Between 28 February and 1 March 2021, I sent the following text as an email attachment to around 30 people I considered my closest friends. The subject line was: “A bombshell.” I smirked at the unintentional pun and wondered whether anyone else would. It was simply titled: “Lucy.”

The dam burst on 16 February, when I downloaded FaceApp, for a laugh. I had tried the application a few years earlier, but something had gone wrong and it had returned a badly botched image. But I had a new phone, and I was curious. The gender‐swapping feature was the whole point for me, and the first picture I passed through it was the one I had tried before. This time it gave me a full‐face portrait of a woman in midlife: strong, healthy, clean‐living. She also had lovely flowing chestnut hair and a very subtle makeup job. And her face was mine. No question about it – nose, mouth, eyes, brow, chin. She was me. When I saw her, I felt something liquefy in the core of my body. I trembled from my shoulders to my crotch. I guessed that I had at last met my reckoning.

Very soon I was feeding every portrait and snapshot and ID‐card picture I possessed of myself into the magic gender portal. The first archival picture I tried, contemporaneous with my first memory of staring into a mirror and arranging my hair and expression to look like a girl, was an anxious, awkward studio portrait of a tween. The transformed result was a revelation: a happy little girl. Apart from her long black hair, very little had been done to transform Luc into Lucy; the biggest difference was how much more relaxed she looked.

And so it generally went – I was having a much better time as a girl in that parallel life. I passed every era through the machine, experiencing one shock of recognition after another: that’s exactly who I would have been. The app weirdly seemed to guess what my hairstyle and fashion choices would have been in those years. And the less altered the images were, the deeper they plunged a dagger into my heart. That could have been me! Fifty years were under water, and I’d never get them back.

My high school graduation portrait became an impossibly delicate almond‐eyed fawn (age 17 was indeed the summit of my beauty, which is probably why my male incubus immediately grew a beard). Ten or 12 years later (there are regrettably few photos of me in my 20s; I’ve always been camera-shy), I am a Lower East Side post-punk radical lesbian feminist with a Dutch‐boy bob and a pout. Here I am at a Sports Illustrated junket in Arizona, age 33, looking demure in a white sweater over a red polka‐dot dress.

There are many reasons why I repressed my lifelong desire to be a woman. It was, first of all, impossible. My parents would have called a priest and had me committed to some monastery. And the culture was far from prepared, of course. I knew about Christine Jorgensen [the first person widely known in the US for having gender reassignment therapy] when I was fairly young, but she seemed to be an isolated case. Mostly, what you came across were vile jokes from Las Vegas comedians and the occasional titillating tabloid story. I kept searching for images or stories of girls like me, without much luck.

Over the years I consumed an impressive amount of material on transgender matters, from clinical studies to personal accounts to journalistic exposés to porn. Not much of the porn, though; it grossed me out. I researched the subject as deeply as I did any of my books, but my notes all had to be kept in my head.

I immediately disposed of all materials, because I was terrified of being seen. Until browsers made anonymous searching possible, I wiped the search memory on my computer every day. Why, you may ask, did I feel it necessary to go to such lengths? The short answer is because my mother regularly raided my room, reading anything in my handwriting and vetting all printed matter for anything that might even remotely allude to sex. I extended that caution to my friends, most of whom would surely have been sympathetic, because of the notion I long possessed that women would be disgusted and repelled by my transgender identity. Where did I get that one? It may be because until I was in my late teens I didn’t know many women, as an only child of isolated immigrants, and I didn’t have a female friend until I was 17.

Needless to say, I was awful at sex. I did not know how to act like a man in bed. I wanted to see myself as a woman in the act of love, but I also had to repress the desire, while simultaneously trying earnestly to please my partner (because I almost never slept with anyone I didn’t love, at least at first).

I was not at all attracted to men, and I spent enough time in gay environs in the 70s to be sure of that. At puberty and afterwards I was uncertain how to construct a masculine identity. I hated sports and dick jokes and beer‐chugging and the way men talked about women; my idea of hell was an evening with a bunch of guys. Over the years, from force of necessity, I created a male persona that was saturnine, cerebral, a bit remote, a bit owlish, possibly “quirky”, coming very close to asexual despite my best intentions.

Another reason for my repression was my sense that if I changed my gender it would obliterate every other thing I wanted to do in my life. I wanted to be a significant writer, and I did not want to be stuffed into a category. If I were transgender that fact would be the only thing anyone knew about me. Over the years, transgender people became gradually more visible in the media, and the coverage became a little bit less snide. I lived in New York City, so I saw transgender people often. I was close for a while to the photographer Nan Goldin, who would have been certain to understand my story, but I never breathed a word.

