In February 2023, Chrissie and Daniel took their son, who goes by the nickname Z, in for his annual gender affirming care check-in with his doctor. In the months leading up to the appointment, the tension had been building in their house. Tennessee’s state legislature had introduced SB0001 that fall, which would ban gender affirming care for minors like Z. At that point, he’d been receiving care for about a year, and he started coming home from school stressed and overwhelmed. “He’d tell us, ‘I can’t get away from it,’” Chrissie says. “‘My teachers are talking about it. Everyone’s talking about it. There’s no escape.’”

But his annual appointment was routine and uneventful. Afterward, the family started to feel more settled, and Z’s mental health seemed to lighten. “I think there was a part of us that really didn’t think it was gonna happen,” Chrisse says. And then, just days later, SB0001 passed.

Barely two months later, on April 6, 2023, their doctor sent Chrissie and Daniel a certified letter to their home in Knoxville, Tennessee. “Dear Children’s Hospital Patient and Family,” the letter read. “Due to the new Tennessee state law SB0001…East Tennessee Children’s Hospital is unable to continue your treatment for gender dysphoria.” After listing the services that they could no longer provide to patients like the their kid — estrogen, testosterone, and puberty blockers — the letter went on: “For continued treatment, you will need to seek care out of state.”

The bill wouldn’t go into effect until July 1st, but the letter marked their last appointment. “They basically gave us a letter and said ‘Good luck,’” Chrissie says.

