K.A. began to socially transition in the beginning of 2019 after shaving his head. He initially asked his friends to address him using they/them pronouns, then they/he pronouns, while also asking to be called by a different name. Eventually he realized that he preferred he/him pronouns and his birth name. “Coming out as transgender is not as easy as saying ‘I want to be a boy,’ it’s a whole process of looking at yourself and figuring out who you want to be,” K.A. said. (Photo by Nance Beston | Byline Magazine)

K.A.walks into the bathroom at his dad’s house, flicks off the overhead light and closes the door. He plugs in a dim disco ball that speckles the bathroom walls with blue, purple, green and pink. More than a year ago, K.A. began showering in the dark like this, dreading this part of his morning routine.

He carefully avoids eye contact in the mirror, but if he catches a glimpse of himself, he presses his breasts down to see what it would be like if he had a flat chest. He finally steps in the shower.

Warm water streams down his skin as K.A. begins his hygiene regimen: face care, shampooing and conditioning his hair. Then, K.A. starts to wash his body. He aims to finish this task swiftly to avoid discomfort, especially surrounding his chest. Sometimes, if he’s not quick enough, tears stream down his face.

He turns the water off and wraps his towel snugly around his chest. He then darts to his adjacent bedroom.

After closing his bedroom door, he squirms into his binder, a black compression tank top, with beads of water still dotting his skin. He faces his full-length mirror, adjusting his chest until it appears as flat as possible.

Now content with how he has hidden his breasts, he gets dressed, swapping clothes until he feels like he looks masculine. Before leaving his room, he checks the mirror one last time.

“The binder would already cause me to start slouching,” K.A. said. “But at least nobody could see I still had breasts.”

K.A., a transgender Montana teen, had been planning to get top surgery before his high school graduation this spring. But after the Montana Legislature passed a bill threatening his ability to do so, K.A. and his family were left scrambling.

Grappling with dysphoria

Gender dysphoria is recognized by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders and is defined as when someone’s gender doesn’t align with their body — breasts or lack thereof, body and facial hair, voice pitch, face shape and genitalia are some examples of specific characteristics that can cause gender dysphoria.

The Williams Institute of University of California, Los Angeles Law reports 0.5% of adults in the U.S. identify as trans, or around 1.3 million people. It’s estimated there are 500 trans teenagers in Montana, which is 0.78% of minors.

Trans people in the United States are four times more likely than their cisgender counterparts to be the targets of violent crime, according to Williams Institute. K.A. is a pseudonym, as he asked to be anonymous for safety reasons and his friends and family will only be referred to by first name.

Two years ago, at age 15, K.A. found himself grappling with serious anxiety, depression, self-harming and discomfort in his own body. To cope with his mental health struggles, K.A. was prescribed Prozac and attended weekly therapy sessions.

K.A.’s parents tried to work with a mental health facility when he shared he had suicidal ideations, but because they were just ideations and not attempts, the facilities were unable to help.

“I wanted to take the pain away,” K.A.’s mom Kerstin said. “I wanted to make it better. I wanted there to be a quick and easy answer. I know the self-loathing involved when you self-harm from experience. So knowing that K.A. was feeling that horrible pain was really, really hard.”

On an especially difficult day, K.A. decided he needed a significant change, so he shaved his hair down to a buzzcut. He realized the more masculine look brought him comfort. Then, he began to socially transition, asking his friends to start using “he” and “him” pronouns. Socially transitioning is when an individual starts to live according to their gender identity by changing forms of gender expression such as name, pronouns, clothing and hair.

In April 2019, K.A. publicly announced his trans identity during a school walkout. At that point, only a few friends knew about his gender identity. “I honestly think I may be a trans-man,” K.A. said during his speech. “That is like the first time I have said that.”

His sister recorded the moment and, with K.A.’s permission, showed it to both parents.

“I want to say that it caught me off guard, but it kind of didn’t. Like we kind of also saw it coming. It did kind of get heavy on my mind,” Kerstin said. “Because I know what happens to some people in some states and cities and how awful the hate can be. So, I was afraid for K.A.”

K.A. called his dad, Jerry, and told him over the phone. Jerry said he loved K.A. and nothing would change that.

“I wish you would have been born in the body that you want it to be in,” Jerry told K.A. “But you know, either way, God loves you.”

Where it all began

K.A. began attending sessions with a gender-affirming therapist in August 2021. After months of therapy and a series of discussions, his therapist, K.A. and his parents decided it was appropriate for him to start hormone replacement therapy.

“K.A.’s mental health was declining quickly, and I didn’t want to lose (him),” Kerstin said. “I’d rather have him as a him than not at all and I want him to be happy. There’s no point in being in this world and being unhappy.”

His inaugural testosterone dose was Dec. 10, 2021.