I would hear rumours that this or that person “dressed up” and I would be forever ill at ease in their presence as a result – from envy, of course. My office in the late 80s and early 90s was a block from Tompkins Square Park in the East Village, but I never so much as peeked in at Wigstock, the annual Labour Day drag festival that took place there. It was also half a block from the Pyramid Club – the centre of New York’s drag scene at the time – but I never went there, either. In those days the club had a black menu board on the sidewalk outside that read “Drink and be Mary”. I trembled every time I passed it.

I was terrified of finding myself confronted by what I am confronting now. I wanted with every particle of my being to be a woman, and that thought was pasted to my windshield, and yet I looked through it, having trained myself to do so. Now that the floodgates have opened I am consumed by the thought in a new way. When I uploaded my first picture to FaceApp I felt liquid and melting in the core of my body. Now I feel a column of fire.

That should not, however, imply a steely resolve. The idea of transitioning is endlessly seductive and endlessly terrifying. I take at least one selfie every day and transform it, and it feels as though the pictures are becoming ever-more plausible. With a bit of makeup, a course of oestrogen, and a really nice wig I could look exactly like that, maybe. But will the fact that I can’t grow my own hair make me feel like a fake for ever? And I am soon to turn 67. What if I look like a grotesque? Or merely pathetic?

It’s a vast decision, with the power to affect every aspect of my life. Would I inadvertently destroy important things in my life as a consequence? I keep wanting to be forced to transition by some circumstance, maybe my therapist telling me that it is crucial for my sanity. Anyway, I’m starting here, by writing it down – something I’ve never done before – and by sending it to a very few people whom I trust and who I think will understand. My name is Lucy Marie Sante, only one letter added to my deadname.

26 February 2021

That was written from within a whirlwind. I am astonished anew every time I consider the chronology. The first FaceApp manifestation occurred on 16 February. Ten days later I came out to my therapist, Dr G, who didn’t blink, but merely said she thought transitioning made sense and was a good idea. The following evening, after I’d written the letter, I came out to my partner, Mimi, which was the single most difficult thing of them all, and the day after that I came out to my son, Raphael. The fortification of secrets I’d spent nearly 60 years building and reinforcing had crumbled to dust in a little over a week.

The reaction was immediate: emails, phone calls, texts. Everyone was nice, although there was a range. There was “unexpected but not surprising” and “surprised but not surprised” and “shocking but not” at one end, and at the other were a few people who reacted as if they’d been hit by a train while they were looking the other way. Those tended mainly to be guys who over the course of many years’ friendship had come to think of me as a sort of mirror or alter ego, so re‐evaluating me meant having to re-evaluate themselves. Everybody on the “not surprised” end was female, as were the three persons who wrote to say they had happy tears in their eyes as they read my letter.

I was prepared for some kind of pushback, softly and judiciously expressed, of course, but it never really came, then or later. Most responses were yay, go for it, you do you.

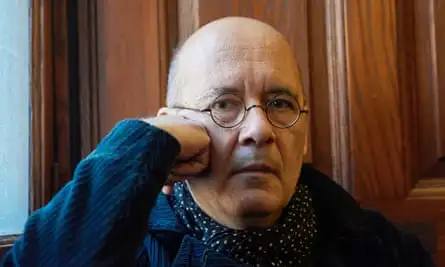

So now here I am, just shy of 18 months of hormone replacement therapy at this writing. I am legally Lucy, certified female, out to every single person in my life, however remote. I’m totally normal, the same person as ever, while also quite different. I’m socially at ease as never before. I’ve been stared at plenty, but have faced zero aggression, because I don’t represent a threat: I’m old, white, and reasonably privileged.

I can honestly say that I’m happy, in a way I’ve never been before. I am finally inhabiting myself, the shadow me once hidden under the floorboards. I actually feel free of the neuroses that plagued me for ever. I can and will of course be sad, for many reasons, but depression is at least at bay for now. I naturally wish I could have transitioned in my teens, or my 20s, or any age earlier than mine, but there are compensations: being left in peace, being able to nestle my changes into a life that was already structured, having outlived all the censorious elders. I genuinely like who I am – I’m turning out better than I’d imagined, or feared.

I’m more conscious of others and I find it far easier to bring up emotional matters with them. Often, in varied circumstances, I experience a kind of serenity, a general rightness with the world. I don’t hate myself any more, am no longer apologetic for my very existence. I walk with pride. I feel grateful to whatever force cracked my egg before it was too late. I was saved from drowning.