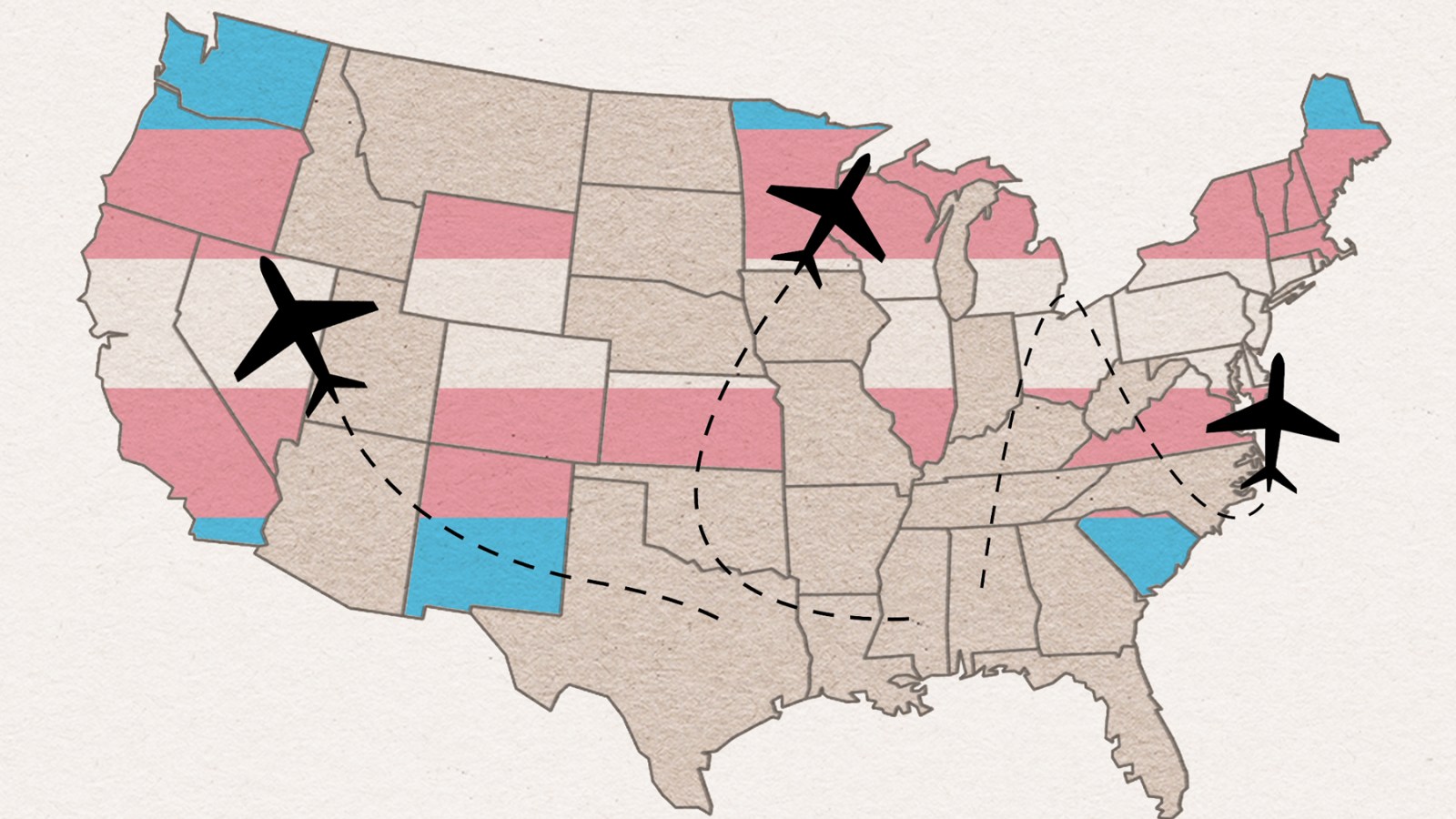

As bans on gender affirming care for trans youth are signed into law across the country, families like Chrissie and Daniel’s are facing new and constantly changing obstacles to accessing vital healthcare. Twenty one states have enacted laws that restrict care, and the highest concentration of these bills are where Chrissie and Daniel live, in the South. In this region alone, more than two thirds of states have an active ban as of Jan. 1, creating a sprawling landmass — more than 1.1 million square miles, larger than the entire country of Mexico — that families have to get through in order for their kids to access care. And it’s not slowing down: in the first eight weeks of 2024, as many of last year’s restrictions have gone into effect, state legislators have already introduced 121 new bills targeting trans healthcare. “As more and more trans youth age into care and their parents realize that the closest place they can access it is a flight away,” says Allison Scott, Director of Impact & Innovation at the Campaign for Southern Equality. “The need is vast, and it’s only going to surge further in the months ahead.”

The barriers are financial, practical, and legal, and they are intentionally difficult to work around. Some of the restrictions impact insurance coverage, others have made providing gender affirming care a felony, and all of them go against every major medical association’s guidance by restricting access to medically necessary care. In the face of these obstacles, families, doctors and advocates have spent the last year cobbling together an emergency grassroots network providing transportation, financial assistance, guidance, and medical care to make sure trans youth are able to continue to access the gender affirming care they need.

In the months after Chrissie and Daniel opened that certified letter from the Children’s Hospital, they received an emergency grant from a regional advocacy group to cover costs to travel to a new provider, but they still had to figure out where. First they considered New York — it’s a sanctuary state so they could reliably get care until their kid turned 18, but could they afford to fly there every three to six months? Next the family’s nurse practitioner suggested St. Louis — it’s closer, about an eight hour drive, with a huge network of resources for trans adolescents — but the very next day, Missouri’s legislature passed their own ban on gender affirming care. “Part of the problem is that everything is happening so quickly,” Daniel says. “Even the places that have traditionally been safe places aren’t anymore.” Next they looked at a clinic in North Carolina, just one state over — if they got in before their ban took effect on Aug. 1, they’d be protected by the grandfather clause, at least for now.

The trans community in the South isn’t small: there’s an estimated 102,000 trans youth in the South, and more than half a million trans adults. And a support network has risen up in the face of these bills to help them get their children through the last year: local groups have built an emergency grant program to help families access out-of-state care, telehealth companies have found creative ways to provide access with less travel, and volunteer pilots have come together to fly patients to providers in other states.

But what happens next? Rolling Stone talked to five families (some of whom asked to use either their first names, or a different name, to protect their families’ privacy) that have been in the South for generations, about how they’re facing these impossible questions — about the meaning of home, the meaning of safety, and their identities as Southerners. “It’s not just that we’d have to drive across state lines,” Daniel says. “It’s that we are choosing care for our child — with the guidance of medical professionals — but when we come back, we know we’re coming back to a state that has legislated that our child shouldn’t exist.”

A protestor’s sign reads, ”Trans youth deserve better,” at the Texas State Capitol building on March 27, 2023.

A protestor’s sign reads, ”Trans youth deserve better,” at the Texas State Capitol building on March 27, 2023.