“It was a really exciting day, because I was at school the whole day and I was just anxiously waiting to get out of school, go pick up my prescription and shove a needle in my leg,” K.A. said. “Which isn’t my favorite part, fun fact. I kind of hate that part. But I liked the testosterone part.”

The following injections were self-administered every Friday before school. A few months later, K.A. noticed biological changes — his menstrual cycle stopped, his voice deepened and facial and body hair emerged. These transformations boosted his overall well-being, leading him to decide to stop taking Prozac.

“If I had gone this long knowing my identity, but not being able to have the changes that I’ve had, I would not be as happy,” K.A. said.

K.A. said he began to feel more comfortable in public places after starting testosterone treatments. His circle of friends expanded and he discovered a love for school, particularly choir, orchestra and drama, prompting him to plan for a career as a music teacher.

“My confidence had a big impact, especially before I started testosterone because I had a squeaky voice like I was a soprano one. I knew that I wasn’t passing and I just didn’t feel confident to talk to anybody besides my, at that point, small group of friends,” K.A. said. “But once I started being on testosterone, my voice lowered. I was passing more, my confidence just immediately went off. I used to have really bad social anxiety, but it’s basically ultimately gone at this point.”

Weekly testosterone injections steadily improved his well-being, yet one barrier remained — a longing for top surgery. Desire for a flatter chest was driven by daily discomfort from wearing a binder and constant dysphoria surrounding his breasts.

The binder increased K.A.’s neck problems, resulting in migraines that would drive him into a dark, quiet room for relief. He wished to stroll down the school hallway, his mind on classes instead of the anxiety he felt over whether others were fixating on his chest.

“I look at my face and I know that I’m a boy, I feel like I’ve looked like a boy. But then I see my chest and it just does not match with what I know I am and what I feel like I look like otherwise,” K.A. said. “It’s like my body was mixed up.”

Plans derailed

K.A. planned to undergo top surgery, the process of removing breasts for a more masculine chest, prior to graduating high school. However, the passing of Senate Bill 99 derailed his plans.

SB99 was introduced to the Montana Legislature on Jan. 3, 2023. The bill called for banning access to any gender-affirming care for minors, including hormone replacement therapy, surgeries and hormone blockers in cases that treat gender dysphoria.

