Before setting off to the clinic for his monthly refill of antiretroviral drugs (ARVs), Himena* has a ritual. He removes his ear pins and wears a hoodie to cover his braided hair.

Since the passing of Uganda’s Anti-Homosexuality Act (AHA) last April, Himena, a gay man, has felt increasingly unsafe. Even at a donor-aided clinic that provides HIV/AIDS services and is located at a government hospital.

“I can’t just act freely. I’m scared that I’m easy to spot from the queue,” he told openDemocracy. Last month, as Himena waited in a queue, another queer patient – visibly sporting lip balm and painted nails – was pulled out of the line by a health worker who asked, “What’s wrong with you?” and made them wait away from the reception area. Himena said such homophobic and stigmatising actions by health workers have increased at the clinic since AHA was passed.

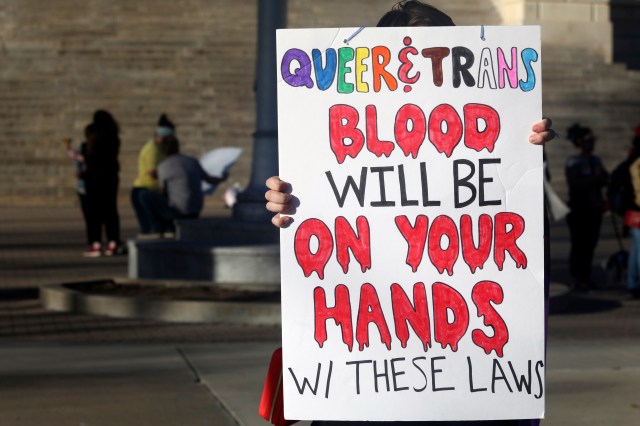

Earlier this month, after hearing a petition from 22 individuals and organisations challenging the AHA, Uganda’s constitutional court refused to annul it in its entirety – and rejected arguments that the law infringes on the constitutional rights and freedoms of LGBTIQ Ugandans.

But the court did strike down four of the AHA’s clauses, including one it said violated LGBTIQ+ people’s access to health, especially HIV/AIDS treatment and care.

At face value, this might seem a win of sorts for queer Ugandans, and has been celebrated as such by some campaigners who believe that their right and access to healthcare has been protected.

But the annulments have also been criticised by many as an attempt to sanitise an otherwise horrific ruling. Nicholas Opiyo, a lawyer to the petitioners, told reporters at the court it was a “failed attempt at a balancing act”.

“If you can’t express yourself or rent a house in this country, what is there to say you have a right to health?” he asked.

A right to health or a trap?

For many queer Ugandans, the arrests, evictions and attacks they have suffered since AHA was passed disprove any suggestion that their right to healthcare has now been protected.

“I’ve not felt any reassurance. The [AHA] has already done its damage,” said Himena.

While the court guarantees access to health services, fears remain that messaging around healthcare may fall under the “promotion” of homosexuality, a vague and overreaching offence punishable by up to 20 years in prison.

Health educators also worry that people could also be arrested for the possession of medical products like lubricants and pre-exposure prophylaxis (or PrEP) – medicine taken to prevent contracting HIV – and that the number of people accessing health services is likely to remain low. The rate of gay patients attending a major referral hospital in eastern Uganda for treatment has fallen from about 300 last year to a little over 100, according to Emma*, a doctor offering HIV/AIDS services, who asked that only their first name be used out of fear of reprisal.

“The government is basically saying, ‘If we catch you doing this, we’ll imprison you, but if you do it, you can still access medication’. The queer community I supply medicine to see it as a trap,” Jovan Nyanzi, a transwoman sex worker and peer health educator in eastern Uganda told openDemocracy.

Nyanzi is part of a network of peer health educators around the country who have played a central role in queer health access by collecting HIV/AIDS medication, contraception and lubricants from health centres and delivering them to LGBTIQ+ people who are unable to visit in person.

For Nyanzi, before the AHA, between 50 and 60 queer HIV/AIDS patients would pick up medication from her each month. Since the AHA was introduced, that number has more than halved.

Medication itself is also known to be used by the police to incriminate LGBTIQ people under the AHA. Last December, the Ugandan police in Busia, a border town with Kenya, arrested Kasana*, a gay man, and his friend after finding self-testing kits and lubricants in their bag. They were held for four days and subjected to forced anal examinations and blood tests, and later charged with the “offence” of “homosexuality”, for which the AHA prescribes a life sentence.

