There’s a certain binary framework that I’ve never been a fan of, one that’s swept queer corners of social media over the past few years. Like all binary frameworks — cis or trans, queer or straight — it would sort us all into one of two camps: those of us who are transmisogyny-affected, or TMA, and those who are transmisogyny-exempt, or TME; in other words, you’ve got trans women, trans femmes, and others caught in the transmisogynistic crossfire on one side and everyone else on the other. As someone who’d fall into that former camp, I resent the idea of defining myself first and foremost through structural violence. More than that, it annoys me that we’ve essentially invented a clunkier way of saying something that we already have the words for. This framework aims to elucidate transmisogyny, a term coined by Julia Serano in her seminal 2007 feminist text Whipping Girl, as well as shed light on the ways in which certain trans people’s material realities diverge from everyone else’s, but all it does is create a circular logic that fails to explain much of anything.

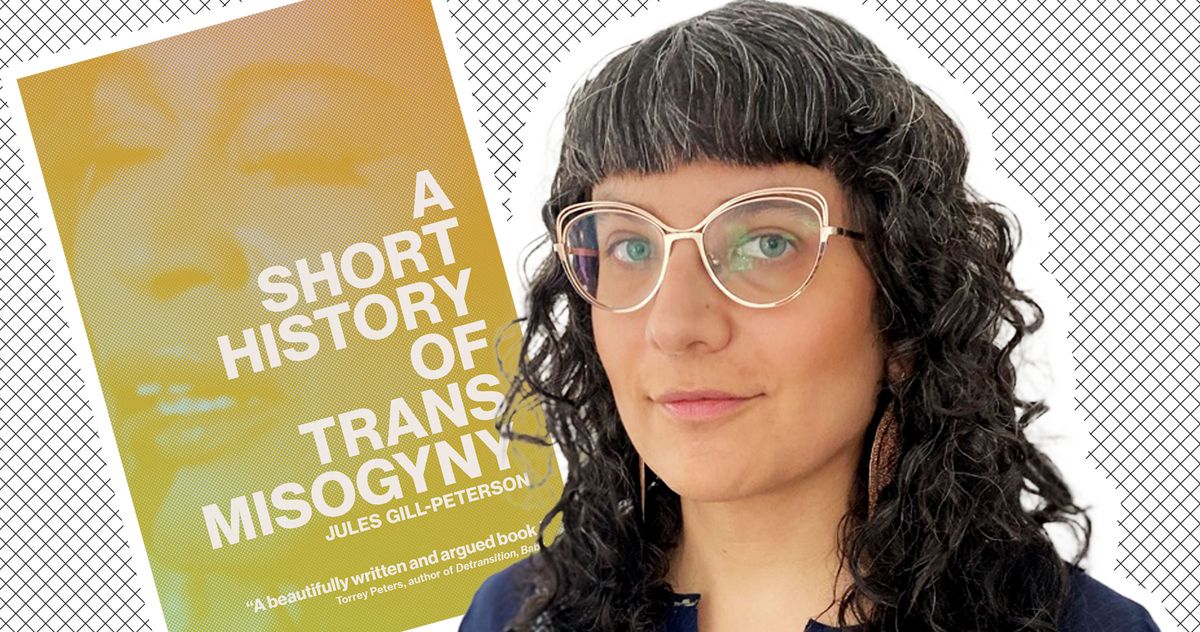

Thankfully, Jules Gill-Peterson offers an interesting and necessary intervention in her new book, A Short History of Trans Misogyny. (Gill-Peterson prefers to write “trans misogyny” out as two words, whereas I’ve always preferred “transmisogyny,” one word. Out of respect, I’ve alternated between them based on who is speaking.) In explicit opposition to the teleological explanation for transmisogyny — that trans women experience transmisogyny because we are trans women — Gill-Peterson charts a historical course back through the past few centuries of Euro-American colonial violence to locate the birth of transmisogyny as we know it. In doing so, she dispels the notion that one’s identity is the single determinative factor in one’s material reality. “I offer this book as a materialist case for leaving such losing games behind,” writes Gill-Peterson, an associate professor of history at Johns Hopkins University and author of 2018’s Lambda Literary Award–winning Histories of the Transgender Child. “There is no one who is purely affected by [trans misogyny] to the point of living in a state of total victimization, just as there is no one who lives entirely exempt from its machinations,” including cis people.

