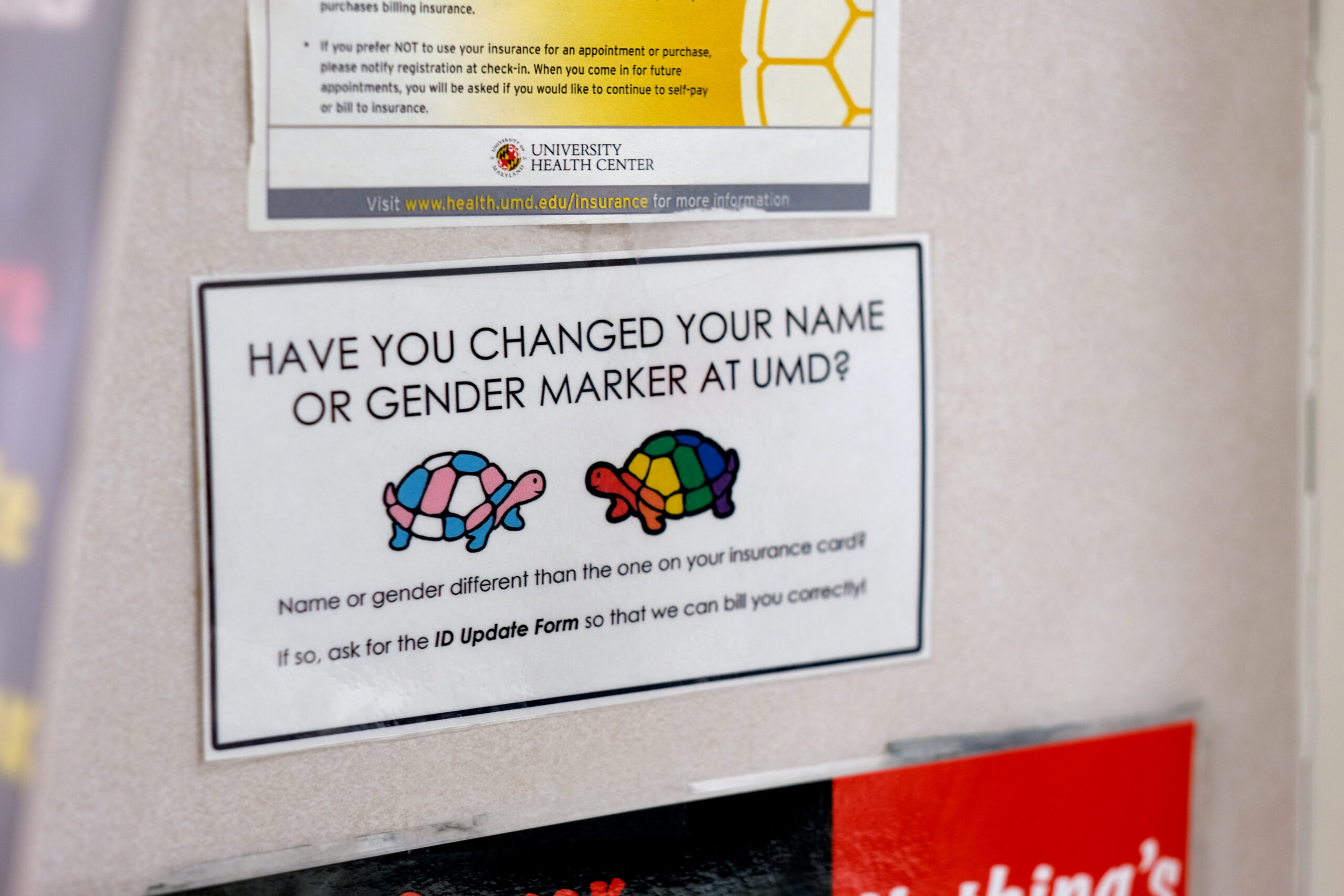

Individuals are reminded to release their name and sex symbol in the school’s program by a banner at the University of Maryland Health Center in College Park. Photos by Tommy Tucker from the Capital News Service.

