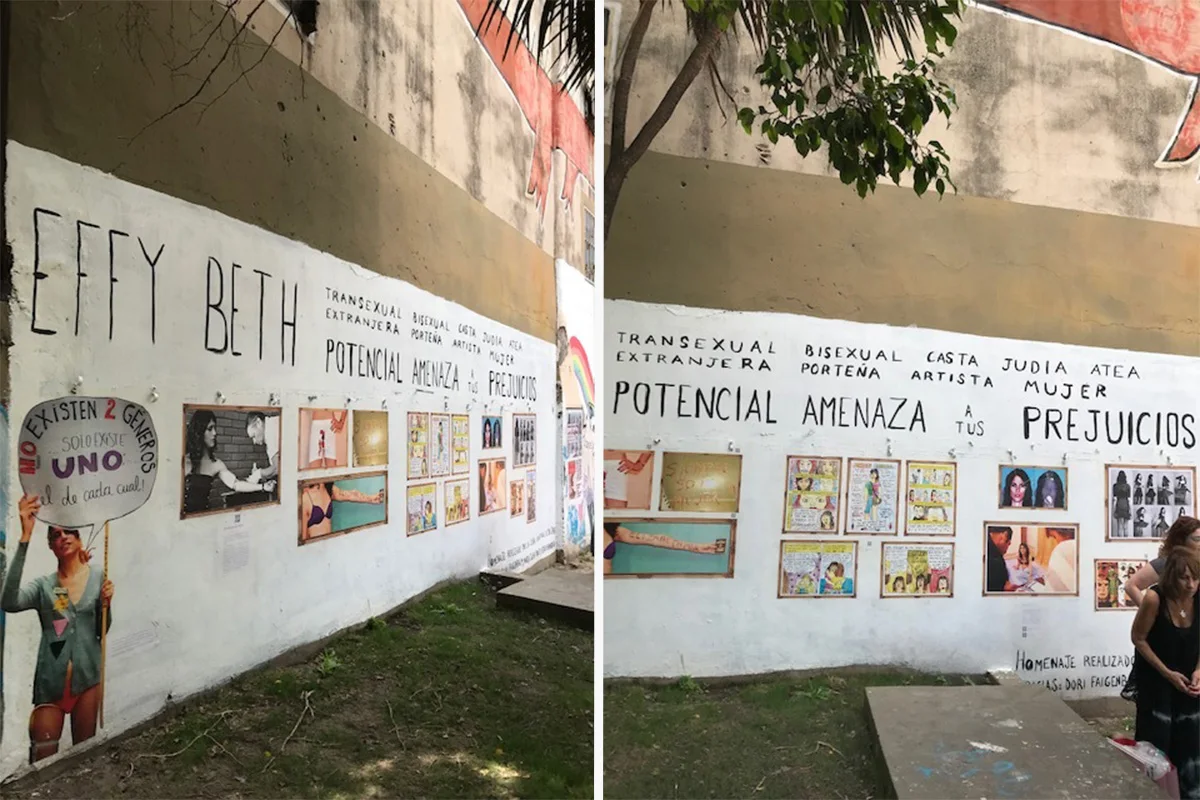

On a quiet street in Buenos Aires, tucked in the corner of a serene park with a playground, you’ll find a mural. The mural acts more like a collage, a gallery, an artist’s retrospective, a bold statement in simple black letters at the top, listing markers of the artist’s identities:

Jew. Bisexual. Trans. Atheist. Woman. Artist. Porteña (resident of Buenos Aires).

Alongside it, a promise, an artist’s manifesto and a threat: POTENCIAL AMENAZA A TUS PREJUICIOS (“Potential menace to your prejudices”).

This mural showcases the work of Elizabeth Mia Chorubczyk, aka Effy Beth, a multidisciplinary artist whose work defied categorization, including everything from cartoons to photography to high-concept and shocking performance art, and who explored themes of religion, sexuality, gender roles, Argentine society and identity, to name just a few.

“Her work was so innovative because before Effy, nobody summoned Judaism, LGBTQ+ rights, transgender people — there was nobody like her,” said María Julia Prut, a curator who continues to work with Effy’s art. “Due to this, she opened the door for other people to feel they have the right to be who they are, and they have civil rights. Besides this, I think her legacy is that everybody can do art, everybody can express herself, himself, themself. She always said that everybody breathes the same air so we are all the same.”

