Authored by Dr Hane Maung for GenderGP.

Background

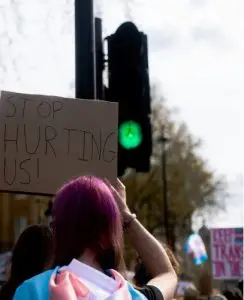

Over the past decade, the United Kingdom has become an increasingly hostile place for trans people, especially for trans youth (Hines, 2020; Horton, 2024; McLean, 2021). In addition to vilification by the mainstream media and attempts by politicians to curb the rights of trans people, gender affirming healthcare for trans youth has been severely restricted. In the context of this hostile political environment, NHS England commissioned an independent review into gender affirming healthcare services for trans youth, led by Dr Hilary Cass. On 10th April 2024, the Cass Review published its Independent Review of Gender Identity Services for Children and Young People: Final Report. This present article shows that many of the claims and recommendations of the Cass Review are inaccurate, empirically unsupported, ethically unacceptable, and grounded in prejudice.

“Through its cisheteronormative agenda, the Cass Review is enacting the prejudice that trans people suffer in the United Kingdom”

The Evidence Base

At the outset, it is important to note that the Cass Review did not produce any new data. Rather, it reviewed data from previous studies on the effects of gender affirming medical treatment for trans youth.

However, review of the literature was profoundly inadequate. Notably, the Cass Review dismisses a very large number of studies and omits studies from the past two years. Hence, it neglects a vast amount of evidence on the benefits of gender affirming medical treatment for trans youth in its analysis.

The reason for dismissing this evidence is that it did not come from randomised controlled trials. However, this indicates a serious misunderstanding of the roles and limitations of randomised controlled trials compared with other sources of evidence.

For many medical interventions, including gender affirming medical treatment for trans youth, randomised controlled trials are unfeasible and unethical, because the consequences of not intervening would be very apparent to the participants and also would be unacceptably harmful (Ashley et al., 2023). Accordingly, evidence from randomised controlled trials is often not required of many medical interventions, including abortion, appendicectomy for acute appendicitis, aortic aneurysm repair, and so on (Worrall, 2008). Indeed, the assumption that randomised controlled trials represent the “gold standard” in evidence-based medicine has been criticised for neglecting other important sources of evidence (Anjum and Mumford 2017; Deaton and Cartwright 2018; Grossman and Mackenzie 2005).

When randomised controlled trials are unfeasible or unethical, other forms of evidence are used to inform clinical decisions. Generally, the assessment of a causal relation between a healthcare intervention and a clinical outcome require: (1) evidence of a statistically significant association between the intervention and the outcome; and (2) evidence of a mechanism linking the intervention and the outcome (Russo and Williamson, 2007). These forms of evidence are precisely what are provided by the numerous studies on the effects of gender affirming medical treatment for the health and wellbeing of trans youth, which the Cass Review dismissed.

Some of these studies used matched control groups and large sample sizes, which enabled the demonstration of a statistically significant association between gender affirming medical treatment and improved health in trans youth (Green et al., 2022; Tordoff et al., 2022; Turban et al., 2020). Other studies found evidence of social, psychological, and biological mechanisms through which gender affirming hormone treatment decreases depression and anxiety in trans youth (Chen et al., 2023; Grannis et al., 2021). Numerous other studies corroborate the findings that puberty suppression and hormone replacement therapy are associated with improved mental health and social wellbeing in trans youth (Allen et al., 2019; de Vries et al., 2014; Kuper et al., 2020; van der Miesen et al., 2020).

And so, there is ample statistical evidence and mechanistic evidence that gender affirming medical treatment results in health benefits for trans youth. By dismissing this evidence because it did not come from randomised controlled trials, the Cass Review is holding gender affirming medical treatment to an unreasonable and unethical standard that is not required of many other healthcare interventions (Maung, 2024).

