Ask 13-year-old Rebecca about her family, the Tillisons, and she’ll sum them up in a word: “chaotic.” Earlier this year, Rebecca Tillison and her family moved from Dallas, Texas to a suburb 30 minutes outside Seattle. Inside their new house, two energetic golden retrievers race across the kitchen, an orange tabby cat named Phoebe climbs across the table, Rebecca’s older brother wanders in and out of the room looking for an ice cream scoop.

Moving can bring out the chaos for any family, but for Rebecca’s parents, Mitch and Tiffany, the decision to uproot their family to Washington wasn’t really a choice.

“This is what Texas is telling us to do,” says Tiffany Tillison, Rebecca’s mom. “They basically say the state would be better if you weren’t in it.”

Rebecca is trans and, over the last six years, as the Texas legislature introduced an increasing number of bills which would limited LGBTQ+ rights, the Tillisons saw the possibility of a full life in Texas shrinking before them.

As they gather around the kitchen table, Mitch pulls out a puzzle for Rebecca to fidget with. “I’m not even going to try to solve that,” she says, giving him a look. “It’s like 300 pieces.” Unbothered, Mitch dumps the puzzle onto the table and begins to talk about the move while he hunts for corner pieces.

In 2023, 583 anti-trans bills have been proposed across the United States, and 84 of them have been signed into law. This legislation has created a stark divide for trans youth and families. About 35 percent of trans youth in America currently live in the 22 states where gender-affirming medical care is banned, according to the Williams Institute at UCLA School of Law.

The Tillison family is one of many whose lawmakers have put them in the position of choosing between bodily autonomy and home. Nearly one in 10 transgender adults—including people 18-24—have moved to avoid anti-trans policies. Many more people living in states where anti-trans bills have passed are considering moving—43 percent of transgender adults and 41 percent of young adults ages 18–24 have said they have considered moving. For families like the Tillisons, Washington state has become a place of refuge.

To protect Rebecca’s privacy, she’s going by a pseudonym in this story and Seattle Met is not directly naming where her family lives.

Washington as a Safe State

This year, Washington signed five bills into law intended to directly support trans people in the state.

Washington requires health insurance to cover gender-affirming medical care and prohibits discriminating against any LGBTQ+ person based on their gender expression or identity, among other protections. And this year, the state passed the SHIELD law which aims to protect anyone who seeks refuge in Washington or comes here for medical care from being extradited to other states that may be pursuing legal charges or investigating them. Washington also protects health care information from subpoena and records requests.

“Seattle is tremendously protective of trans youth,” says Erin Reed, a journalist and activist who focuses on anti-trans legislation. “And one of the things that makes Seattle a very attractive place is that it has one of the highest densities of transgender hormone therapy clinics in the nation.”

This level of protection and access is only available to those who can afford it. The overall cost of living in Seattle is 50 percent higher than the average, according to the 2022 Cost of Living Index published by the Center for Regional Economic Competitiveness, a nonprofit research and policy organization. And finding a home in Washington can be a challenge. The state is already struggling to keep up with housing demand.

“Some people might not get to move to Seattle, but might move to Washington, knowing full well that there are areas in Washington where the cost of living is cheaper, but also knowing that they tend to be a little bit more transphobic,” Reed said.

Though conservative state lawmakers proposed three anti-trans bills during the 2023 legislative session in Washington, none moved out of committee.

Before the Move

When asked about their life in Texas, Tiffany Tillison says “we were just a normal family.”

“But by night, there were vigilantes,” jokes Rebecca, referring to the constant feeling of being under threat as people around them pushed anti-trans rhetoric.

“I mean you’re not entirely wrong,” Mitch says with a somber smile.

“When she came out, there was a little bit of anxiety,” Tiffany says. “And then, of course, when the school board elections started happening…”

This is how most Tillison stories about Texas begin. Things were normal, then a school board election happened, or a senate bill was introduced, or the governor was reelected. Even the story of Rebecca’s coming out at age 11 is couched within the timeline of the legislative cycle.

“She came out in November of 2021,” Tiffany said. “So, she came out right as the legislation was in a lull.”

Rebecca and Tiffany were driving back from a late night soccer tournament. Rebecca had been talking in a steady stream for long enough that Tiffany was only half listening.

“I was like, Do you ever feel like you would be the opposite gender?” Rebecca said. “And then I was like, Sometimes I feel like that.”

Tiffany says that question snapped her back to attention. When they got home, she asked Rebecca if she could include Mitch in the conversation.