Effy Beth died by suicide in March of 2014 at the age of 25. A decade later, her work continues to influence queer, trans, Jewish and feminist communities in Argentina, and many porteñes, including her mother, Dori Faigenbaum, are working to keep her legacy alive.

“Her legacy is super important because there are a lot of Jewish people making art, but there are no other Jewish people who, being who they are within the collective, who do so much for the LGTBIQ+ community, and so much for feminism,” said Melodía Mej, a member of Judíes Feministas, a collective for feminist, lesbian and nonbinary Jews in Buenos Aires. “There is a void there that does not become such because both Dori and Julia, her curator, continue that work.”

In one of her most iconic photographs, “Una nueva artista necesita usar el baño” (“A new artist needs to use the bathroom”), Effy stands with her back turned, about to enter the women’s restroom. She is topless, and on her back are the names of the many women artists she admired and sought to emulate: Cindy Sherman, Judy Chicago, Marina Abramovic, Barbara Kruger.

In another photo, called “Mi disfraz” (“My disguise”), Effy stares intensely into the camera, wearing masculine clothes and a chest binder, her hair pulled back. “It forces you to not look away,” Faigenbaum said.

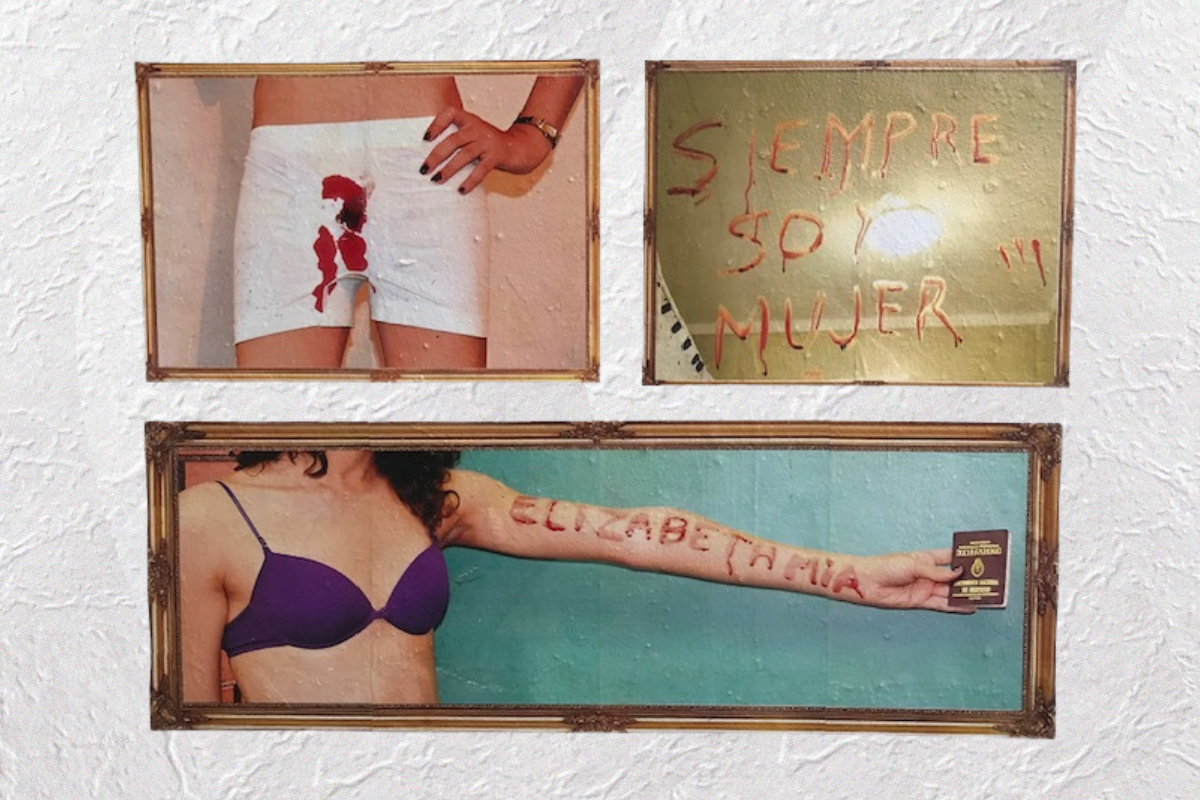

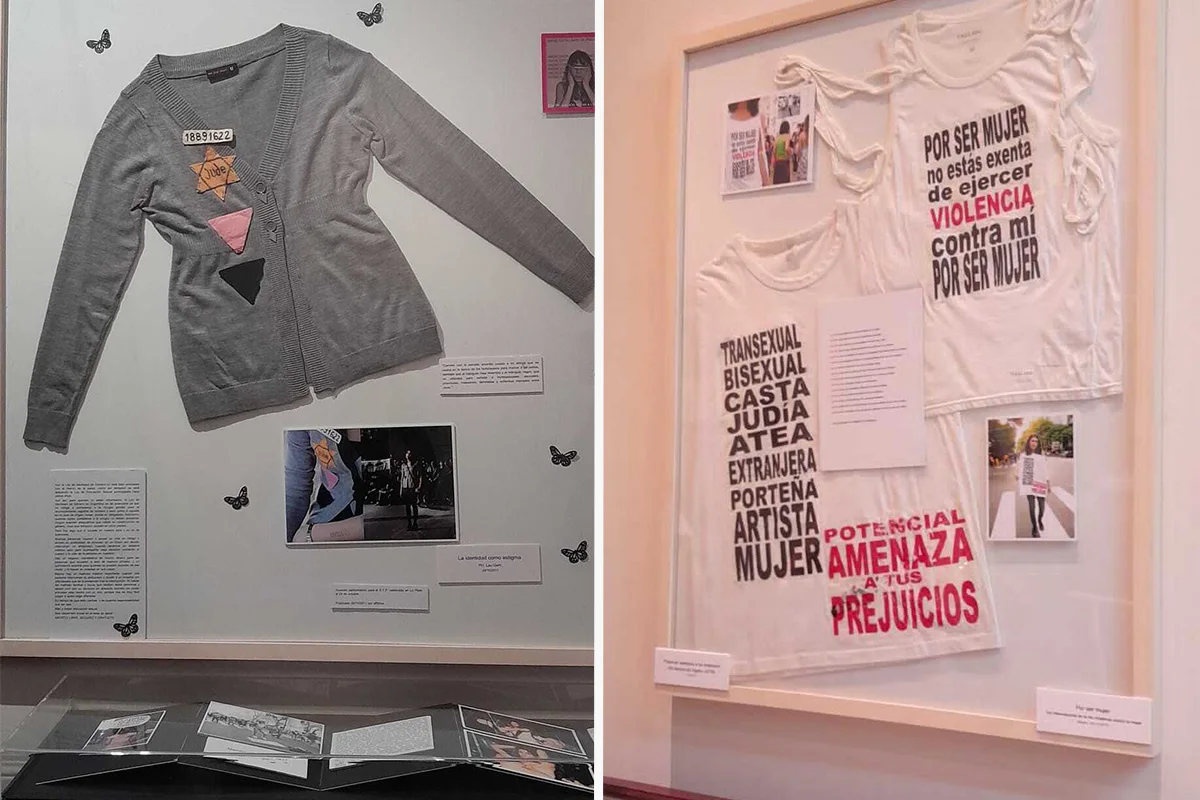

Her Judaism and dual national identity – Effy was born in Israel and lived there until the onset of the Gulf War — underpins much of her work, including a photo where she compares the ways in which her identity is listed on her Israeli and Argentine passports (the former as male, the latter as female), connecting the discrepancy in her passports to skewer the antisemitic trope of the “Wandering Jew.” In another set of photos, Effy wears a gray cardigan embroidered with markers associated with identification, discrimination and persecution during the Holocaust, and markers of identities she shares — the yellow star, the pink triangle.

“She felt so close to the Jewish community, to Judaism,” Faigenbaum said. “She wasn’t allowed to express her identity inside the community at that time. But that was a search for her, because she wanted to have this space, because she wanted to be welcomed inside a community.”

Mej said that it is important to Jewish feminists in Argentina that Effy’s story is shared beyond their circles, and that she would like to see more content about Jews like Effy being taught in madrijim groups (mentorship and education programs for Jewish teens), for example. She hopes that Effy can serve as a reminder and conduit for Jewish spaces to be more open and inclusive, a reminder that queerness and transness and Judaism are not separate entities.

