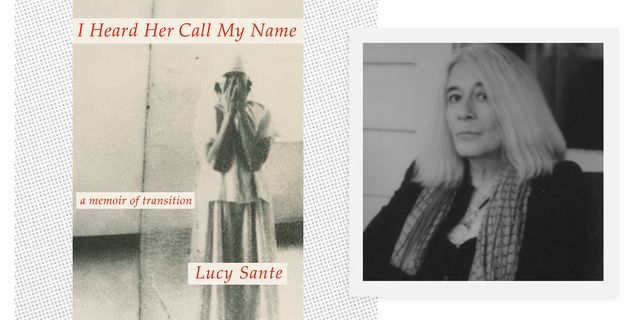

Esteemed scholar and cultural critic Lucy Sante—who is also an award-winning author and photographer, and a former professor at Bard College—opens up about her later-in-life gender transition in her memoir I Heard Her Call My Name. Below, an exclusive excerpt.

Not long after my egg cracked I began wondering just how it had happened. I knew the mechanics of it, beginning with FaceApp—but what had primed the pump? I began collecting microscopic clues as they occurred to me. It seemed significant, for example, that I had not long before moved four of my favorite stuffed animals from their bag in the attic to the top of my dresser. That kind of display was something I had long avoided. Then there was the fact that the previous autumn I had played Shulamith Firestone in a student movie. All I had to do was wear a long black wig and a pair of plastic glasses and read an excerpt from her teenage diary, but it gave me pleasure. Maybe, too, I was inspired by the then-current streaming series The Queen’s Gambit, based on the Walter Tevis novel about a girl chess master, with its commanding performance by Anya Taylor-Joy as the prodigy. I identified with it in strange ways, badly wishing to be that character, for all her flaws.

Quite a few of the people I came out to wondered if the coronavirus and lockdown had anything to do with the cracking of my egg. I didn’t immediately think so, because I was lucky enough not to be very much affected by it: I have a house, work at home anyway, don’t socialize overmuch, and live in a nice town where few people walk, so was able to get regular exercise by hiking all over its far-flung neighborhoods. But then Mimi suggested that my egg might have cracked because I finally felt sufficiently comfortable, and she had a point. We had just enjoyed a very snug year. Mimi had returned after six or seven months of attending to her dying mother and then fixing up her house after she died. It was a relief for her to get away from all the family drama, and it was a relief for me to have her back. We cocooned, as they say, making a garden, cooking, adopting a puppy, entertaining ourselves. Aside from the fact that we weren’t having sex, it was as happy a coupledom as I had ever experienced. But would that have been enough to tip the scales?

The most striking feature of my metamorphosis was its absoluteness. The edifice of denial went down as quickly and definitively as the Berlin Wall, and then I started telling people right away. I did not leave myself a back door. My gradually expanding view of how gender dysphoria had permeated my life was breathtaking; there seemed to be no domain unaffected by it. Instances ranged from the tiny and trivial—my discomfort when shirtless, hatred of boxer shorts, avoidance of bodily ornaments—to the major and obvious. There were defenses built to conceal the secret, and other defenses to hide those. I was never at home in my body, did not know what to do with it, was always awkward and clumsy because I could not enter into a rhythm, had to force myself to move, stand, sit in ways that would pass, or at least not draw attention. I had been laughed at often enough as a child. (Thanks to Eva, I came to realize that dancing was a furlough from that jail.)

There was not a second of my life when I wasn’t pinned under the klieg lights of self-consciousness. Even when I was alone I was being watched. My mother’s shadow was hovering, of course, but I was the one watching me, anticipating all the watchers in school and at work and on the street. I was so good at self-policing I could have saved the taxpayers money. But when I was out in public my preparations were all for naught. There were just too many watchers, and I couldn’t properly account for, let alone adjust to suit, every individual point of view I might encounter. This one might think I was too effete but that one might think I was too clerkish. It didn’t matter whether the watchers were friends or strangers, people I was attracted to or felt nothing for, long-term acquaintances or people I’d never see again. And all the while I was continuing my immigrant studies in sociology and culture, which meant never letting on that I didn’t already know whatever I was just learning—there was that whole other impersonation I was carrying on concurrently. Barring grocery lists, I never wrote anything down that I would have been unwilling to have published. I curated my surroundings as a kind of rebus of cultural signs, displaying faceup those items that would send a message about my judgment and my possession of secret knowledge. Nothing was left to chance in my world, except maybe furniture. I was trying at all times to mount a production titled Luc, written and directed and produced by and starring me, as I wanted to be seen, although I never got the impression anyone actually saw me that way.