Especially concerning is the way in which the Cass Review minimises the contribution of untreated gender dysphoria to the increased risk of suicide in trans youth:

“Tragically deaths by suicide in trans people of all ages continue to be above the national average, but there is no evidence that gender-affirmative treatments reduce this. Such evidence as is available suggests that these deaths are related to a range of other complex psychosocial factors and to mental illness.” (p. 195)

The suggestion that “there is no evidence that gender-affirmative treatments reduce [deaths by suicide in trans people]” is false. As noted above, numerous studies with large sample sizes and comparison groups provide ample evidence that gender affirming medical treatment leads to decreased suicidality in trans youth (Allen et al., 2019; Green et al., 2022; Turban et al., 2020). For example, in a recent study, trans adolescents who had gender affirming hormone treatment delayed until they were older were shown to suffer from significantly higher rates of depression and suicidality than trans adolescents who received gender affirming hormone treatment promptly (Sorbara et al., 2020). Furthermore, there is evidence that lack of access to gender affirming medical treatment is associated with increased rates of mental illness and suicidality (Tan et al., 2023; Tordoff et al., 2022).

The extenuating claim that suicide in trans youth is “related to a range of other complex psychosocial factors and to mental illness” is a vacuous statement. Suicide is widely understood to be a complex multifaceted behaviour and there are always multiple social, psychological, and contextual factors involved in its causation (Maung, 2020). Recognising this multifactorial complexity does not preclude us from acknowledging that untreated gender dysphoria is one of the factors that contributes to suicide in trans youth and, moreover, that it is a factor that can be effectively alleviated with gender affirming medical treatment.

Dismissing such a vast quantity number of studies on the basis of an unreasonable and unethical standard amounts to flagrant evidence denial that could cause significant harms to trans youth. Moreover, the double standard the Cass Review imposes between gender affirming healthcare and other forms of healthcare, which is highly suggestive of motivated reasoning.

Social Transition

Further to dismissing the vast amount of evidence on the benefits of gender affirming medical treatment, the Cass Review also dismisses a lot of important evidence on the benefits of social transition:

“The information above demonstrates that there is no clear evidence that social transition in childhood has positive or negative mental health outcomes. There is relatively weak evidence for any effect in adolescence.” (p. 164)

The suggestion that there is “no clear evidence” for the mental health benefits of social transition is false (Turban, 2017).

Studies have yielded evidence that trans youth who had socially transitioned exhibited levels of mental health and social wellbeing comparable to their cis peers (Durwood et al., 2017; Olson et al., 2016). Moreover, the levels of mental health and social wellbeing among trans youth who had socially transitioned were much higher than the levels of mental health and social wellbeing among trans youth in previous studies who had not socially transitioned (Aitken et al., 2016; Balleur-van Rijn et al., 2013).

The above findings are also corroborated by qualitative studies which have examined the benefits of social transition for trans youth and their families (Horton, 2023; Kuvalanka et al., 2014).

As well as dismissing relevant evidence, the Cass Review goes on to make claims and recommendations that are not informed by any evidence at all (Kennedy, 2024). For example:

“However, sex of rearing seems to have some influence on eventual gender outcome, and it is possible that social transition in childhood may change the trajectory of gender identity development for children with early gender incongruence.” (p. 164)

As with all aspects of our characters, it is likely that gender identity is a contingent outcome of complex and dynamic interactions between social, physiological, psychological, and biographical factors throughout development. The Cass Review seems to acknowledge this complexity. However, the claim that “social transition in childhood may change the trajectory of gender identity development” is totally conjectural and empirically unsupported.

The above passage also reveals a false assumption underlying the Cass Review’s proposal to limit social transition. This is the assumption that gender identity’s being in part socially influenced makes it less legitimate or less valuable. However, this is mistaken. As social beings, effectively all of our values, desires, and dispositions are partly influenced by the social environments wherein we are embedded. What is important is not what caused these values, desires, and dispositions, but whether we endorse these values, desires, and dispositions as authentic features of our characters. The fact that gender identity is in part socially influenced does not make it any less authentic.

Indeed, there is clear evidence that trans adolescents do endorse their gender identities as authentic features of their characters. Research has shown that gender identity in trans youth is remarkably stable and that the regret rate for gender affirming healthcare is very low (Brik et al., 2020; Cohen-Kettenis and van Goozen, 1997; de Vries et al., 2011; Olson et al., 2022; van der Loos et al., 2022). Furthermore, a recent study showed trans youth who sought gender affirming healthcare demonstrated the relevant understandings and capacities to examine and endorse their own identities (Clark and Virani, 2021).

Remarkably, the Cass Review itself cites an NHS audit of trans youth registered at the Gender Identity Development Service, which found an extremely low rate of retransition:

“Of the 3,499 patients audited, 3,306 were included within the analysis. … <10 patients detransitioned back to their [birth-registered] gender …” (p. 168)

The fact that fewer than 10 of the 3,306 people included the audit retransitioned to their genders assigned at birth indicates that gender identity is very stable in this group, which undermines the Cass Review’s concern about gender identity being fickle in adolescence. To be clear, it is important to acknowledge that some people do retransition and that these people ought to receive supportive care. However, the fact that a very small proportion of people do retransition is insufficient to justify withholding gender affirming medical treatment from the overwhelmingly large proportion of people who do continue to identify as trans.

The Cass Review makes the following recommendation regarding social transition:

“When families/carers are making decisions about social transition of pre-pubertal children, services should ensure that they can be seen as early as possible by a clinical professional with relevant experience.” (p. 165)

The recommendation to bring social transition within the purview of clinical opinion, rather than respecting it as a personal decision, amounts to serious medical overreach that goes against the World Health Organization’s (2019) recognition that gender incongruence is not a disorder. By making clinicians the arbiters of people’s identities and behaviours, it violates people’s freedoms and their rights to autonomy, privacy, and self-determination. Furthermore, it potentially enables harmful conversion therapy practices (Kennedy, 2024).

Prejudice

This brings us to a worrying assumption underpinning the aims of the Cass Review:

“Taking account of all of the above issues, a follow-through service continuing up to age 25 would remove the need for transition at this vulnerable time and benefit both this younger population and the adult population.” (p. 224, emphasis added)

This passage reveals the cisheteronormative agenda motivating the Cass Review. The desired outcome, “remove the need for transition”, indicates the assumption that being trans is something wrong that would be better to fix. Here, the implications are that cisgender lives are judged to be more valuable or desirable than transgender lives and that healthcare services should prioritise encouraging youth to assume cisgender lives, regardless of the suffering that this causes (Horton, 2024).

Through its cisheteronormative agenda, the Cass Review is enacting the prejudice that trans people suffer in the United Kingdom. Instead of acknowledging and respecting trans identities as being legitimate and valuable identities in their own rights, it presupposes that cisgender outcomes are preferable to transgender outcomes and uses this to recommend the withholding of gender affirming medical treatment from trans youth.

This prejudice manifests in two further features of the Cass Review. First, the recommendations of the Cass Review would impose even more obstacles to access to gender affirming medical treatment for trans people aged under 25, which amounts to a double standard between treatment for trans people and treatment for cis people. Cis people are not required to endure these obstacles when they seek interventions that aim to align their bodies to their gendered goals, such as testosterone for cis men diagnosed with hypogonadism, cis women who seek breast augmentation or reduction surgery, and puberty blockers for children who are deemed to be undergoing precocious puberty. To require trans people to endure these obstacles comprises an injustice.

Second, the Cass Review excluded any involvement from trans people, whether they are clinicians, academics, or service users (Kennedy, 2024). This is a serious omission, as it neglects the important viewpoints of people who have experienced the challenges of navigating a healthcare system that is set up for cis people. By including only cis people in the process, the Cass Review only serves to reinforce the cisheteronormative bias that permeates the healthcare system in the United Kingdom, rather than attending to the needs and values of trans community.

(Further compounding the prejudice, the Cass Review uncritically cites the work of an academic who ran a Twitter account to make transphobic comments and harass trans people online.)

“The Cass Review is a profoundly flawed document that could result in significant harms to trans youth and young trans adults if its recommendations are implemented…”

Other Inconsistencies and Inaccuracies

Inconsistent Scope

The website for the Cass Review states:

“The scope of the Review is to consider NHS models of care for children and young people, so NHS and privately provided gender services for adults — that is, those who are 18 or over — are outside our remit.”

However, this is contradicted by the Cass Review’s recommendation that:

“NHS England should establish follow through services for 17–25-year-olds at each of the Regional Centres …” (p. 42)

Aside from neglecting the mathematical fact that 25-year-olds are aged over 18, the focus on age 25 is concerning, because it suggests a plan to impose further obstacles to access to gender affirming medical treatment for trans adults as well as for trans youth. Again, this would comprise a serious injustice that violates trans people’s rights to determine their own identities and attain their embodiment goals.