Written by Tommy Tucker

Paisley Parsons has been transitioning to gender-affirming medicine for ten years, and he has spent the majority of that time in Maryland finding a reputable health team.

Perkins’ access to nearby treatment when beginning his transition was constrained because he was from near Hagerstown. The District of Columbia, Baltimore, or Philadelphia were the best places for him to get what he needed.

“Finding a team of doctors that I felt was up to par took me perhaps six or seven years, but before that, finding somebody educated and skilled was hard to come by,” according to Parsons. “The majority of the doctors in my immediate vicinity simply had no knowledge of anything trans-related, and much of it was a contact issue.”

Maryland also has varied access to gender-affirming care, despite improvements since Parsons began his transition. Trans care may entail a lot of work on the patient’s part, from finding knowledgeable doctors to having access to prescribed hormones.

A medically important part of treatments known as gender-affirming treatment includes hormone therapy, speech changes, light treatment, and surgeries. However, using the patient’s preferred pronouns and staying current on gender identities and techniques are also part of health “care.”

According to Dr. Helene Hedian, the clinical knowledge director at Baltimore’s Johns Hopkins Center for Transgender and Gender Expansive Health, some of my clients travel long distances to see me. In the past year, there has been an increase in demand for providers, which has occasionally resulted in lengthy wait times.

In cities like D.C. and Baltimore, there is a concentration of licensed physicians, with less accessibility the further away a person is from the big city. Hedian asserts that Maryland is not an exception to regional bureaucracy of care, especially for physicians who offer hormones and surgical procedures.

The Hopkins Center is working to address the regional centralization problem by offering training to practitioners outside of Baltimore, but it continues to be a problem everywhere, according to Hedian.

Hedian advises browsing the service directory on the website of GLMA: Health Professionals Advancing LGBTQ Equality if you’re looking for a doctor with experience providing gender-affirming treatment.

The number of doctors in metropolitan areas is confirmed by the file. For instance, a search for testosterone treatments in Easton that affirms gender reveals that Baltimore, D.C., is more than an hour away. C. Alternatively, Odenton.

According to Lee Blinder, executive director of Trans Maryland, a trans-led group organization, Baltimore City is likely the closest to the transgender community in terms of access, but the wait times are extremely long for our knowledgeable providers. “Many people in our more remote areas of the state, or even in some of our counties, are unable to obtain an accepting provider,” according to the report.

Trans Maryland, formerly known as Trans Healthcare MD, was founded by Blinder as a group tool for connecting transgender and non-binary citizens to certified professionals.

According to Blinder, “Trans Maryland began as a result of my and our other co-founders’ lack of access to gender-affirming care.” “Looking at the national environment, we are incredibly fortunate to be based in Maryland.”

This time, in May, Gov. Wes Moore (D) signed the Trans Health Equity Act, mandating that Medicaid and the state’s medical assistance program increase coverage for gender-affirming care starting January 1, 2024. In June, Moore also signed an executive order shielding Maryland residents who seek gender-affirming treatment from legal repercussions from different states.

According to Hedian, “Those two incidents in the past year have increased the demand for gender-affirming treatment in Maryland.” “People are moving into the state, particularly because they aren’t able to get the care they need in many states.”

According to a study by the Williams Institute on Medicaid insurance for gender-affirming treatment, 24,000 trans people live in Maryland as of 2022, with an estimated 6,000 of them enrolled in Medicaid.

According to the Maryland Department of Health, the number of Medicaid enrollees seeking gender-affirming care under the policy will rise from 98 in 2022 to about 25 per month.

Although there are no numbers for 2023, providers have seen a significant increase in the past month.

Moore told the Capital News Service, “We’re aware of the problem and we know that being able to address health care shortages (is) something that has long been standing within the state.” “We want to make sure that our state is welcoming, and I also know that things like the Trans Health Equity Act were done in the right way.”

Moore stated that having the health resources and staff to treat patients is a top priority and that there are shortages in various clinical fields as well.