All five families were very clear that it would be a mistake to claim that the South is inherently inhospitable to trans kids. They all have communities and support networks in their home states that are loving and accepting of their kids. “If you look on a map, Tennessee is very red,” Daniel says. “But it’s not 100 percent red — it’s 60/40, you know? There are more people that think like us than it seems like when you look at a map.”

He blames the shift on a very vocal political minority. “The negative voices are getting louder and louder,” he says. Listening to a misinformed, hateful minority try to speak for his family has changed the way he moves through his community. “I’m angrier than I used to be,” Daniel says. “And when politicians are saying that people like us, our child, are bad, evil, demonic — it’s scary for us to parent our child in that environment. Just go into the mall or the grocery store, we worry that something could happen.”

“I bet you, in a few years, all of these politicians will have moved on to the next thing,” says Molli, who’s been navigating these restrictions with her trans 13-year-old in Texas. “Everyone will have forgotten about this, and our lives will have been drastically changed.”

THE FIRST BILL THAT BANNED gender affirming care for minors was signed into law in Arkansas in 2021, and since then, with the help of model legislation from hate groups like the Family Research Council, 35 states have seen a version of that ban introduced onto the floor of their state government.

Every version of the bill bans access to hormone treatment and puberty blockers — a drug that delays puberty until a trans child is ready to decide if they want to take hormones — for trans minors (as well as banning surgeries like breast augmentation or phalloplasty which, to be clear, are not included in the typical standard of care for adolescents.) Many of the bills include other dangerous misinformation about gender affirming care — claiming, in one example, that the risks for the care are unknown, that providing it doesn’t improve the mental health of adolescents, and that “the majority come to identify with their biological sex in adolescence or adulthood, thereby rendering most physiological interventions unnecessary” — disregarding the fact that the American Medical Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the American Psychiatric Association all consider it to be part of best medical practices.

Conservative politicians have invested hundreds of thousands of dollars to convince their legislatures that trans medical care is a threat to their children. The bills purport to protect kids from making permanent life- and body-altering decisions treatments before they’re ready — and to protect them from needing to have corrective surgery later in life. But research has found that 98 percent of trans adolescents continue their gender affirming care as adults, and as Molli Lobos, a parent of a trans 13-year-old boy in Austin, Texas, puts it, making her son go through puberty as a girl would lead to permanent changes in his body, too.

Molli hadn’t been paying close attention to Texas’s ban — or any of the others, nationwide — as it moved through the legislature last year. Her son Jack had been seeing a trans-affirming therapist and pediatrician since he was seven years old (around the time he wrote a letter to his older brother, sharing his new name and asking if it was okay if he was his brother now, too.) They were just gearing up to start puberty blockers, with the full support of his doctors. So when Texas’s healthcare ban was introduced, Molli told herself not to get worked up — she’d seen similar bills try and fail in Texas before, and she didn’t want to get caught up in the fear mongering.

But when she watched it get signed into law in June — and her child’s doctor was suddenly fired in an investigation by the state — she knew it was a crisis: Jack was now 13, and she was already sending him to school with pads in his backpack “just in case” he began menstruation, a possibility he was dreading with every fiber of his being. With puberty looming, Molli immediately started emailing everyone she could think of. “I’m a ‘Help me’ person,” she says, waving her hands around her head. “Help, help, help!”

One of those emails was to the Campaign for Southern Equality. The Asheville-based advocacy group was among the first responders to this crisis: Less than three months after the passage of 2023’s first healthcare ban, the organization launched the Southern Trans Youth Emergency Project, a resource that provides emergency grants and logistical support for families in states with new bans. They collaborate with local organizations all over the South, using a public health model called “hub and spokes.” “We can operate as a regional hub,” says director Jasmine Beach-Ferrera, “and then we’re connected to the local spokes that are doing frontline, hometown work.” Since last March, they’ve supported more than 500 families and provided $400,000 in grants to families in need.

Advocates gather for a rally at the state Capitol complex in Nashville, Tenn., to oppose a series of bills that target the LGBTQ community, Tuesday, Feb. 14, 2023.

Advocates gather for a rally at the state Capitol complex in Nashville, Tenn., to oppose a series of bills that target the LGBTQ community, Tuesday, Feb. 14, 2023.

