For two years, Vicky has been held in Immigrations and Customs Enforcement detention without any opportunity for a hearing.

Vicky — whose lawyers asked that her last name not be published to protect her safety — is a transgender woman who came to the U.S. looking for safety. Instead, interactions with law enforcement and her longtime confinement have caused irreversible harm and left her uncertain of her future, she says. Now, Vicky has a legal team pursuing a claim for protection, and they finally secured a hearing to consider her release in a couple weeks.

After fearing for her life due to threats of violence against transgender people, Vicky first fled Honduras as a teenager in 1994 and came to the U.S.

But because she didn’t speak English and didn’t have a support system, she was labor trafficked, and she was convicted of a drug offense. This ultimately led to her deportation to Honduras in 2016.

Vicky continued to fear for her life while back in Honduras, so she left again in August 2019 to try and come back to the U.S. in search of safety and support. But she was charged with illegal reentry, and she’s been detained in one way or another since. She served time for an illegal reentry conviction, and then got transferred to ICE detention, where she has been held without any kind of hearing since March 2022.

“The treatment that Vicky has faced in detention has been just adding on layers of punishment and cruelty to Vicky’s experience,” said Jesse Franzblau, a senior policy analyst with the National Immigrant Justice Center.

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX

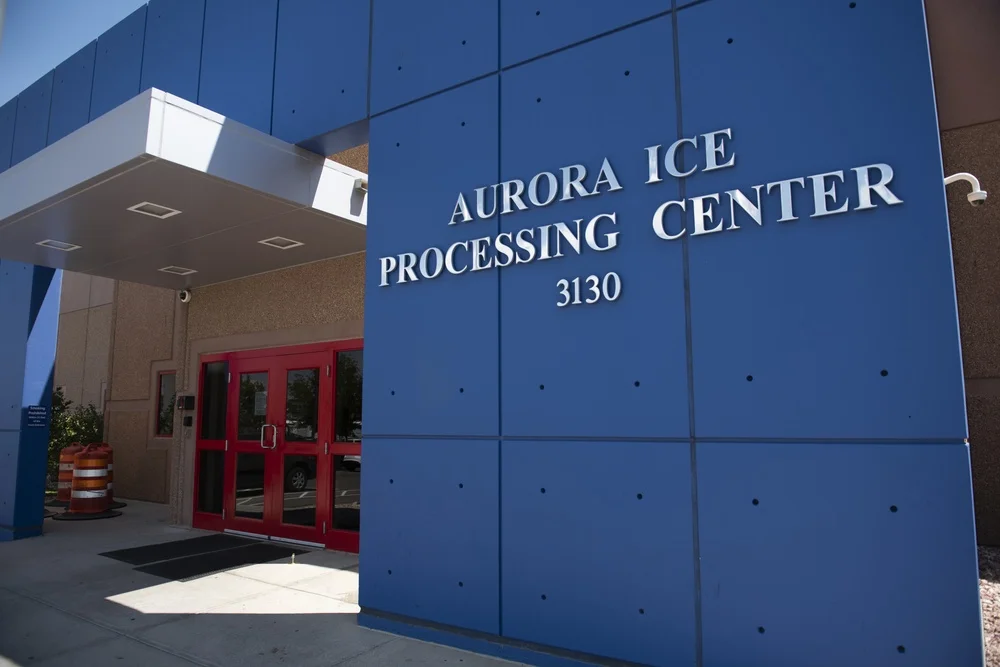

Before her transfer to the ICE detention center in Aurora, where Vicky now lives in a pod specifically for transgender people, she was at the Pine Prairie facility in Louisiana, where ICE forced her to live in the male unit. ICE has 43 people who identify as transgender in its custody, with 11 of them detained in Aurora. Congress recently required ICE to report data on gender identity, but Franzblau said it’s likely an undercount as many people may not be comfortable self-identifying.

Both facilities Vicky has been detained in are owned and operated by the private, for-profit GEO Group on behalf of its client, ICE. Pine Prairie has a history of alleged abuse and neglect, which led a variety of civil rights groups to file a complaint with the Department of Homeland Security. The Aurora facility has a similar track record of abuse and mistreatment complaints as well.

The treatment that Vicky has faced in detention has been just adding on layers of punishment and cruelty to Vicky’s experience.

– Jesse Franzblau, senior policy analyst with the National Immigrant Justice Center

The NIJC also filed a complaint with the Department of Homeland Security’s Civil Rights and Civil Liberties while Vicky was still at Pine Prairie because of how difficult it was for her to live day to day. ICE placed her in the male unit despite knowing she is a transgender woman. She was told her only option if she didn’t feel safe with the male population was to live in solitary confinement — an offer she took up. After the NIJC filed the complaint, she was transferred to Aurora.

“At that time, Vicky was afraid to even let other people know that she was trans, and so she hid that and then was basically put into solitary and suffered really severe mental decline because of that, being placed away,” Franzblau said.

ICE spokesperson Steve Kotecki said the agency is committed to ensuring its detainees “reside in safe, secure, and humane environments.” He said transgender detainees could be at any ICE facility around the country, as a dedicated housing option is not always an option due to circumstances including unit capacity, the person’s preference, the safety of others, as well as community or family ties in other areas.