Note: In the interview, we discuss Cecilia Gentili, who passed away on Feb. 6, three weeks after our phone call. I’m choosing to leave the text as is, if only to preserve a moment in which she was still here with us. May she rest in power.

Your book is built on a radical premise: that trans women are not, in fact, destined for violence. How does that make you feel, that someone — e.g., me — might consider that premise to be radical?

Well, I think it’s true in the old-school sense of the word “radical,” as in, getting to the root of a problem. People from across the proverbial political spectrum, from those in the LGBTQ community to anti-trans politicians, all sort of agree in some way that trans women are destined for violence because it serves their interests in ways that converge. That convergence makes it something of a root problem for me, and that problem is trans misogyny.

You explicitly reject using the word “trans” as an all-purpose, catchall term to describe all transfeminine people. Why?

I’m just tired of the generic “trans.” The word “transgender” hasn’t been around for even quite as long as I have, but I don’t think it has a lot of great things to show for itself. The “trans umbrella” framework has a flattening effect that minimizes massive differences in living conditions between Black and brown trans women and all other trans people, whether we measure it by income, degree of criminalization, or rates of violence. And that awareness hasn’t resulted in an LGBTQ movement that actually fights for Black and brown trans women’s concrete interests.

Can you also unpack why you differentiate “trans women” from people who’ve been “trans-feminized,” that is, those whom the state has marked for violence through a process you call “trans-feminization”?

It began with me wanting to understand, historically, how trans women came to be treated differently and subjected to such exceptional hatred and violence, even among other trans people. But then I ran up against a brick wall because, well, not to reinvent one of the age-old problems of feminism, but if there’s no single, shared, common-denominator experience of womanhood — one of the critical assumptions of feminism for the past 30 years — then there’s not going to be one for trans womanhood either. There are many people who don’t necessarily share this Euro-American definition of “trans woman”: two-spirit people in the United States, hijras in British colonial India, travestis in Argentina. That’s where I came up with this phrase “trans-feminizing” to talk about the processes through which whole groups of people in the 19th century were targeted and subjected to this kind of violence that we call trans misogyny, but not because they were “trans women” in the way that we use that phrase in the United States today. To me, you have to understand the relationship between those two things in order to understand how vast the scope of trans misogyny has been — that it actually has a very long global history. Otherwise, you are sort of just continuing that fundamental violence of misrecognition that would misclassify people by forcing them into a concept that they themselves don’t necessarily identify with.

Yeah, your writing on travestis in Argentina reminded me of something Camila Sosa Villada wrote in the introduction to Las Malas [released in the U.S. as Bad Girls in 2022]. Have you read it?

No, I haven’t.

So, she opens with this note that her characters, who are all travesti sex workers, are not trans women or transsexuals or transgender or any other categorical identity “thrust upon us” by northern academics in the course of their anthropological research. For readers who might not understand, what is the problem with calling, say, travestis trans women or transgender? What is at stake?

Well, in writing this book, I was trying to look for antecedents to the trans misogynistic violence that we see today: “trans panic” defenses in court; violence in the sex-work industry; and disproportionate rates of intimate-partner violence, sexual assault, and murder. These things make headlines, in the United States in particular, but I wanted to see if we could trace similar kinds of violence backwards in time before that level of attention existed.

I found very similar patterns of violence instigated by men in positions of authority and male customers of the sex-work industry throughout the British and American military empires and their colonies around the world. That pattern recurred again and again, from the treatment of hijras all the way through to how American military-service personnel interact with transfeminine people in the Philippines, a former U.S. colony. Part of what stood out to me was that these were groups of people who were often pushed into sex work by larger geopolitical forces, despite having come from very different, culturally specific, sometimes religiously specific traditions in their respective home cultures. They were targeted by a western style of trans misogynistic violence, whether or not they identified as trans women.