“I completely forgot that I told her about it until she brought me back into the living room,” Rebecca says. “She was like, ‘Let’s elaborate more on what you said.’”

“We asked, What do you picture in the future? What do you look like in the future?” Tiffany turns to Rebecca. “And you were like, ‘I have long hair and I’m wearing a ball gown.’ And then you told us you also wanted fishnet stockings and high-heeled boots. And I was like, Well, you’re 11, so let’s ratchet it down a little bit. What can we start with today? So we settled on fingernail polish.”

Rebecca chose white-ish pink. “Pink was always my favorite color,” she says.

And life could have continued that way: trying out nail polish and new names, starting the early stages of social transition. But Texas legislation was rapidly constricting their options and the temperature of transphobia around them continued to rise.

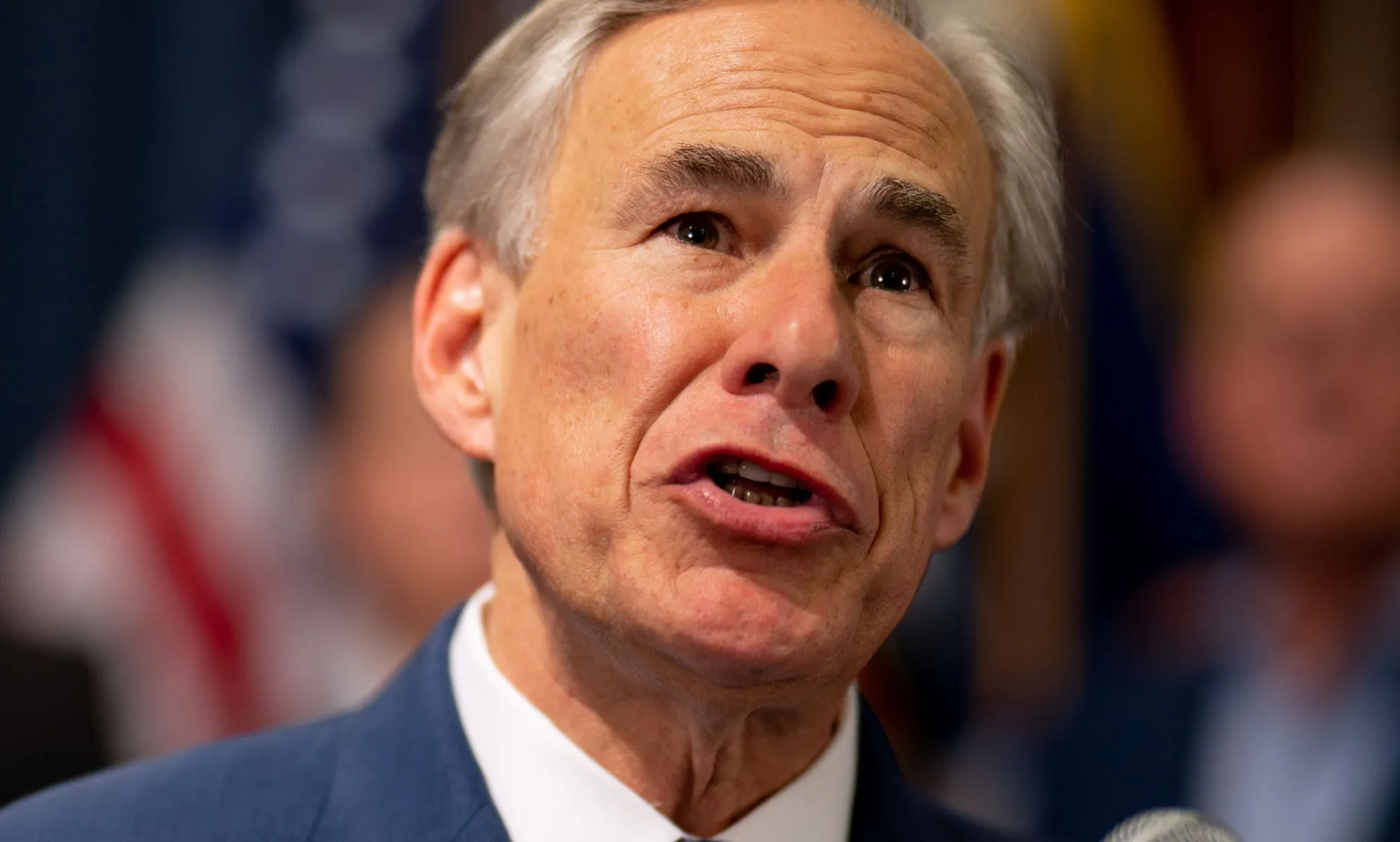

In 2022, attorney general Ken Paxton and governor Greg Abbott issued directives to the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services to investigate the parents and families of trans youth who were providing gender-affirming care, calling it child abuse. With Gov. Abbott’s re-election, the Tillisons worried their family could be investigated and potentially separated simply for supporting their daughter.