“ICE regularly reviews each case involving self-identified transgender noncitizens and determines on a case-by-case basis whether detention is warranted,” Kotecki said in a statement. “Transgender noncitizens, like all noncitizens, may be housed in a separate or dedicated unit, with the general population, or in protective custody. ICE does not maintain LGBTQ+ pods in any ICE facility. Instead, ICE maintains a dedicated housing unit for detained transgender women… in the Denver Contract Detention Facility in Aurora, Colorado.”

The Aurora facility is home to the only transgender-specific unit in the country.

The treatment Vicky has experienced inside privately owned ICE facilities has led to a severe decline in her physical and mental health, she says. She struggles to communicate with others and finds herself isolated, even within the transgender unit in Aurora. She also can’t see properly, because ICE hasn’t given her the proper glasses prescription for over a year, and she hasn’t been treated for dental issues causing her pain, she says.

Vicky told Newsline through her legal team that being detained is “horrible” due to the mistreatment and a lack of appropriate medical attention, among other concerns.

“Multiple due process violations”

Morgan Drake, an attorney with the NIJC, started working on Vicky’s case in September 2022. She is helping Vicky apply for protection under the Convention Against Torture, an international treaty agreement that says the U.S. and other countries involved are not allowed to send anyone back to a country in which “they credibly fear they will be tortured,” Drake said.

Vicky initially filed an application for protection under the convention without help from an attorney in spring 2022, Drake said. At the time Vicky was at Pine Prairie, so she applied on her own because she didn’t have access to immigration attorneys and didn’t know how to find one.

Drake said the immigration judge denied Vicky’s case, which is common for cases filed without an attorney, and she faced several due process obstacles when she applied for protection. The NIJC legal team started supporting her ahead of the appeals process. The first time around, the Board of Immigration Appeals sent Vicky’s case back to the original judge, who again denied her case.

“She has been repeatedly victimized by multiple members in both the community in Honduras and in the United States and by the United States immigration system,” Drake said.

Now, the NIJC team is helping Vicky through a second round of appeals. In early March, the board determined the immigration judge “erred in multiple ways” in denying Vicky’s case and granted her a new hearing.

Not long after that, a federal district court judge ordered the immigration court to schedule a bond hearing for Vicky, where “the burden is on the government to show that her continued detention is justified,” NIJC spokesperson Samantha Ruvalcaba said in an email. While the hearing has yet to be scheduled, the district court judge ordered that it must take place on or before April 5.

“If Vicky had had representation before the (immigration judge) the first time, it’s possible that we wouldn’t be here,” Drake said. “It’s possible that those due process issues wouldn’t have occurred or at least could have been found out and remedied prior to Vicky receiving a denial in her case.”

Drake said it’s much more difficult for people who are detained to fight their immigration claims. Franzblau said many of the decisions ICE makes regarding cases are discretionary with little to no explanation. The NIJC has asked ICE to release Vicky three or four times, Drake said, and ICE never gives specific reasons for why they deny her.

Having support from the NIJC has changed Vicky’s outlook for her future — she said she sees her team as “angels from God.”

“I see them this way, because, think about it — if this organization didn’t exist, if these people did not work in this field, I wouldn’t have a shred of hope,” Vicky said. “But thank God, they exist.”

For profit detention centers

The GEO Group facility in Aurora is just one of many private, for-profit immigrant detention centers in the country. Analysis from the American Civil Liberties Union found that as of July 2023, just under 91% of people held in ICE custody are in a facility run by a privately owned prison corporation.

“Now it’s a bit more difficult to get people to speak out against detention in this broader climate where under the Biden administration, they’ve drastically increased the use of immigration detention,” Franzblau said. “Even though candidate Biden promised to end private immigration detention, they’ve gone very much in the opposite direction and expanded immigration detention at really, really alarming rates.”

Since President Joe Biden took office, the number of people in ICE detention has grown from 14,000 to over 39,000 people awaiting civil immigration proceedings, Franzblau said.

Kotecki said ICE remains committed to “promoting safe, secure, humane environments for those in our custody,” and said ICE has scaled back multiple detention facilities since the start of Biden’s administration.

“We are committed to ensuring, to the extent possible, that individuals remain in a facility that is close to family, loved ones, or attorneys of record,” Kotecki said. “The agency continuously reviews and enhances civil detention operations to ensure noncitizens are treated humanely, protected from harm, provided appropriate medical and mental health care, and receive the rights and protections to which they are entitled.”

The federal government contracts with private companies like the GEO Group, which leads to a large profit — the GEO Group in 2022 made more than $1 billion from its ICE contracts alone, according to ACLU findings. Despite the large dollar amounts going to the corporations running the facilities, conditions and treatment for those detained remain subpar, critics say.

“Their failures to fulfill their duties in detaining immigrants and facilitating their participation in court is a major part of what led to the due process issues and Vicky’s case in the first place,” Drake said.

People make money off of keeping people detained, and that’s so problematic. You cannot be making money off of people wanting to seek a better life.

