This study aimed to characterize how medical schools in Chile integrate curricular content on LGBTIQ + health issues into their programs. Our focus encompassed both the pre-internship (first five years) and internship stages (final two years), which collectively form the mandatory training pathway for obtaining the M.D. degree in Chile. Unlike in many countries, Chilean medical schools oversee content in both stages, providing a unique perspective on the complete medical curriculum.

Presence of LGBTIQ + content and hours of dedication

We found that 78.6% of medical schools reported teaching some related content. This percentage is above what was previously reported by other studies; for instance, only 27.5% of Japanese medical schools reported teaching some of these topics [15], which could be explained by contextual factors such as strong cultural taboos around sexuality and intimacy in Asia [23].

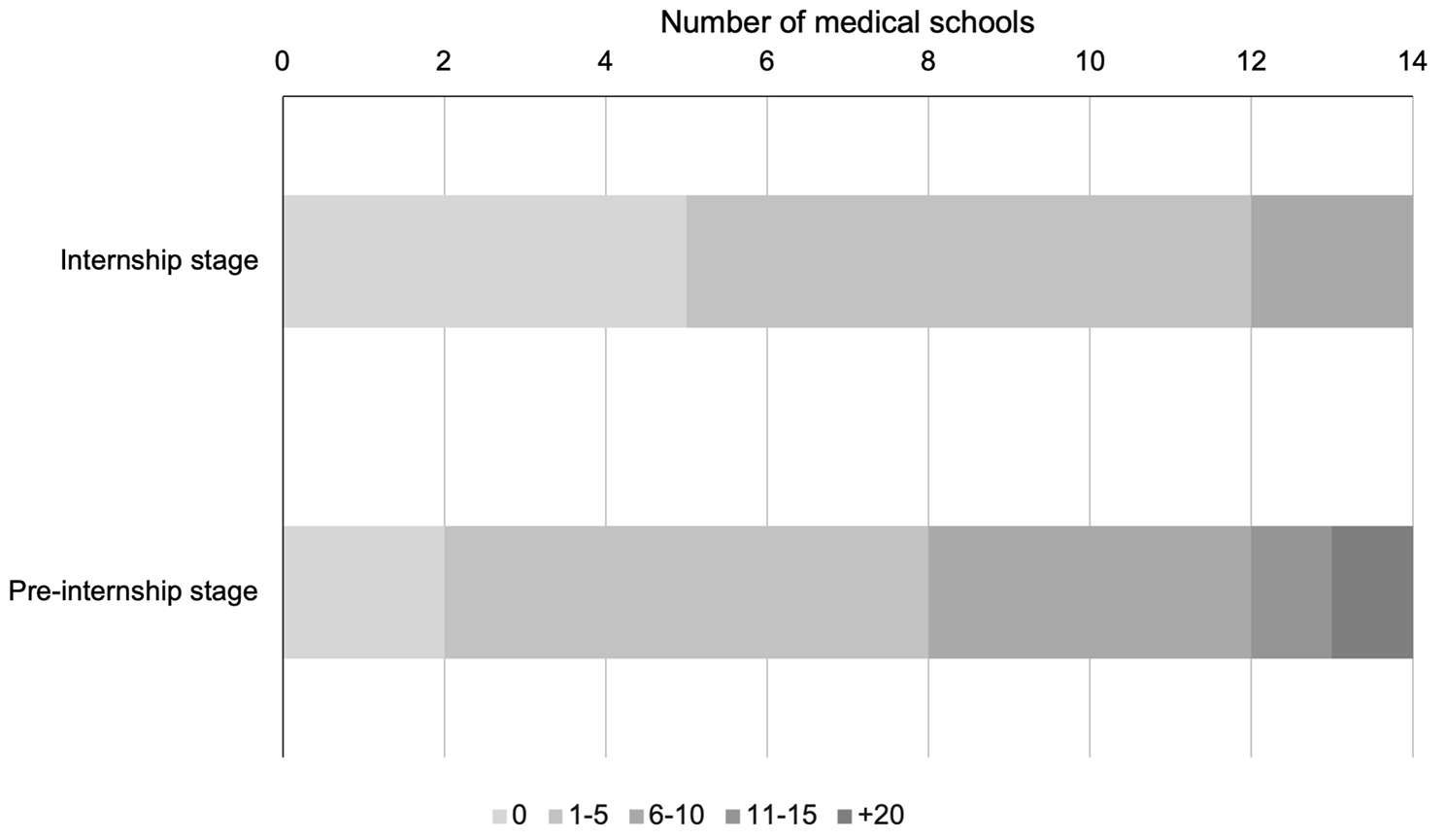

In Chile, the range of time allocated to LGBTIQ + training in medical programs predominantly fell between 1 and 5 h, both in pre-internship and internship stages. Specifically, during pre-internship, two medical schools reported no hours allocated for this training, and one school indicated over 20 h, while at the internship stage, five medical schools reported no hours dedicated to this training. This contrasts with findings from similar studies elsewhere: in the US and Canada a median of five hours was reported [13], while a study in the UK reported a median of 11 h [17]. Despite Chilean medical schools dedicating time to LGBTIQ + issues, the hours reported did not reach the minimum of 35 h considered necessary to achieve LGBTIQ + cultural competence in medical students, a standard that also includes interacting with at least 35 LGBTIQ + patients during their training [24].

LGBTIQ + content present in medical training

The topics mainly corresponded to HIV from a biomedical perspective, other sexually transmitted infections (not HIV), and sexual orientation, while other topics such as non-binary identities, partner violence, or body image in the LGBTIQ + populations were among the least taught topics. These data highlight the need for a shift towards a more holistic approach to LGBTIQ + health medical education, moving beyond a strictly biomedical focus to include social determinants of health, as underscored in Cooper, Chacko, and Christner’s study on integrating LGBT health into medical curricula through the lens of social determinants [25].

The topics related to the trans population were among the least addressed by Chilean medical schools, including sex-reassignment surgery, gender identity, and transitioning. The deficit in this type of content has been previously reported. For example, a quarter of the students reported not feeling prepared to discuss gender reassignment surgery or gender transitioning, while 80% felt prepared to discuss HIV with their patients, according to a survey of 4,262 medical students from 170 schools in the United States and Canada [9]. Likewise, medical students have reported feeling less competent and comfortable treating transgender patients than lesbian, gay, and bisexual patients [26, 27]. Moreover, as medical students in the UK advance in their training, they become more confident in discussing with patients their sexual orientation, but not their gender identity [28].