“We’re not going to have that normal life anymore, as much as we want it,” Tiffany remembers thinking. “Normal now means questioning everybody and everything. Normal started looking like isolation.”

Despite the risk, Mitch took an active role in advocating for trans rights. He spoke at school board meetings and attended protests in Austin at the rotunda building.

“We’re not moving unless we have literally done everything. There can be nothing left in the tank,” Mitch recalls saying to Tiffany.

Once, Rebecca asked to come with him to a protest, and he agreed. “We wanted her to see people fighting for her,” he says.

There were many reasons to stay. Their son had his football team. Tiffany had just started a career-defining project at work. Rebecca’s childhood best friends, the twins, lived nearby. Mitch, a teacher, didn’t want to leave his students behind. Their whole lives were there.

Then at the start of 2023, following Gov. Abbott’s reelection, Senate Bill 14 was introduced, which would ban gender-affirming medical care for trans minors, including puberty blockers and hormones, and revoke the medical licenses of any doctors who offered this care.

As the bill made its way through the legislature, doctors began to close their practices or leave the state. Many doctors also stopped taking new patients in anticipation of the bill’s passage, and with less access to affirming care the Tillisons felt like they were constantly looking over their shoulders. Anyone with access to their daughter’s medical records could report them—something as small as the name on Rebecca’s medical records not matching the name they called her could pose a risk.

“It’s wild when you start down this path, like, how you have to run everybody through a filter,” Tiffany says. “So it was like, okay, does anybody know a trans-friendly dentist? Does anybody know a trans-friendly eye doctor?”

When the bill was passed it became clear they couldn’t put off the move any longer.

“It was a life-or-death decision, like we stay behind and she potentially does not get to be who she’s supposed to be and we could lose her,” Tiffany says.

Deciding on Washington

Tiffany and Mitch began compiling a list of states where they could safely move. Colorado and Minnesota were their first choices— due to proximity to family— but Washington also ranked near the top. Tiffany said she and Mitch spent a lot of time consulting Erin Reed’s trans legislative risk assessment maps to rule out states that were at risk of passing similar legislation in the next two years. Reed has heard from many families in similar positions.

“I started to get letters and emails and direct messages about two years ago, when the first wave of medical bans were going through,” says Reed.

As these messages poured in, Reed started compiling information about which states were safe and which were not. She said this led her to create risk maps for youth and adults. Her goal was to present people with the information they needed to make informed choices.

“Not everybody wants to move. Many people can’t move for various reasons, be it money, be it custody situations— where there’s a custodial agreement in place where one parent cannot leave the area,” Reed says. “It’s hard for people to get up and just leave their jobs. And so there are a lot of people that cannot.”

The Tillisons saw this play out in real time. “There was a group of us that were all talking about leaving at the same time,” Tiffany recalls. “And then one by one, they were getting shut down for various reasons.”

Tiffany is a civil engineer and Mitch is a teacher. As the family’s primary income provider, the decision of where to land rested with Tiffany.

“I’d like to say there was something magical about Washington, but y’all just needed engineers,” she says.

The Tillisons estimated spending about $20,000 on the move all in. They borrowed money from friends and family, cashed in retirement plans and maxed out credit cards to make it possible. And they also recognize how impossible that kind of expense would be for many families.

“When you’re already living paycheck to paycheck, you know, how do you make that move?” Tiffany said. “Trans kids are from impoverished families. They’re from middle-class families. They’re from all walks of life.”

Even for trans people already living in Washington state, legal protection does not always mean equal access to services. The Tillisons acknowledge that some of that safety comes not just from legislative and cultural support, but also from being a white family in a majority-white city.

“Washington state is trying to build out a sanctuary for trans communities,” says Jaelynn Scott, the executive director of the Lavender Rights Project, which provides legal and social services to the Black intersex and gender diverse community. “But I don’t think that we have yet figured out how to actually do that in a way that is inclusive of the needs of BIPOC queer and trans people.”

Washington’s protections make the state attractive to those who can afford to move here, but many trans and queer people who already live in Washington still need further protection and support, says Scott.

“Trans communities of color, especially Black trans communities, have never had the level of access to gender affirming care that other communities have had in this country. That includes Washington state,” Scott said. “And that is because of economic disparities, employment, true access to full health insurance coverage, and leisure time or time to take off to actually get any affirming surgeries and medical care that they need.”

To ensure full and equitable access to gender affirming care, Scott says Washington should invest in “guaranteed income for all, full housing access for trans people, legislation that ensures that discrimination against trans people in housing cannot happen, appropriations bills that support the capacity of BIPOC led organizations to provide care for folks, and wraparound services for people who seek refuge here, either from other states or from out of the country, who are also queer and trans.”

Reed sees these kinds of services as necessary for Washington to support what she calls “an internal displaced refugee crisis.”

“We are going to start seeing more unhoused LGBTQ+ people, especially trans people, as people are fleeing states, as people just get up and leave. Even if they have no financial plan and they have no financial resources, it’s become untenable to stay where they are,” Reed says.

Trans people, and trans people of color especially, are already overrepresented in Washington’s homeless population, as well as nationally. A 2022 survey from the Trevor Project found among people ages 13 to 24, 38 percent of transgender girls and women, 39 percent of transgender boys and men, and 35 percent of nonbinary people reported experiencing homelessness or housing instability at some point in their lives.

“At the end of the day, a lot of these people just need their medication, and they’re willing to make this move if they can do it, just to get their medication,” Reed says. “I know people that have moved to other states that are living out of vans. They made that calculus: it is better for me to live out of a van in Massachusetts than it is for me to live in Texas and potentially have my kid taken away from me just because they’re trans.”

For a family like the Tillisons, who could afford to make this move, it was the right call.

“Just to get her the health care she desperately needed in Texas was awful— the battles that we had to go through,” Tiffany says of Rebecca. “Here, it was one phone call. Everything was approved by insurance. ‘Great. Here’s your appointment. We’ll see you then.’ Why is it not that easy for everybody else?”

Settling In

With their family housed and beginning school in Washington, Tiffany and Mitch are trying to stop looking over their shoulders. But now other feelings have started to surface.

“I’m not going to lie, there’s a lot of anger. There’s a lot of moments where I sit here and I think, Why the f*** could Texas not get their s*** together? Why did I have to move 2,000 miles away?” Tiffany says.

For the Tillisons there’s a kind of survivor’s guilt too. They are still in touch with the families they organized alongside in Texas, many of whom have not been able to leave. And while getting access to affirming doctors, teachers, and therapists has been much easier, finding a community in the Seattle area has been more difficult.

“There’s not as much need here for daily support in that way,” Tiffany says. “Here you can go to your pediatrician and say, My kid has come out, what are the next steps? And you don’t have to worry that you’re going to leave the office and that physician is going to call CPS. You can go to the school and say, Okay, my child has come out, they now need to use a different bathroom. And the school’s gonna go, OK, great. Thanks for letting us know.”

Despite feeling less connected to community, Mitch says he can see the difference in Rebecca’s everyday life.

“It’s not just us making her feel safe. It’s everything here making her feel safe. The constant signage, the constant allyship, the never seeing another person being harassed for it,” he says.

Though they’re still getting their legs under them in Washington— their car still has Texas plates —Mitch has already taken Rebecca on a few trips into Seattle. The cats at Twice Sold Tales in Capitol Hill made a big impression, and so did all of the pride flags.

When asked about what she likes about living in Washington, Rebecca gives the most teenage answer possible. “There’s only six periods and school ends at like 2:35,” she says with a sly smile.

But then she goes to grab her favorite shoes from the other room and holds them out, “The inside of the shoes, on the right side of your foot, it’s the pride flag, and on the left side it’s the trans flag.” Rebecca says in Texas she would have been bullied for wearing them to school, but here “I actually have gotten a lot of compliments about them.”

She’s joined a club at school supporting LGBTQ+ students and allies, and is slowly making new friends. Though she’s careful to clarify, “I’m the type of person who doesn’t consider people a friend unless they straight up tell me that they’re my friend.”

She says she’s started sitting with a student who had a rumor spread about him last year “that he smelled really bad.” When someone at school tried to bully him again Rebecca stepped in. “And then he made fun of my glasses, but we don’t talk about that,” she laughs.

“Who doesn’t get bullied in middle school, right?” Tiffany adds with a smile. “Light bullying is the best you can ask for when you’re in seventh grade. For [Rebecca] to come home and just be good, to be just a regular teenage girl, for me, that was everything I could have asked for.”