And I hid out a lot, sometimes spending so long without seeing other people that when I did finally go out into the world again I felt as if I’d forgotten how to talk. In the days before answering machines I’d often put my phone in the refrigerator. Telephones scared me because they were somehow so intimate, also because the ring always sounded like an invasion, also because if you called somebody you could never be sure who would pick up. (My parents didn’t get a phone until I was eight. When it rang, which was seldom, it would usually be in the middle of the night, someone calling from Belgium to announce a death.) I was forever claiming that I had no friends, whereas in reality I had at least a dozen people, maybe more, who would have called themselves my friends, and who would have come to my aid if I had asked for it. But I couldn’t risk asking for help if I needed it. I had to keep a certain buffer between me and others. When I did socialize I was performing, but couldn’t always withstand the rigors of the craft, and when that happened I had to isolate. Very few people ever saw me cry, and I tried to avoid it even when I was alone. (I cried a lot as a child, but on the threshold of adolescence took a vow never to cry again, and kept it up for at least five years.) I realized that sharing feelings with others could be cathartic and helpful, but my secret most of the time blocked the way.

I knew all of this about myself, but did not truly appreciate it until transitioning lifted the veil. Suddenly I could see the entire panorama: the effects of my mother, those of my experiences as an only child and an immigrant, and those of my secret. I had lived in the United States for sixty years by then, and my mother had been in her grave for twenty, so perhaps those influences were weakening. But the weight of my secret could not be underestimated. I could fully measure its effects as they left me. I no longer felt timid; I didn’t give a hoot about being judged; I felt like I owned my body, maybe for the first time. So many things about my new being felt familiar, as if I were remembering them. It appeared that transitioning did not involve piling on additional stuff; rather it was a process of removal, dismantling the carapace of maleness that had kept me in its grip for so long. As a trans woman I might now and then feel freakish, or horribly clockable, or out of place, or resented, but those were all projections from without. In and for myself I did not have a speck of doubt. I had once described myself in print as a creature made entirely of doubt, most of it self-doubt, but I had now been given something like a Euclidean proof of an essential truth about me.

By April I was bursting with the need to tell people. I was high atop the pink cloud, that phenomenon known to trans and AA people alike, and filled with missionary zeal. I kept marveling at my own behavior. I had always thought that if by some weird chance I ever found myself transitioning, I’d be slinking around, lurking in the shadows, wearing shapeless clothing to hide my shame. Instead I was pretty much forcing myself on people; I wanted to be seen. I sought invitations; I wanted to strut. (I recalled the stunt Peter Cook pulled in the early 1970s, when he dressed up like Garbo and had himself driven around London in an open car while he shouted, “I vant to be alone!” through a bullhorn.) This newfound extroversion did not apply to the supermarket or the lube joint or walking the dog, all of which was potentially hostile territory. But I was fortunate enough to have a fairly significant pool of people who might be on my team, whether out of friendship or human-rights sympathies. So I kept thinking of new people, new crowds, new clusters I could come out to, and when I did I’d send them some version of the letter.

What I was seeking, of course, was affirmation. Despite my ironclad conviction, I still required proof. Hence my 127 daily trips to the mirror, which may have doubled after I started on hormones, to see if anything had changed. And I needed others to mirror me too. One old acquaintance, who herself had begun transitioning until she realized that testosterone was changing her voice—she was a singer—was particularly adept at playing along, flattering, bestowing pet names, giving fashion tips, and generally engaging in campy girl talk (until she withdrew her favors because I wouldn’t leap a loyalty hurdle she’d erected). I debated the meaning of gender with Sara for months until we finally agreed it was silly putty. She was virtually the only person I got any sort of pushback from: Why couldn’t I just be androgynous? But since she was one of my oldest and dearest, I knew what prompted her reaction and took no offense, and it helped me to talk the matter through with her. Others further out on the rings of acquaintanceship were less helpful. Why don’t I shave my head like this beautiful African American twenty something? Why not cover my cranial nudity with a cloche hat? Maybe I’d like to drive over sometime and pick through a vast collection of secondhand polyester wigs. Maybe I’d like to join this venerable transvestite dining club in midtown. Maybe I’d like to meet their transgender friend who used to be a cop and now lives in the woods.

From I HEARD HER CALL MY NAME by Lucy Sante, to be published on February 13, 2024 by Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2024 by Lucy Sante.