Transgender patients experience discrimination from health professionals, decreasing their use of and access to these services [29]. Specifically, they reported being called by wrong names, being consulted about inappropriate topics, having their concerns dismissed, being insulted, ridiculed, being denied health care, and even feeling that they needed to educate the health professionals who cared for them [30, 31]. In addition, they experienced worse outcomes in their health care compared to their cisgender peers with higher rates of cancer, higher cardiovascular risk, higher presence of chronic diseases, sexually transmitted infections, substance use, and mental health conditions [31, 32]. Medical schools should make specific efforts around health for the transgender population. Biases present in basic science training, the production of biomedical knowledge, and the understanding of the categories of sex and gender as uncomplicated topics have been detected [33].

LGBTIQ + health at different life cycle stages emerged as an issue when asking about content not present in the survey. In the US, it was estimated that by 2030 the LGBT populations over 65 years of age could even double its number, reaching 6 million [34, 35]. LGB patients have a higher risk of disability, poorer mental health, a higher prevalence of smoking, and higher alcohol consumption than their heterosexual peers [36]. Elderly lesbian patients are less likely to access preventive screening with mammography, and trans patients, as they age, are more likely to have health problems related to their biological sex, which provides a stressor by having diseases of a sex with which they do not identify [37]. Therefore, medical schools must integrate LGBTIQ + content into their courses and internships dealing with geriatric patients.

Curricular modifications

In this study, 71.5% of the medical schools believed that the content delivered regarding LGBTIQ + was moderately insufficient or insufficient. Identifying knowledge gaps regarding LGBTIQ + health content in undergraduate medical training is relevant since it has been shown that curricular modifications effectively increase medical students’ knowledge of LGBT health issues [38]. On the one hand, integrating the LGBTQ curriculum and patient exposure may reduce the risk of adverse health outcomes within this community [39]. On the other hand, literature has reported that medical students perceived insufficient curricular coverage of LGBTIQ + health issues, heterosexist assumptions in the curriculum, and even transphobic content in classes [40]. The curricular level’s limitations included the lack of an integrated curriculum and competent academics regarding these topics [28, 41].