Like so many families in the South, Molli’s biggest hurdle was distance. As each ban passes, families are being forced to travel farther and farther to access care. In other parts of the country, families can, at the very least, depend on neighboring states with shield laws that protect access to trans healthcare. While many of them are in predictably blue strongholds — covering the West Coast and the Northeast — some, like Arizona, New Mexico, Minnesota, and Illinois, are pressed against red states, making it possible for families to consider staying close to home. The Southern states, though, don’t have a single shield law among them.

That means that with every passing ban, families will have to stretch farther and farther out of their communities. Right now, a trans kid in Miami would have to travel seven hours to get across the border to a major city in Georgia. But the moment Georgia’s temporary injunction is overturned, that trip stretches another hundred miles to South Carolina. From Houston, a family would have to travel 400 miles to the nearest clinic in the middle of Arkansas, where a judge deemed their ban unconstitutional, but the state hopes to get it reinstated. From Molli’s home in Austin, Albuquerque was their best bet — 700 miles away.

Molli couldn’t drive across the wide expanse of West Texas, but there’s a resource for that, too. She was directed to Elevated Access — a group of some 400 volunteer pilots dedicated to getting people access to healthcare out of state. Volunteers have been flying patients around the country to get chemo or access blood products for decades, but Elevated Access was established explicitly around bodily autonomy. The group was founded after the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision allowed states to heavily restrict abortion access, and they quickly expanded their work to include gender affirming care. “We’ll assist people in states with bad laws, whatever the reason, to get to the healthcare they need,” says Fiona, a spokesperson for Elevated Access who asked to only be identified by her first name.

The group uses small propeller planes (not much bigger than a crop duster) to pick up patients at any of the nondescript regional airports found in virtually every county in America (think Westchester County Airport, not JFK.) With their volunteer pilots on call, they can hop you across state lines to your appointment, and get you home within a few hours. When a patient is referred to them, they’ll either set up a private flight from a small municipal airstrip, free of charge, (“some passengers have said they feel like Beyonce,” Fiona says) or, if it’s safe and more affordable, they’ll foot the bill for a commercial flight.

Unsurprisingly, demand for flights to safe, accessible gender affirming care is on the rise. To protect patient privacy, the pilots never know what type of care they’re transporting their passengers to. Cielo Sunsarae runs the Queer Trans Project, an advocacy group based in Florida, and the largest referrer to Elevated Access for gender affirming care. “There’s been a steady increase in need,” he says. They’ve orchestrated over 22,000 miles of travel for trans patients, just since last November.

Back in Texas, Molli finally had all of the pieces of her plan in place: a commercial flight to Albuquerque set up through Elevated Access and a grant in hand from the Campaign for Southern Equality to help with the other travel expenses. But even with a fleet of 400 volunteer pilots on your side, planning in this constantly-changing landscape can be nearly impossible. As the appointment approached, the clinic suddenly canceled her appointment. They didn’t feel confident that they could safely navigate their insurance with Texas’s new law in place.

Molli had to hit the phones, again, and that’s when she found QueerMed.com. On a call just before their first appointment, she says, “I think it might be a miracle.”

QUEER MED IS THE CHILD of necessity. Dr. Izzy Lowell was running the only gender clinic in Atlanta in 2017, when one day, a patient was late for his appointment. “I was annoyed because it was before lunch and I was hungry,” Dr. Lowell says. “I went into the room and he stood up and he was like, ‘Dr. Lowell, I’m so sorry I’m late. I drove from Nashville, Tennessee, to get here.’” The patient couldn’t get gender affirming care in Nashville so he had gotten up at 6 a.m. that day and driven almost four hours to get to his appointment. “That really put things into perspective for me,” Dr. Lowell says.

That’s where the idea for Queer Med began — an all-telehealth resource for gender affirming care to fill in the wide chasms in the country where clinics weren’t yet banned — they just didn’t exist. They’re now finding a new demand for their clinic, as families who once had access to care are watching it slip away.

Sophie (who asked that we not use the names of her or her family for their safety) found Queer Med after a ban was signed into law in February in her home state of Mississippi. Her daughter Allie had started presenting as female when she was in first grade — wearing her hair long and dressing in feminine clothing. But she didn’t find the words for her identity until she was eight, when she saw a video on YouTube that defined “transgender.” “She was like, ‘That’s me! That’s it!’” Sophie says.