Brain Development

In order to defend the focus on age 25, the Cass Review suggests:

“It used to be thought that brain maturation finished in adolescence, but it is now understood that this remodelling continues into the mid-20s as different parts become more interconnected and specialised.” (p. 102)

It is a common misconception that the brain stops developing in the mid-20s (Somerville, 2016). Indeed, the brain continues to develop throughout the lifespan, forming and updating neural connections as the person learns new things and encounters different environments. Moreover, the fact that the brain is developing throughout adolescence does not imply that it does not have the sufficient capacity during adolescence to enable one to understand, appreciate, and endorse one’s gender identity. As noted above, there is clear evidence that trans youth do have the relevant understandings and capacities to examine and endorse their own identities (Clark and Virani, 2021).

Nonbinary Identities

In the foreword, Dr Hilary Cass states:

“Secondly, medication is binary, but the fastest growing group identifying under the trans umbrella is non-binary, and we know even less about the outcomes for this group. (p. 15)”

This is a baffling claim and it is far from clear what is meant by the phrase “medication is binary”. If the claim is that gender affirming medical treatment is only capable of affirming binary (transmasculine or transfeminine) transgender identities, then the claim is plainly false. Gender affirming treatment regimes can and have been tailored to affirm nonbinary identities. These include regimes for androgynous hormone treatment, microdosing, and selective oestrogen receptor modulators, which are tailored for nonbinary people who do not want to achieve full feminisation or full masculinisation (Cocchetti et al., 2020; Hodax and DiVall, 2023; Xu et al., 2021).

Historical Inaccuracy

The Cass Review claims:

“For many centuries transgender people have been predominantly trans females, commonly presenting in adulthood.” (p. 114)

No citation is provided for this claim, perhaps because there is no evidence for it. The claim is not only unverifiable, but is contradicted by the evidence that is available regarding the numerous people throughout history who would today be classified as transmasculine (Riverdale, 2012). The above claim also ignores the numerous historical and contemporary reports of transmasculine people across different cultures, including North America, Japan, East Africa, and China (Katz, 1976; Wieringa, 2007; Shaw, 2005; Zhu, 2015).

This may seem like a pedantic point to make, but it is relevant because it highlights the disregard for evidence and accuracy that seems to pervade the entire Cass Review. No attempt has been made to understand the history, culture, or values of the people about whom the review is supposed to be, which indicates a lack of credibility or seriousness.

Language

The Cass Review suggests:

During the lifetime of the Review, the term trans has moved from being a quite narrow definition to being applied as an umbrella term to a broader spectrum of gender diversity. (p. 187)

This is plainly false. The term “trans” has long been used to encompass a diverse spectrum of identities, including transmasculine, transfeminine, nonbinary, and genderqueer identities, among others. See, for example, the definition of the term in the National Centre for Transgender Equality’s Frequently Asked Questions About Transgender People from 2016, which predates the launch of the Cass Review in 2020 by four years. The failure of the Cass Review to note this indicates ignorance and a lack of any serious attempt to understand the history, language, and culture of the trans community.

Data on Referrals

“Figure 2: Sex ratio in children and adolescents referred to GIDS in the UK (2009-16)” of the Cass Review is misleading. The way the graph is presented makes it look like the number of referrals to the Gender Identity Development Service per year have been increasing exponentially since 2009. This is to support the narrative that more and more children are being made by social pressure to think they are trans.

However, the graph arbitrarily stops at 2016. If the graph had continued to 2020 when the Cass Review was commissioned, then it would have shown that referrals per year reached a plateau after 2016 and did not show any significant increases between 2017 and 2020 (Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust, 2020). Furthermore, the lower number of referrals per year before 2016 could have indicated that fewer people were being referred than ought to have been referred. The number of referrals per year is an unreliable indicator of the number of trans youth there actually are in the population.

Conclusion

The Cass Review is a profoundly flawed document that could result in significant harms to trans youth and young trans adults if its recommendations are implemented. Not only does it engage in flagrant evidence denial, but it makes several inaccurate claims and recommendations that are not supported by any evidence at all. Moreover, its openly cisheteronormative agenda, whereby cisgender identities are judged to be more desirable or legitimate than transgender identities, enacts the prejudice that is suffered by the trans community in the United Kingdom. It is our position that the Cass Review is an unethical and unscientific document that serves to legitimise a system that commits sustained injustices and harms to the trans community.

Further Reading:

A Response to NHS England’s Ban on Puberty Blockers for Trans Youth

Learn more about Transgender Healthcare on our Knowledge Base brain after the mid-20s.