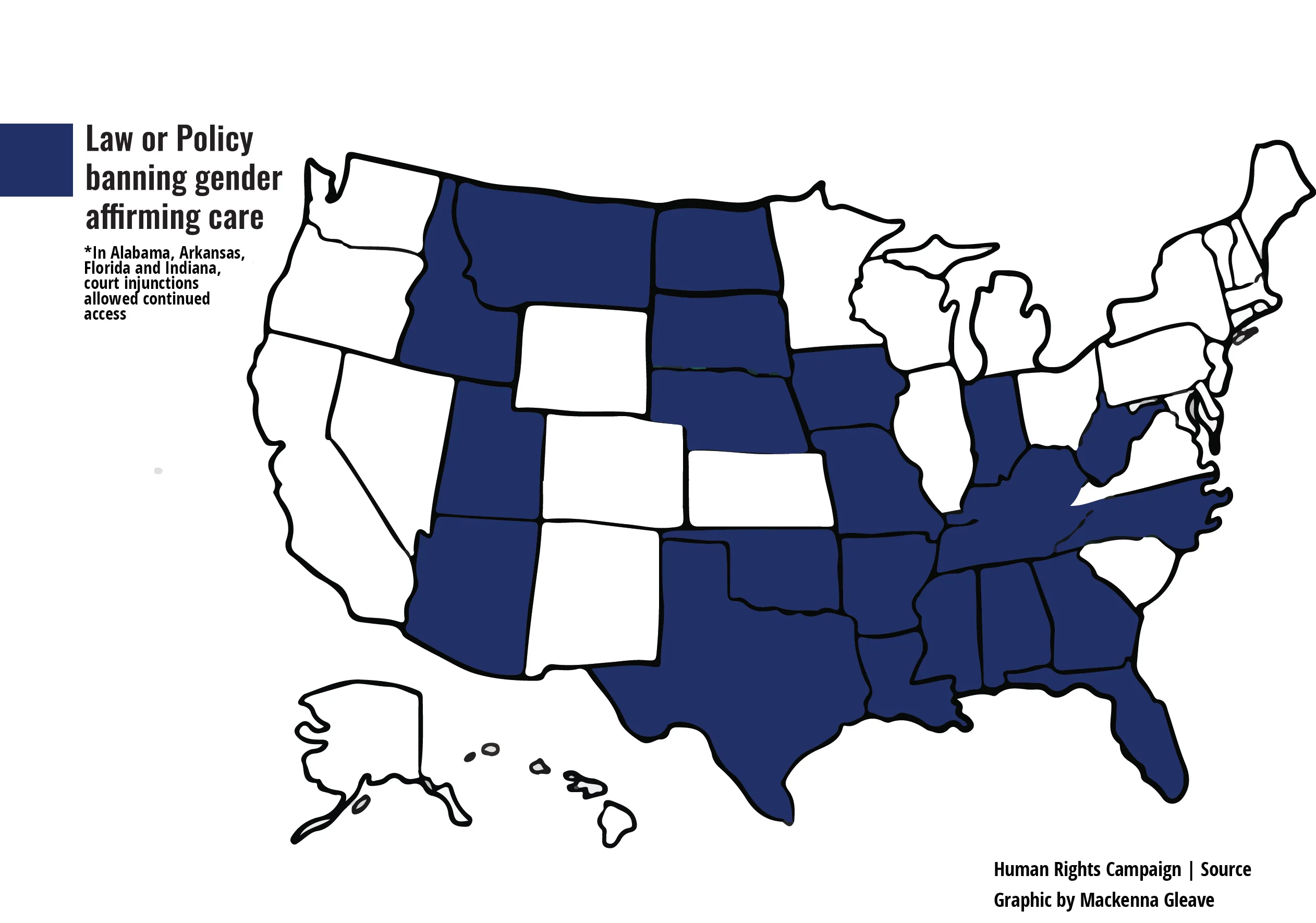

Under the bill, any doctor who performs a banned procedure can be sued, fined and could result in a year-long suspension of their authority to practice. Twenty-two states had similar bills introduced in 2023.

Democrat Zooey Zephyr was the first trans woman elected to the Montana Legislature. The 2023 session was her first. When SB99 went to the House, Zephyr spoke out against it.

“When you pass these laws you get trans people killed. When you bring these laws, trans people get killed,” Zephyr said.

Montana legislators received a letter from an ER physician during the session, who said they were seeing an increase in suicidality among trans youth.

Representatives later voted to ban Zephyr from the House Chamber after she said, “I hope the next time there’s an invocation when you bow your heads in prayer, you see the blood on your hands.” The House Speaker justified the ban, saying Zephyr had violated “the rules of decorum.” Zephyr said she doesn’t regret her statement and stands by it to this day.

SB99 passed and was signed into law by Republican Gov. Greg Gianforte. It was scheduled to go into effect on Oct. 1, 2023.

Top-surgery was always part of his plan

K.A. found a doctor who specializes in cosmetic, plastic and reconstructive surgery last September. K.A. and his parents rushed to schedule top surgery before SB 99 took effect. Payment for the surgery required out-of-pocket funds, totaling $11,200. With an eight-day window between finding the right doctor and the law’s implementation date, the family needed to secure the funds and pay the entire surgery cost.

“I was given the quote and then went home to my mom. I was in tears when I got the quote. I was in tears when I was talking to my mom. Like, surgery was always part of the plan,” K.A. said. “But the state, they cut off everybody who was already in the process of getting this done. Including somebody who has already been taking testosterone for a couple of years and they just, like, stopped (gender-affirming care), just like, no consideration for anything.”

The family did not have the funds to pay for his surgery. Jerry, K.A.’s father, said that given a couple more months, he would have sold his new motorcycle and other things around the house to ensure K.A. could get his surgery. They discussed loans, but approvals would take too long. Kerstin proposed a different strategy — launch a GoFundMe campaign on social media to help pay for the medical bill.

“This was, like, our last chance, I was like, holy crap, they’re going to win. The state is going to tell me what medical care my kid can have,” Kerstin said. “That wasn’t a good feeling. We had to fight that.”

On the GoFundMe post on Sept. 20, 2023, K.A. wrote, “Having this surgery now would save me from another year of constant dysphoria, distress and discomfort. I can’t imagine spending so much more time suffering like this.”

After it went live, K.A. obsessively checked his GoFundMe campaign. One day before they needed the funds, K.A. was still $2,275 short of his goal and he went to sleep not knowing if he would be able to get the surgery. But the next morning, K.A. discovered an anonymous donor paid the remaining sum.

“People they didn’t even know donated money to my kid so he can have medical freedom,” Kerstin said. “It was just an overwhelming sense of love and support from the community.”

‘Happy no more boobs’

On Sept. 26, K.A. awoke at 4:30 a.m., after a restless night with little sleep. It was the day of his surgery. A day filled with nerves, but also immense excitement. K.A. arrived at the hospital at 5:45 a.m., scheduled for the day’s first operation. Accompanied by his anxious parents, K.A. prepared for the transformative procedure.

After a 30-minute wait, K.A. was brought into the back. The nurse had him put on a yellow gown before he went under anesthesia. As the nurse wheeled him to the surgery room, K.A. said he remembers being very happy, giggling and saying “hi” to every passerby. He fell asleep before entering the room.