In order to meet the demand

, Dr. Julius Joi Johnson-Weaver, a board-certified family doctor, provides gender-affirming treatment through a program at their private practice. Johnson-Weaver, who is transgender and non-binary, has dealt with a lot of their clients’ problems with care access.

“When someone is ready to transition ‘in whatever way it usually starts to feel immediate,’ it causes a lot of anxiety,” according to Johnson-Weaver, and they are then informed, “Oh yeah, it’s going to be six months, you know, or it will take some time to get an appointment.”

They discovered that Johnson-Weaver frequently had to teach doctors on fundamental concepts related to their treatment at the beginning of their health transition. Office workers and doctors would frequently misgender them, which made the entire process more stressful. Trans people frequently experience this.

According to a study conducted by the University of Michigan and Michigan State University Schools of Social Work, transgender people who must inform health professionals about transgender issues are more likely to experience sadness, anxiety, or depressive feelings. Additionally, the study discovered that more than a third of transgender and non-binary people felt disrespected by medical professionals.

“I’m frequently unable to obtain an accepting experience because I see specialists as a non-binary trans person,” according to Blinder. “I’m giving information, sometimes essentially, about what non-binary means and what it means for me as a person in this care,” she said.

Trans people who reside in major cities now have an easier time finding a skilled physician. Trans/non-binary resident of Baltimore City Kerrigan Dougherty had little trouble finding qualified care; he first visited Chase Brexton before switching to Hopkins.

Dougherty remarked, “I’ve had a generally positive experience receiving primary care.” “I’ve found my health care to be fairly satisfactory.”

But, Dougherty encounters problems when pharmacies fail to fill prescriptions.

According to Dougherty, the pharmacy is a constant source of stress and the bane of my life. “It doesn’t make sense to me because they can see in my chart that the prescription has been sent.” “Sometimes it’s that my prescription is rejected, and other times it is that they say they have the prescription.”

Problems with transgender people’s pharmacies are caused by a number of factors. For starters, claims that are denied frequently result from the plan classification of a patient’s identity.

According to Richard DeBenedetto, an associate professor at the University of Maryland Eastern Shore and a doctor who specializes in HIV and transgender care, if the insurer determines that the customer is classified as female, the prescription for testosterone may be automatically denied.

“Some of the issues with trying to get people who are transgender their medications have to do with structural issues,” according to DeBenedetto. “Even though that is silly, there are problems with how individuals are coded on their driver’s licenses and insurances, and fixing them requires a legitimate formalities that can sometimes take years.”

Problems with fulfillment are also exacerbated by continuous drug shortages. The injectable variations of both estrogen and testosterone have been in short supply, according to the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, in recent months.

The amount of testosterone that pharmaceutical companies can produce and the amount that pharmacies get are both restricted by the Drug Enforcement Administration.

“Based on the controlled substance regulations, one company is not just able to produce more because there is a need, because another company cannot,” according to DeBenedetto. “You know, it’s been challenging to provide people with hormones for their medications, and you’re sort of hopping from one to the other in an effort to make it work.”

DeBenedetto said it is challenging to pinpoint what needs to be addressed, whether it be suppliers, policy, or health care systems as a whole.

“We will continue to encounter problems unless we make choices that are obviously ideal,” according to DeBenedetto. “We see a lot of transphobia, and we’re going to keep developing systems that categorize people as other until we can truly have people seen as people who aren’t any different from anyone else.”

Del. The Trans Health Equity Act was co-sponsored by House Health and Government Operations Committee Vice-Chair Bonnie Cullison (D-Montgomery). She claimed to be aware of the access problems and to collaborate attentively with Trans Maryland to address them. She added that she concurred with Moore that the bill was the best course of action to safeguard Marylanders’ access to healthcare.

“Trans Maryland provided amazingly supportive assistance in the bill’s documentation and in responding to inquiries from colleagues,” according to Cullison.

Cullison urges trans residents to get in touch with her about these problems by saying, “Talk to us, keep us informed.” “Let us know what we can do in terms of advocacy or policy.”