They went to see an endocrinologist for the first time when Allie was 10. Living on the Gulf Coast, access to gender affirming healthcare had always been a matter of distance. There was only one clinic in Mississippi that would see patients younger than 16, and it was three hours away, in Jackson. When Sophie and Allie first started looking for care, the best option was an hour away, in Mobile, Alabama.

The first sign of trouble came after their second appointment. “We received a bill from the pediatrician for $300,” Sophie says. “And I was like, ‘This should have been covered under my health insurance. Why am I paying for an office visit a year ago?’” She learned that the appointment had been coded with a referral for gender dysphoria — the standard diagnosis for people seeking gender affirming care. With that code, their insurance wouldn’t cover anything.

Leviathan Myers-Rowell, right, looks back at his mother Jodi Rowell, left, and calls out to her as he leads a march of transgender youth, their families and supporters from the Mississippi Capitol in Jackson, Wednesday, Feb. 15, 2023.

Leviathan Myers-Rowell, right, looks back at his mother Jodi Rowell, left, and calls out to her as he leads a march of transgender youth, their families and supporters from the Mississippi Capitol in Jackson, Wednesday, Feb. 15, 2023.

Twenty four states explicitly prohibit trans exclusions in health insurance, but none of those states are in the South, which means insurers can choose to not cover gender affirming care. And in Sophie’s home state of Mississippi, the law explicitly allows private insurers to refuse to cover anything coded with gender dysphoria.

With a ban in Alabama looming, Sophie started looking for care to the east, 45 minutes away in New Orleans. “We found a doctor at Children’s Medical Center of Louisiana that specializes in gender care — a whole team with psychologists and the endocrinologist and the coordinators. It’s amazing. So we’re like, okay, that’s where we’re gonna go.”

At their first visit, the doctors at the Louisiana clinic laid out Allie’s care plan: They told Sophie that Allie would have to stay on puberty blockers until she was 16 or 17, much later than her old doctor had suggested. And then came the cost: If they got the blockers in the mail and administered the medication themselves, the hospital said, it would be $25,000 every six months. If they chose to have it done in the hospital, the price tag would go up to $50,000, not including travel.

The cost of puberty blockers is unpredictable nationwide. There are only a few FDA-approved brands, and depending on what one you’re prescribed — and whether or not insurance will cover it — a single dose can cost anywhere from $4,600 to $45,000. “We just don’t have that money in the bank,” Sophie says. “We had just accepted that we were going to be those people that live in medical debt for the rest of our lives.”

Sophie considered going to Mexico for care — the flights back and forth would be cheaper than the cost of the drugs they were offered. But then she found Queer Med. In addition to being a hub for telehealth care, they also have a workaround for insurance discrimination: a membership system and a self-pay model. For Sophie, all she and Allie have to do is hop across state lines and sit on her phone in a parking lot, and it took her annual estimate from $100,000 a year down to $400.

A clinic like Queer Med is uniquely positioned to provide gender affirming care where it’s needed most. It’s not state funded, they don’t have brick-and-mortar locations that can be targeted by AGs or protestors, and they operate in 25 states, concentrated in the areas where care is under attack.

The model also becomes an antidote to all of the state-based clinics that have ended care preemptively — like Chrissie and Daniel’s clinic in Knoxville and Molli’s in Austin. Most states’ bans have an explicit effective date, and many have a window to “wean” adolescents off their hormone treatment. But many clinics are seeing the writing on the wall, and closing soon after the bans pass. Because they’re not based in a single state, Queer Med has more flexibility. “The wording of a lot of those ‘detransition’ clauses is that your patients should be weaned off of their medications as soon as it is medically safe to do so,” Dr. Lowell says. “And in my opinion, that’s never. So I’m gonna continue to provide care until midnight on the day I legally can’t do that anymore.”

AT FIRST GLANCE, THE SCRAMBLE to get access to gender affirming care looks a lot like the fallout for abortion after the Dobbs decision — desperately pulling together funding and transportation to get people to the healthcare they need. And all of these families were able to pull of a magic trick last spring and summer by cobbling together emergency resources to make sure their children are safe and cared for. But now that they’ve gotten their first appointment, their first dose, their first treatment plan, the similarities to abortion care end. Because unlike abortion, gender affirming care doesn’t have an end date, and these families will have to keep figuring this out, year after year.