K.A. woke up three-and-a-half hours later, fairly high on the anesthesia drugs, his chest wrapped with a bandage and drainage tubes sitting on his lap.

“I don’t remember much after the surgery, but the first thing I remember was I looked down and I could kind of see under my bandages and I started crying seeing my chest because…my chest, it was flat,” K.A. said. “For the first time ever, it was just flat.”

Jerry said there were a lot of emotions in the room, but those emotions and K.A.’s reaction convinced him and Kerstin that they had made the right decision.

“People can say that it was a choice and that I shouldn’t have allowed (the top surgery) to happen,” Jerry said. “But what’s a year difference gonna make? Why make this person suffer for another year?”

The World Professional Association of Transgender Health showed few people regretted their decision to receive gender-affirming treatment. The study showed that getting early medical help, as part of a complete plan focusing on feelings about gender and wellness, can help many trans people who want to seek gender-affirming treatment.

K.A. went home to his dad’s apartment that afternoon and both of his parents helped him get comfortable in the recliner. His mom left for the night but sent him messages. Before K.A. fell asleep, tired from the big day, his friends sent him a video singing a parody of “Happy Birthday” with a chocolate ice cream cake that read “Happy no more boobs” in blue frosting.

The very next day, a district court temporarily blocked SB99 from becoming law. Three families with trans children, two medical providers who work with trans youth and three organizations including LAMBDA Legal, the American Civil Liberties Union and ACLU of Montana sued the state.

Missoula County District Court Judge Jason Marks sided with the plaintiffs, saying SB99 appeared unconstitutional, would infringe on fundamental rights and fail to protect minor children from harm.

Living in the unknown

Jerry assisted in cleaning K.A.’s post-top surgery wounds for the following weeks, taking special care to prevent any infection in the cuts and his re-positioned nipples. His older sister sent him daily texts asking him how his nipples were. His friends remained supportive throughout, flooding his phone with motivational messages and calls.

“He is more himself than I have ever seen him be, and I have known him for ten years,” Ashley, K.A.’s best friend, said. “I think having that care has helped him through all of it. I can’t imagine where he would be today if he didn’t have that care. He would still be K.A., but he wouldn’t be fully himself because he would still be struggling with a lot of that dysphoria along with the mental health impacts of not getting that care.”

After his surgery, K.A. was out of school for three weeks. He took the time to admire his chest, work on homework and relax. He was given the OK to return after his surgeon removed his drainage tubes.

When he returned to school that Friday, all of his teachers and friends were very excited to see him again. He was glad to be back in classes, especially choir class. He said he loved talking to his friends over the phone, but he really missed singing with them. For the first time in his high school career, he was able to wear a button-up with nothing underneath it.

Now, the only worry K.A. has about his care is the future of his testosterone treatments. He said he has anxiety about the possibility that SB99 could go into effect any time and what he and his parents will have to do to ensure he still gets testosterone.

K.A. said that it’s frustrating that the Legislature tried to ban his care instead of applying restrictions on who can access the care. K.A. was in therapy for multiple months before starting hormone replacement therapy. Then, he spent almost two years doing HRT before he got top surgery.

If SB99 goes into effect, both parents agree they will figure it out. They won’t allow K.A. to lose that part of his health care, but it would be incredibly stressful. As SB99 remains temporarily blocked, there is not much they can do but wait.

A light in the dark

Showering has now become one of K.A.’s favorite things to do. He enters the bathroom, undresses and plays his favorite indie music. He has retired the disco ball, keeping the overhead light on. Before he even turns on the water, he admires himself in front of the mirror — flexing and checking out his chest. He flips between full-front view and sidelong looks, admiring his flat chest, healing nipples and a developing six-pack.

He steps into the shower. The warm water runs down his skin, like it did before, only now he can appreciate his body. He says during the shower he carefully traces his scars multiple times.

“I love it so much,” K.A. said. “Getting in the shower like I have no worries. I’m just singing along with my little songs because it’s fun now and not as a distraction. I can actually look at myself and feel good about myself when I’m in the shower.”

After he finishes his shower, he ties a towel around his waist. He returns to the mirror, water droplets still dotting his chest. He struts to his bedroom with his towel still casually draped around his waist.

Then he picks out what pants he wants to wear for the day. Before he finishes dressing, he massages his scars in front of the mirror, part of his post-surgery care. He puts antibiotic ointment on his finger and gently rubs it in circles on his scars and nipples for about 10 minutes. His discarded binder lays crumpled on the floor, never to be worn again.

Eventually he picks out a shirt, appreciating how the fabric feels against his bare skin.

Before he leaves his bedroom, he gives himself one last glance in the mirror. Then, he walks out of his bedroom with his head held high.

Our stories may be republished online or in print under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. We ask that you edit only for style or to shorten, provide proper attribution and link to our web site.