pretense of upholding moral values. What does the return of an outing-motivated suicide, decades after that sort of story had been relegated to the dustbin of gay history, say about where some in the online right want our culture to go from here?

To answer those questions, I decided to consult some historians to better understand what life was like for LGBTQ+ people before Stonewall. I reached out to Charles Kaiser, a journalist and the author of The Gay Metropolis, a history of gay life since 1940, and Jules Gill-Peterson, an associate professor of history at Johns Hopkins (and Outward podcast co-host) whose new book on the history of trans misogyny will come out later this month. I asked them to describe the climate and culture where the humiliation of public outing had once routinely defined people’s lives, and sometimes led to their deaths. What I found was that my sense that Copeland’s outing resembled this earlier era was accurate.

“There were approximately four people who were out of the closet before 1960,” Kaiser told me: Allen Ginsberg, James Baldwin, John Rechy, and Gore Vidal, “sort of.” (Vidal had a male partner and wrote about sexuality, but did not identify with the word gay.) In the time before Stonewall, Kaiser explained, outness was yet to exist as a valued or even coherent concept—being hidden was “part of what it meant to be homosexual.” As a New York Times reporter in the 1970s, Kaiser shared that he too had lived a closeted life at the time, with the understanding that if his sexual orientation became publicly known, he’d be fired.

“In most major metropolitan areas, in the 1950s and ’60s, if there was a raid of a gay bar, the names of those arrested would be published the next day in the newspaper,” he said. This was essential “if you had any ambitions to do anything,” he explained: “Even the people who wrote West Side Story, all of them were in the closet.”

Gill-Peterson has studied the papers of Don Lucas, one of the leaders of the “homophile” movement, which was a precursor to the modern gay rights movement. She found that the noted homophile group the Mattachine Society identified shifting press coverage away from sensational outing stories as one of its key goals. “It’s the press that was the central vehicle, where this outing took place,” she said. “The police would call a local beat reporter and tell them to come down: ‘We’re raiding this bar, come down with your camera.’ ”

The Mattachine members saw changing the press coverage of homosexuals as important, alongside forming relationships with police departments, because it was the press, as much as the police, who held their community in such terror. After a raid, whether or not those detained by the police were charged or arrested, police would make everyone they’d caught stand in a line. These lineups routinely included people identified as men wearing women’s clothing; “impersonation” was a misdemeanor offense. It also made for a more lurid picture. The local beat reporter would snap a picture, police would pass on the names, addresses, and workplaces of each person, and all of that would go into the paper. The next day it would be public, and they’d all be fired, if they had steady work to begin with.

The fear, and the excitement, of doing something with this level of risk defined gay life in the post–World War II period. Kaiser described an informal rumor network that sought to establish which bars were raided regularly and limit the danger, but ultimately, chance played a huge role in who was outed and who wasn’t.

This happened at a time, not dissimilar to our own in some ways, when much of America was gripped by an obsession with policing gender roles and sexuality. The disruption of the war had led to more gay men finding one another and to women working outside the home, wearing pants, and supporting their families. The consequences for those who strayed from “tradition” were public, swift, and intense. And for those made an example of, suicide sometimes followed.

It’s impossible to know how many victims of these outings killed themselves, but Kaiser and Gill-Peterson said that deaths by suicide were always part of the narrative. “There were no straight allies. Gay people talked about it with themselves, people in the community discussed it, but there was no sympathy,” Kaiser said. “In the public, it was understood that since this was a mental illness, a response, perhaps the most likely response, to being outed was that they would want to kill themselves.”

When it comes to documented cases of suicides, we know that some occurred during what’s now called the Lavender Scare, part of the 1950s Red Scare, where hunting and outing gay men in government jobs was presented as a matter of national security that went hand in hand with fighting communism. (The period was recently dramatized in the Showtime series Fellow Travelers.) This practice was justified because gay men were vulnerable to blackmail, a self-fulfilling prophecy if ever there was one. It was during this time that suicide became inextricably linked to the gay experience in the wider public consciousness, because of a few high-profile suicides connected to the Lavender Scare, including the suicide death of a U.S. senator, Lester Hunt, whose son was actually the one arrested and outed as a gay man.

In America today, so much has changed that it might seem ludicrous to say that I fear a return to an environment like the 1950s and ’60s moral panic over homosexuality, with its climate of secrecy and fear, and the central role of the press in driving harassment, humiliation, firings, and sometimes suicides. In parts of the country where LGBTQ+ acceptance is firmly ensconced, there’s likely not much conservatives can do to roll back the tolerant attitudes decades of activism have won. But in other places where extremists have taken over governance, LGBTQ+ life, particularly trans life, seems much more precarious than we might have thought. For example, in Florida, trans teachers are already facing laws restricting what pronouns they can be called at work, and perhaps whether they can teach at all. If such laws drive more and more trans people into the closet, lower public visibility may lead to less social understanding and acceptance, driving a vicious cycle where the consequences of outing grow more dire as time goes on.

“I would think that trans people now, clearly, have the closest experience to what gay people had in the 1960s, in terms of the fear your existence activates in the population, and the cynicism of the right wing in exploiting that,” Kaiser said.

As for Bubba Copeland, I don’t want this story to be taken as an attempt to place the mayor in a particular identity category or make his death represent a political argument. But the moral panic over transgender identities, which has stirred so much anger and hate for trans people, was clearly fuel for the outing that ended in Copeland’s suicide. Whether Copeland was a closeted trans woman, a gender-nonconforming man, a crossdresser, a hobbyist, a fetishist, or whatever else, an online presence that described “Summerlin” as a “transgender curvy girl” was what made the mayor a target. (1819 News did not comment on criticism of the articles, but did offer “thoughts and prayers” in a statement.)

Copeland’s death comes in the context of an ongoing campaign by an emboldened, socially conservative right that openly seeks to bring back a regime of shame, self-loathing, and terror of being outed. When GOP politicians pass laws seeking criminal penalties for teachers and librarians for sharing “sexually explicit” material—and then define any mention of gay or trans people as “sexually explicit” or “pornographic”—they’re seeking a return to the pre-Stonewall climate. When they make discussion of sexual orientation or gender illegal in schools, they’re seeking a return to the pre-Stonewall climate. When they attempt to ban drag performances, they are seeking a return to the pre-Stonewall climate.

The practice of press outlets terrorizing gender-nonconforming people over their private lives should have stayed in the past. That it could not only happen in 2023, but even end in suicide, should be a wake-up call for where the far right hopes their attacks on the trans community will go. Copeland hailed from the sort of small Southern town where attitudes about the LGBTQ+ community have changed the least, but attitudes aren’t static. Escalating attacks on the trans community, combined with laws designed to humiliate and stigmatize trans people by taking away the ability to change legal documents, barring trans people from using public restrooms, banning positive depictions of LGBTQ+ people in school libraries, forcing trans teachers to misgender themselves in class—all of these measures seek to drive trans people out of public life in these places. Several Republican candidates for president in 2024 have made these their implicit or explicit nationwide plans, if elected.

When people can’t exist openly in public, their true selves fight to be expressed in private, which leads to double lives marred by shame and fear of being exposed. Those are the toxic conditions some now seek: conditions in which outing can serve as the ultimate punishment for queer existence, threatening people’s social acceptance, their livelihoods, and even their very lives.