– Andrea Loya, executive director of Casa de Paz

Andrea Loya is the executive director of Casa de Paz, an organization that helps people released from the Aurora ICE facility transition out as they are released. She said many of the hardships people in the detention center experience are related to basic needs: Some don’t have working microwaves or shower curtains in their units, and others struggle to access the allowed quantity of undergarments.

Another one of the most common complaints Loya hears from people coming out of the Aurora facility is a lack of information, particularly when it comes to medical procedures. She said the center will release someone after they had a surgery with no follow-up care or information on what they need to do to recover.

Most of this, Loya said, is due to the privatization of these detention facilities. She said it’s difficult to keep the GEO Group accountable, because if someone brings up a concern to either ICE or the GEO Group, they just take each other’s explanation for what happened.

Kotecki said ICE generally requires a “medical intake screening” for every new arrival in their facilities within 24 hours of their arrival, as well as a “complete health assessment” within 14 days. He said for many people in ICE custody, this is “the first professional medical care they have ever received,” which can lead to the discovery of previously undiagnosed chronic health conditions.

“Facilities are further required to provide access to medical appointments and 24-hour emergency care,” Kotecki said. “Detained noncitizens have access to a continuum of health care services, including screening, prevention, health education, diagnosis, and treatment while in ICE custody.”

To Loya, privately operated immigration detention facilities simply don’t work. She said she doesn’t understand how anyone could think it’s OK to take someone who is already traumatized and seeking safety in another country and lock them up.

“People make money off of keeping people detained, and that’s so problematic,” Loya said. “You cannot be making money off of people wanting to seek a better life.”

Even on Thursday, when the Denver area was under a major winter storm warning, Loya said the facility released 10 people. She said one of the people released called and explained the conditions to his family, telling them he had his hands and feet shackled. He told his family he “was treated like I was a murderer.”

“It’s heartbreaking because you don’t understand what these people have been through in their own countries, and so you don’t understand their trauma, and then you do things like that, the treatment with the shackles.” Loya said. “These dehumanizing things that you do to people, even if they didn’t have any trauma before coming to the U.S., they absolutely have trauma now.”

People Loya sees come out of the Aurora facility have been detained anywhere from four months to several years.

Several members of Congress, including U.S. Rep. Jason Crow, a Centennial Democrat, have spoken out against using detention facilities like those run by the GEO Group.

“I’m deeply concerned by recurring reports of harassment and abuse in Aurora’s GEO detention facility,” Crow said in a statement. “I will continue to conduct oversight and fight to end for-profit detention facilities.”

Alternatives to detention

Experts with the NIJC say immigrants seeking safety in the U.S. shouldn’t be detained at all.

“In my opinion, someone coming to this country seeking protection should not be jailed for two years just because they’re trying to prove that they’re going to be tortured in their home country,” Drake said.

Franzblau said new policies to restrict the use of illegal reentry criminal charges would help many people like Vicky. Drake said someone can get that charge just for showing up at the border and asking for help after being deported. Both also agreed that mandatory detention is unnecessary, and that anyone seeking asylum or protection does not need to be detained.

“There are also multiple community-based alternatives to detention,” Drake said. “ICE has so many ways to monitor cases if they need to, but also, those alternatives in many cases are not even necessary. Especially if the applicant has counsel, the rates of attending their court hearings — which is what ICE is purportedly concerned about — are very high.”

Vicky’s circumstances would typically make her eligible for asylum, too, but because she has a criminal conviction, she is not eligible for asylum. Franzblau said these limitations on asylum create additional barriers for people who need protection.

America’s immigration system is about the luck of the draw, Loya said. Two people could cross over the border together, and she said one could end up in a shelter in Denver while another ends up detained by ICE.

“I think that times of election come around and people are so involved, they’re so interested,” Loya said about legislators. “We have to advocate all the time — we don’t have to advocate only when they’re separating kids and children… We need to keep focus, because it’s wrong all the time. It’s not just wrong when it’s convenient for an agenda.”

Drake said despite everything she’s been through, Vicky maintains a positive outlook. She always tries to help other detainees even when she’s not in the best place. Drake remembers reading through transcripts from Vicky’s earlier court proceedings, and noted her answer when a judge asked Vicky to designate a country of removal.

“She said, ‘I can’t go back to Honduras, for XYZ reasons. If you have to send me somewhere, can I go to Ukraine,’ because that was right after the war had broken out, and she wanted to help the people in Ukraine,” Drake said. “So I think that just summarizes a lot about Vicky. She’s very selfless. All she has known is trauma and hardship and an inability to be herself safely, and despite that, she is one of the most positive people, most full of light that I think I’ll ever meet.”

When she’s released, Vicky first wants to get some fried chicken from Popeyes. Then she looks forward to taking care of herself and putting effort into her hair and nails so she can feel more like herself.

“There have been times where I feel depressed or feel hopeless, but I’ve spent time reading books, especially spiritual ones because they are uplifting,” Vicky said. “I read ‘Sosegar el Alma’” — “Soothe the Soul” — “and I learned to be more positive and to believe that good things can happen.”

SUPPORT NEWS YOU TRUST.