“They insisted on knowing what we were using the lubricant for. But we soon realised they already knew,” Kasana told openDemocracy last week.

Kasana’s experience is not an isolated one.

Many of Nyanzi’s patients have resorted to repackaging PrEP and lubricants into recycled tins for fear of being caught with them by the authorities.

There is also a concern that previous efforts by queer organisations to train the police on LGBTIQ rights – including by educating them on medical products that people may use – are now being weaponized against the community.

The court’s upholding of the right to healthcare appears inconsistent with other parts of its ruling. Although it recognised research and data showing that the community of men who have sex with men (MSM) in Uganda is particularly vulnerable to, and at risk of, contracting HIV/AIDS, the court also found that “physical harm” from anal sex “imposes a burden on the health system” and that HIV infection rates “place a worrisome disease burden on national health systems”.

Ugandan health campaigners say this is hypocritical, pointing out that the judgement ignores the relationship between and the rise in HIV rates in the queer community.

“Promotion” of homosexuality or health messaging?

Queer organisations that offer health services, such as IceBreakers Uganda (IBU), could still be at risk of breaking the AHA under its “promotion of homosexuality” clause – which criminalises someone who “encourages or persuades another” to have gay sex or commit any other offence under the act.

This also extends to the financing of gay work or activities, and knowingly advertising or publishing material or running an organisation that “promotes”, “encourages” or “normalises” homosexuality.

The thin line between positive health messaging for LGBTIQ people, and promotion of homosexuality will be “tricky” but the “strategy is to go less specific”, according to Bob Bwana, an activist at IBU.

“If I’m promoting condom use I’ll not say it’s for queer people, and I can’t use rainbows because it’s been demonised,” he said.

“The disadvantage is that it leaves out the group the message is supposed to be targeting. Some people will stay away,” he added.

Many peer educators have reportedly left their work too in fear of arrest under the so-called “promotion” of homosexuality, and medical workers at government health centres sometimes treat them with suspicion and contempt.

LGBTIQ health-focused clinics, however, are determined to continue their work. “We are going to continue giving our clients the services they deserve,” said Bwana. “[We shall not be] intimidated by claims of ‘promotion’ of homosexuality.”

Are the health concessions for Ugandans or to please foreign donors?

Campaigners have interpreted the annulled clauses in the AHA as a thinly veiled signal to international funders of Uganda’s health sector, especially its HIV/AIDS work.

Last August, the World Bank froze new lending to Uganda following the passing of the AHA, which the institution said “contradicts the World Bank Group’s values”. PEPFAR also planning for Uganda beyond 2023, for the same reason. The US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) gives Uganda about $500m a year, while the Global Fund spent $277m between 2021 and 2023 on HIV work.

Some of the annulled clauses had targeted LGBTIQ people living with HIV or placed a burden on citizens – including health professionals – to report suspected homosexuals. Now the court believes these clauses are a violation of access to health services.

Adrian Jjuuko, one of the petitioners in the case, on X (formerly Twitter): “The govt always thought this is what donors need to see off the law books for the money to flow.”

“Upholding the right to health would mean nullifying the law (entirely),” said Asia Russell, the executive director of Global Access Project (Health GAP), an international organisation focused on universal access to HIV/AIDS care.

“The judges removed merely 1% of the harm. By retaining 99% of this deplorable law, Ugandans’ right to health is deeply undermined.”

Russell also spoke out against the complicity of Western donor governments through their continued dealings with the Ugandan government.

In response to the court ruling, PEPFAR that it was “deeply troubled by reports of human rights abuses in Uganda” and that the ruling was ‘major blow… especially those of LGBTQI+ persons and their allies,” but it would continue its programming in Uganda.

PEPFAR and the World Bank did not respond to openDemocracy’s requests for comment.

The ruling should prompt further restrictions on donor funding, according to Frank Mugisha, head of Sexual Minorities Uganda (SMUG) in a statement Convening For Equality, a coalition of LGBTIQ leaders and allies, based in Uganda

“No donor should be funding anti-LGBTIQ hate and human rights violations.”

*Names of some sources in this piece have been anonymised for their safety.