One area of Effy’s art that is perhaps most resonant in her legacy are her provocative performance pieces. In one performance, called “Identity,” Effy gathered many people in the flat she shared with her mother and took them into the bathroom with the lights off. Then Effy put eyeliner and makeup on guests’ faces in the dark and put them in one dress that had been an object of tension in the family, as it was the first dress she wore to a gathering on New Year’s Eve, creating conflict with some family members who were not accepting of her transition.

“I traveled to Miami and she was acquiring some art books and shoes and clothes for Effy,” Faigenbaum said. “Meanwhile, [Effy] filled the flat with people to do the performance without telling me at all. This was something that occurred very often.”

There was one rabbi in Buenos Aires who welcomed her at his table with his family and community for Passover, Rosh Hashanah and other observances. “That’s why it’s so important, Effy’s work, because she wears her Judaism like a flag in times that were so difficult for her because she was rejected,” Prut said. “This identity for her was so important, to fight this rejection.”

One of Effy’s performances took place at Prut’s home, where the artist filled her kitchen with a ton of balloons, to symbolize the way she felt out of oxygen in society because of prejudice.

Many of Effy’s performances centered on subverting or investigating touchstones of Argentine society and culture. Once, on World AIDS Day, Effy organized a demonstration where people donned t-shirts identifying them as HIV-positive, and had them offer mate, a traditional infused herbal drink and an essential touchstone of Argentine culture, to passersby, to illustrate the stigma that still existed around the virus. A favorite of Faigenbaum’s was a soccer tournament Effy organized called “Football for Equality,” where participants all had to play in high heels, a subversion of gender roles in the soccer-obsessed country.

Effy used this often provocative, occasionally shocking performance art to speak on issues important to Argentine feminists, including safe, secure and free abortion, an end to gender-based violence, and a number of LGBTQI issues. Among two that stood out to Mej were Nunca Serás Mujer (“You Will Never Be A Woman”), where Effy would have blood drawn every month to represent her menstruation, and Córtala (“Cut It”), an in-your-face examination of individual and societal “trans panic” involving her walking around in a corset with her genitals visible and a giant scissors.

“Everything that had to do with identity, and the concept of judgment, she played with them a lot,” Mej said. “She had a lot of humor in these graphic displays. That’s where she shared a little more of herself. The rest was more provocative and more politically incorrect. You saw that people were very dumbfounded because, well, the idea was to go break in and raise awareness.”

The consensus among those who knew her: Effy was not interested in “art for art’s sake,” but sought to make art that questioned oneself and one’s perspective. “There’s a phrase I love from Effy because it’s so great and defines so many things,” Prut said. “She said, ‘Art makes you think. If art doesn’t make you think or trouble you, it’s useless. Art is not just a garnish to decorate your home. The art must make you think. The art must fight the things that are unfair in the world.’”

Although March 2024 marked the 10th anniversary of Effy’s passing, Faigenbaum said it was only recently, about three years ago, that people and institutions began reaching out to her about sharing Effy’s work and her story. More recently, she said organizations like Judios Argentinos Gays (JAG) have connected with her.

Faigenbaum is also working to pay Effy’s legacy forward. In addition to preserving her daughter’s artwork and hoping to translate Effy’s work into English, she is working on establishing a foundation to support and sustain up-and-coming trans artists like Effy.

“We don’t want more transgender artists walking alone, fighting with the system with no support or guidance or companion, many things that Effy needed in the past,” Faigenbaum said. “We are doing a lot for Effy’s work, but we are aware we can do that because she’s not here, and that’s horrible. If she were alive, we could not do all the things we are doing. We want to break this pattern and help new transgender artists to be able to show their work to the world without prejudice.”

And it is through that work, through the telling, that Effy continues to live. “A legacy sometimes sounds like something from someone who is no longer here and has already stopped,” Mej said. “What Dori does is keep Effy moving, and I think that’s what communities need.”

As for Faigenbaum, when asked about her relationship with Effy, about her legacy, she will often say, “I was just her mom,” to reinforce that Effy is the artist and activist in the family. But in the repetition, there is something else — a reminder that loving and celebrating and carrying the banner for your trans child can be as simple as a reflexive response, and should be easy as breathing.

“I’m proud and I feel full of love, and I am grateful to have had her for 25 years, and for her being an extraordinary person,” Faigenbaum said. “I learned so much from Effy. Many people loved her.”