This violence not only destroys those prior ways of life but, in fact, clears the way for their replacement with a medicalized, western model of trans womanhood. This new model invites people of the Global South to identify as transgender, understand their gender through the lens of gender dysphoria, and then transition in a particular, state-sanctioned, medicalized way — one that, more often than not, they can’t even access — or else they’re told they’re backwards and out of sync with modernity. It’s very much a western savior narrative, and the “rescuer remedy” to the specific form of violence these women are facing — basically, sending NGOs to help them learn that they’re trans women — is just perpetuating Euro-American dominance in those regions. That’s why, in my book, I lean into the fact that we don’t need a uniform concept of trans womanhood to understand trans misogyny.

That makes sense. We’re only a month into 2024, and lawmakers have already introduced more than 400 anti-trans bills nationwide — one of which, Ohio’s health-care ban, has already been passed into law.

These laws we’re seeing today, they’re not that shocking or exceptional as they follow a traceable line back through history. This anti-trans backlash is actually just the latest iteration of the very same repressive, trans-misogynistic state violence that has been the norm for the past 200 years, and it was only made possible because the state has encouraged people to see transfemininity as attackable for the past 200 years.

Argentina, for example, often gets held up as this gold standard of progressive, trans-inclusive legislation. In 2012, they adopted a gender-identity law that a lot of mainstream groups have been asking for. It relaxed the medical requirements needed to change your gender marker. You no longer had to undergo particular surgical procedures or be evaluated by a psychiatrist to change your documents; you could simply self-identify. One of the groups that came out in opposition to it, though, were travestis. In Argentina, theirs is a history of working-class transfeminine people who don’t identify exclusively as male or female. They tend to be sex workers, kind of adjacent to gay culture, and have a different relationship to physically transitioning that doesn’t fit a single mold. They’re a group of people who essentially don’t see themselves in the western medical model of “the transsexual,” who changes her sex through hormones and surgery and then changes her legal gender through bureaucratic means. This law prescribed only two categories through which you could identify to the state, man or woman, and since travestis are neither, it basically disestablished them under the law. This both creates a model of the good, productive, transgender citizen, which allows the state to extend its surveillance and control over people’s lives, and further devalues a whole group of people who do not fit into that model.

Populations who don’t fit into that moral order have been targeted continuously since the 19th century to be bludgeoned into conformity, whether that’s been done through criminal law or increasingly through this liberal soft power that aims to reform people into becoming normal, respectable woman-citizens. The public presence of hijras became such an extreme offense under British colonial sovereignty that police would stop them in the street, beat them forcibly, cut their hair, rip off their jewelry, and forcibly strip them out of their “women’s” clothing. At the same time in the United States, federal Indian Agents would use the same tactics on people who might today fall under the two-spirit umbrella: seeking them out, cutting their hair forcibly, ripping off their jewelry, and forcing them into male clothing. From there — the violent suppression of transfemininity on sight — we see the antecedents of modern anti-cross-dressing laws passed throughout the United States and other countries in Europe, which led to the kind of police harassment in the 20th century that people are familiar with.

It makes me think of the way that “defending queer rights” is used an argument for supporting Israel. Can you think of any historical examples that might help us understand what’s happening here? It feels like a Bush-era redux — like, those claims that invading Iraq and Afghanistan would somehow advance women’s rights.

I mean, it’s not just a redux of the Bush era because the so-called “war on terror” never ended.

True.

It’s been perpetuated by every subsequent U.S. administration. Something that helps me make sense of this horrifying absurdism is Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s famous phrase, “white men saving brown women from brown men.” This specific example of pinkwashing is built on a perverse fantasy that goes back to something from the start of our conversation: universalizing a culturally specific, white, middle-class, transgender subject and applying it to every culture around the world as a hallmark of modernity, which you can then use as a cudgel when you don’t see it reflected back exactly. You’re just universalizing one culture as the only standard through which every other culture in the world gets to be judged.