Because of that, in every conversation with these families, the possibility of moving out the South floated to the surface. All of the families we spoke to were generational Southerners, with siblings and parents and deep roots in the region, so it’s not a straightforward call: Chrissie and Daniel plan to stick it out — they have a strong community in Knoxville, and their kid thinks leaving would be more harmful than dealing with anything the state wants to throw at them. Molli would prefer to stay in Austin, but she’s worried that they won’t be able to pull from the same resources a second time, so Oregon is in the back of their minds. Sophie and her husband have discussed the possibility, but “Honestly, one of the reasons we haven’t created a really clear cut strategy yet is because so many states are doing this now,” she says. “There are fewer and fewer safe places for us to be.”

Shelby — the mother of twin 13-year-olds — saw the writing on the wall in Tennessee early on. Her daughter Claire had socially transitioned when she was 10, right before Covid lockdowns started. “We had this beautiful opportunity to spend those few months with one another, going through this transition period,” she says. “And when they started sixth grade, Claire went back to school as Claire.”

But just a year later, last March, Tennessee’s ban passed. “Everything was changing daily,” Shelby says. “So that was when we were like okay, we have no choice. We need to find a place to go.” Like many of the families I talked to, they also pulled out a map of “safe states” for trans people. They landed Illinois — the closest state to Tennessee with a shield law in place. By the time I spoke to them last June, they were in the middle of their move.

People dance together while protesting bills HB 1686 and SB 14 during a ‘Fight For Our Lives’ rally at the Texas State Capitol on March 27, 2023 in Austin, Texas.

People dance together while protesting bills HB 1686 and SB 14 during a ‘Fight For Our Lives’ rally at the Texas State Capitol on March 27, 2023 in Austin, Texas.

The decision wasn’t easy: they left a whole life behind in a matter of months. “My brother and his wife live in Tennessee, and have two children. I want to be there to watch them grow up.” But she took comfort in the fact that Chicago’s nearby, and her family would hopefully come visit. “Everyone loves Chicago, right?”

In Mississippi, Erica and Rick Barker had hoped to not have to make the same decision. The Barker’s twins, Max and Mylah, are both genderqueer: Max is nonbinary, and Mylah is trans. They go to separate middle schools in Jackson, Mississippi, and they’re both the only out, genderqueer kids in their schools. Erica is a paralegal for the ACLU in Mississippi, and she consistently took their schools’ clunky, outdated policies about bathrooms and dress codes as an opportunity to show her kids how they can challenge a system.

But with Mylah just getting ready to start gender affirming care, the healthcare ban wasn’t a teachable moment for the Barkers — it was a sign to leave.

“I pulled up a map, and showed them states that we could possibly move,” Erica says. “We went through that with them, looking at the states that have protective policies already in place, where we would all be safe.” Rick hates the cold, so that ruled out the East Coast. They’d considered moving to California in the past, but the cost of living was so much higher. Then they looked at Nevada: it was warm and it had a shield law, plus Rick and Erica had gotten married in Las Vegas, and Max is a diehard Drag Race fan, who would love a chance to actually see a show.

Things moved quickly from there. By the end of the summer, Rick had found a new job in the Las Vegas area, and was moving there first to figure out the best area for the family to land. And Érica started reckoning with leaving her job at the ACLU — perhaps the hardest pill to swallow. “This is one of the first times where I have thoroughly enjoyed what I do,” she says, “and I feel some definite purpose.”

They’d hoped to wait until the end of the school year to move the kids, but Erica says school was starting to become untenable for Myla, being “purposely misgendered by peers, teachers, and school administrators.” They already had the groundwork set to make the move, so they sped up the timeline. “We had enough and decided to let them both finish the first school semester in MS and we’d get them outta there,” she says.

And with that, the Barkers became one of the countless families of Southerners pushed out of the South by this wave of legislation. As the pieces fell into place, Max was the most disappointed. They’d hoped to take on the state’s new healthcare ban with the same attitude that they took on the bathroom rules and dress codes: “Fight it from the inside,” they said.

Mylah was curious what it’ll be like to meet other out, queer kids. “It’ll feel so good to be able to be myself,” she says, “instead of having to hide myself. I think seeing more people be like me will help me become more me.”