All trans candidates are now obligated by the 1995 laws to include a list of their deceased names on their petitions.

A transgender candidate was eliminated from the ballot in Ohio because she did not include her past name under a rarely used, decades-old law. According to reports first reported by local journalist Morgan Trau of Ohio, Vanessa Joy was informed on Wednesday that the Stark County Election Commission had rejected her application to run for office despite receiving enough signatures to do so. If the name change occurred within the previous five years, the law requires any prospect running for office to list it on their application.

This law, which appears to have been selectively enforced against Joy, could impact at least two additional trans candidates.

Any candidate who has “a change of name within five years preceding” filing for office is required by the 1995 law to list their previous name on the voting application. As a result, all transgender applicants are compelled to include their deadname on their petitions, which is the name they generally drop when they transition. For various reasons, including name changes brought on by marriage, this condition is waived. For trans people, there are no such exceptions.

Joy was successful in securing enough petitions to run for office in Stark County’s House District 50. She was set to automatically become the party’s candidate in the district since she had no primary rival. After the preceding legislator, Representative Reggie Stoltzfus, announced a run for Congress, leaving the position unoccupied, she was scheduled to run against Matthew Kishman. Now that her petition was rejected, she is unable to work as a write-in candidate in the district because Ohio law forbids candidates with barred petitions from running in writing campaigns.

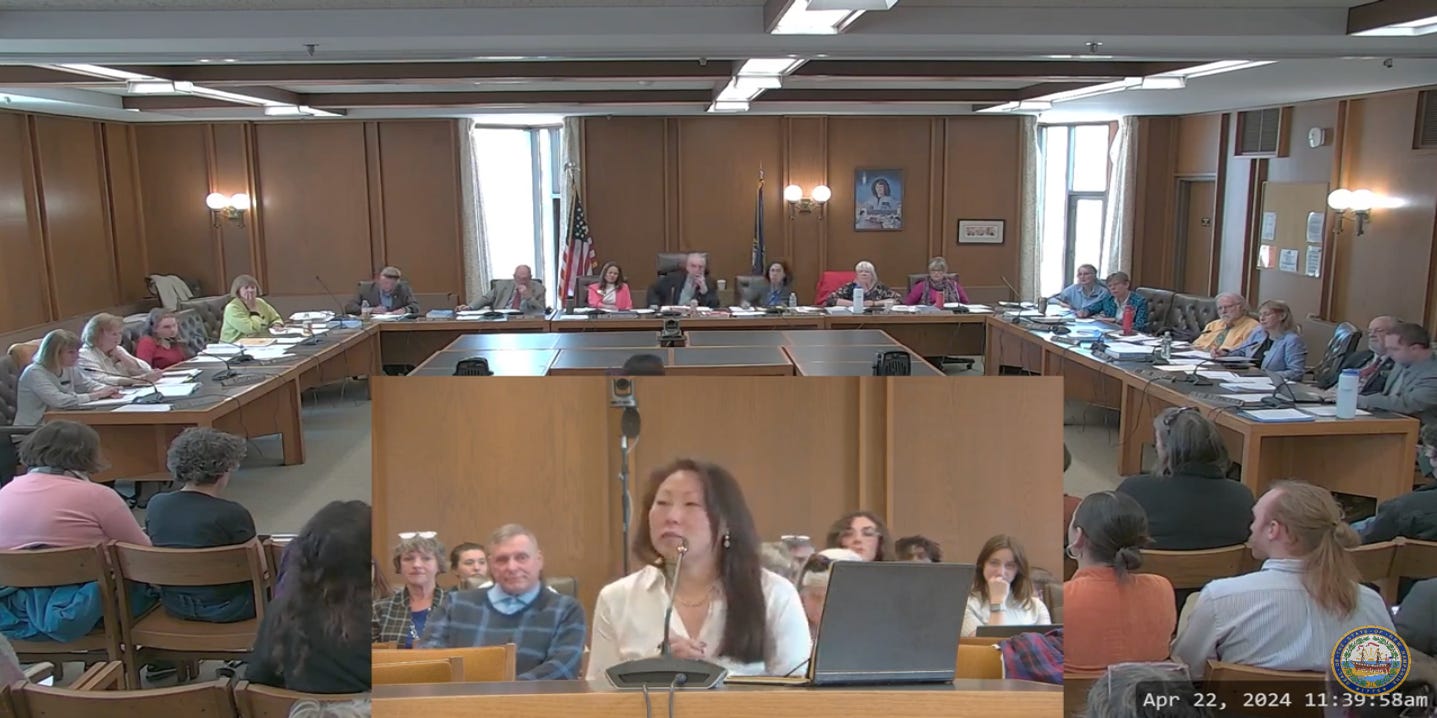

When questioned about the choice, Joy responds to Erin In The Morning by saying there was no info that a prior name was necessary. The need is not listed in the 33-page secretary of state candidacy guide, nor is it mentioned on the Stark County site. Additionally, there is no room on the election application form for listing an old name. Joy provided duplicates of her form, demonstrating that, as you can see here, there is no space or indication for listing an old title:

When questioned about the decision made by the local county fee, Vanessa Joy responds that she is “one of the first, if not the only, people that this regulation has been applied to in Ohio.”

Other transgender individuals do not seem to have had their candidacies disqualified by the law; instead, it appears that Joy’s law was selectively enforced against her. The Republican Party of Ohio may use this against transgender individuals across the state, though it is unclear whether action may be taken against those individuals after their applications have been accepted.

This problem might not only occur in Ohio. Although it doesn’t seem to be the case in most states, at least one other state has a similar filing requirement. A clause in Michigan’s election legislation mandates that name changes must be made public within ten years. The requirements for people changing their name as a result of marriage are also waived by Michigan rules:

Joy responds, “I’m also looking into options, but my hope is that I can find legal representation to challenge the language of this regulation and make it more inclusive to transgender folks,” when asked about her next steps. Marriage-related name changes and those who have already informed voters of the name change on prior petitions are now exempt from the law.