Part of what’s been so devastating to me is that there’s actually no “gotcha” in pointing out that hypocrisy. An American can use the idea of trans women in Gaza to justify genocide against her people while trans women in the United States are experiencing such horrific political backlash.

What role, if any, do you think transmisogyny will play in the 2024 election?

Oh, trans misogyny is surely going to play a significant role in the 2024 election. Candidates running for president have tried to out-anti-trans one another by proposing increasingly harsh policies — you know, like national bans on transition-related health care, which are obviously very closely tied to the efforts to ban abortion nationwide. It has escalated to the point that right-wing political figures and their media surrogates feel comfortable making public claims about eradicating “transgenderism.” People understand that transphobia is central to the Republican Party, but to my mind, a lot of their anti-trans politics are specifically trans misogynist. They have incited an alarmist moral panic that always comes back to trans women: that they aren’t women, that they are men dressed as women, that they are a symptom of moral disorder, that their rise in number is so disgraceful that we should get rid of them to secure the nation’s safety. It’s a rhetoric that intersects with the kind of dehumanizing language generally reserved for migrants, the kind of language that serves as a predicate for projects of mass incarceration and extermination.

On the flip side, though, we have the mainstream defense of trans people that banks on the authority of doctors, psychiatrists, and various studies to support trans people’s validity. “The science says it’s okay for me to wear the clothes that I wear every day” and other absolutely bizarre contortions have become so normalized. Sometimes, when I actually stop and listen to what the national LGBTQ organizations are saying in my defense, on my behalf, I just think: We have lost the plot, right? The Democratic agenda is focused on maintaining the status quo, which presents the 2024 election as a kind of doomsday showdown. On the one hand, you have this guy promising to inflict the worst thing that’ll ever happen to you in your entire life but hasn’t happened yet, and then you have this other guy promising the second-worst thing that’ll ever happen to you in your entire life but has already happened, which is the status quo: limited access to substandard health care, criminalization, the targeting of sex workers, internet surveillance, poverty, mass incarceration, and the continued structural violence that trans women are already facing. One might be worse than the other, but it is nothing if not delusional to pretend that one side is pro-trans and the other is not.

The only movement I’m interested in being a part of is one where trans women’s needs and interests are the ones that we’re fighting for, and you know why? Trans women make do in the worst possible situations, and getting the things that they want would make things better for everyone else.

Who do you think is doing important, interesting work in the field of trans studies right now? Whose work excites you?

Well, I’m happy to say, as someone who works in that field, that academic trans studies is not the thing that’s producing the interesting work that inspires me. That doesn’t shock me, though; the academy is generally responsible for the worst ideas about trans people, historically speaking, so it’s hard for academic trans studies to break with that. I find a lot of inspiration elsewhere — certainly cultural producers who are trans women are people who inspire me. I can’t help but think of Cecilia Gentili in particular, her book Faltas. I’ve seen clips from some of her shows, but I haven’t had the chance to attend in person. Her storytelling draws on a raw power that comes from a lifetime of experience. Like she’s lived several lifetimes, quantitatively, in her time on earth and is therefore a lot wiser than most of us and finds a way to tell us that gently and thoughtfully, and with a lot of laughter, while telling it on her own terms and getting the last word.

Oh, she’s fantastic. Her Off Broadway show, Red Ink, is coming back for another encore performance, actually.

There’s so much cultural production happening with trans women. They have the least resources and have to work so many times harder than everyone else — I’m just so impressed when someone trans gets something published, gets a film out there, lands a new gig. We’re living in one of the first periods in a long time when trans women, as a class, can dare to work in a wide range of fields, including creative fields, and be recognized for their talent. Every single one of those women out there hustling and producing innovative work that everyone else is then going to copy and steal from in inferior forms, those are the ones who impress me. That’s something that gets me up in the morning and keeps me excited to continue my own work, because thanks to the circumstances under which they are forced to live, trans women in general tend to be the most brilliant, thoughtful, analytic, funniest, creative people I’ve ever met. I just can’t wait to see what each and every one of them has to share with us.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Inventing a Trans Panic

Leave a Comment