In improving teaching content, it is important to incorporate the recommendations of LGBTIQ + community members into guidelines for working with LGBTIQ + patients [42]. Although curricular inclusions and modifications at the undergraduate level are essential, it is also necessary for medical schools to provide continuing medical education opportunities to current physicians to ensure that they all have the basic knowledge and skills since a lack of knowledge and competence has been demonstrated in these topics [43].

Extracurricular modifications and the hidden curriculum

This study detected the presence of LGBTIQ + content in Chilean medical schools; however, it is essential to note that extracurricular measures related to the hidden curriculum impact doctors’ competence in these issues. What students acquire outside the classroom will be transferred to their formal education, and therefore it is relevant that the presence of these issues transcends university life [44].

The guidelines of the Association of American Medical Colleges for implementing curricular and institutional changes to improve the health of the LGBTIQ + populations indicate that it is crucial to establish environments in which reflection is promoted, research is carried out, and the complexity regarding gender and sexuality is understood [45]. The efforts made at the institutional culture level and in promoting respect and diversity have shown improved health students’ attitudes towards LGBTIQ + patients [46]. Additionally, clinical educators must understand the impact they make through their role models and seek to deliver training and care without prejudice [47, 48]. Finally, medical school administrators and faculty can contribute by creating an identity-affirming environment that not only helps LGBTIQ + students feel more included, but also extends this inclusivity to LGBTIQ + faculty and university employees, thereby reducing implicit biases among all members of the academic community, including those not part of sexual minorities [49,50,51].

Methodologies of teaching and learning

The primary methodologies used by Chilean medical schools corresponded to lectures (92.8%), clinical cases (42.9%), and clinical simulation (28.6%). These findings align with what Obedin-Maliver et al. reported, where the principal methodology used in medical schools in the United States and Canada was lecturing (59.8%) [13]. Numerous methods are reported in the literature, including presentations, interview sessions, group work, panel discussions with LGBTIQ + populations, peer-to-peer learning, forums, and the use of virtual material [43].

Exposing students to LGBTIQ + patients can increase their comfort level in caring for these individuals [24], and Solotke et al. have recommended including LGBTIQ + topics in medical schools [52]. Similarly, medical students believe it would be beneficial to address LGBTIQ + issues in communication training sessions and through activities that directly involve LGBT patients [28]. Several studies have integrated direct interactions between medical students and LGBTIQ + patients, from panel discussions in pre-clinical courses [53, 54] to clinical clerkships at LGBT health centers [55]. However, Mains-Mason et al.‘s systematic review, which concentrated on studies assessing knowledge retention and/or clinical skills acquisition in medical trainees, revealed a significant gap in clinical skills development, particularly in real patient interactions. Despite improvements in knowledge retention, their review found that most curricula primarily utilized lectures or online modules, with minimal emphasis on interactive scenarios for enhancing communication skills with LGBTIQ + patients. This highlights the critical need for more practical, patient-centric experiences in medical education to effectively bolster both theoretical knowledge and clinical skill sets [56].

Regarding simulated patients, in the United States and Canada, there is an increase in the use of this methodology to represent LGBTIQ + patients and increase the exposure of students. However, there is no consensus on who should perform sexual minority patients [57].

Strengths and limitations

A major strength of this study is that it is the first at the Latin American level to characterize the teaching of curricular content associated with the LGBTIQ + populations. In addition, it provides a validated instrument for measuring LGBTIQ + health topics and the current level of coverage in the context of Chilean medical schools. On the other hand, the survey was answered by the medical school directors or their delegates, who had the most detailed knowledge regarding the curriculum of the medical program at their school.

Within the limitations, for ethical reasons (i.e., guaranteeing anonymity in the participation in the context of a low number of participants), it was not possible to include segmentation variables about the participating medical schools; therefore, characterizing responders and non-responders was not feasible. Moreover, the subjects might have felt pressured to give socially desirable answers despite being an anonymous questionnaire. Finally, the response rate was 58.3%, so the sample might not represent all Chilean medical schools.

Recommendations

This study revealed that Chilean medical schools used limited hours in teaching LGBTIQ + health content, especially in the internship stage of training. In addition, the topics taught were often restricted. Based on our findings and discussion, we suggest the following recommendations: