This could force transgender candidates to circulate petitions using their deadname — the name they used before their transition. Also, the rule is not listed in the state’s official candidate requirement guide and the petitions themselves do not appear to have spaces for candidates to list former names.

The Montgomery County Board of Elections on Tuesday affirmed the candidacy of Bobbie Arnold, a transgender woman from West Alexandria who petitioned with only her current name.

Arnold filed to run in the Democratic primary for an Ohio House seat representing Preble County, western portions of Montgomery County and northern Butler County.

Board of Elections Director Jeff Rezabek, a Republican, told the board that Arnold met every requirement in the state’s candidate handbook.

“This board is always asked whether the individuals signing the petition were misled as to who they were signing for, and what position that candidate was running for,” Rezabek told the board, recommending no action be taken against Arnold’s petitions. “And in this case, we believe that those individuals were not.”

“I had no idea about this law,” Arnold told this news outlet Tuesday. “And, had I known, I would have put my former name down.”

Arnold legally changed her name in 2021.

Arnold’s petitions were not formally protested by any elector within the 40th House District before the Jan. 5 deadline to do so. However, Montgomery County prosecutors had requested the board hold a formal review of the petitions, which resulted in Tuesday’s meeting.

Other Ohio candidates

The law led to the disqualification of a previously-certified transgender candidate in Stark County early this year and is at the center of debates surrounding candidates like Arnold and another transgender candidate in Auglaize County who has her own disqualification hearing Thursday.

Another transgender candidate in Athens County has not had any issues with the law because he has not legally changed his name and petitioned with his former name.

The Ohio law has existed in some form since as early as the 1920s, and the current version has been in place since the 1990s. It’s rarely been enforced in Ohio over the decades, usually in response to candidates wishing to use a nickname on the ballot.

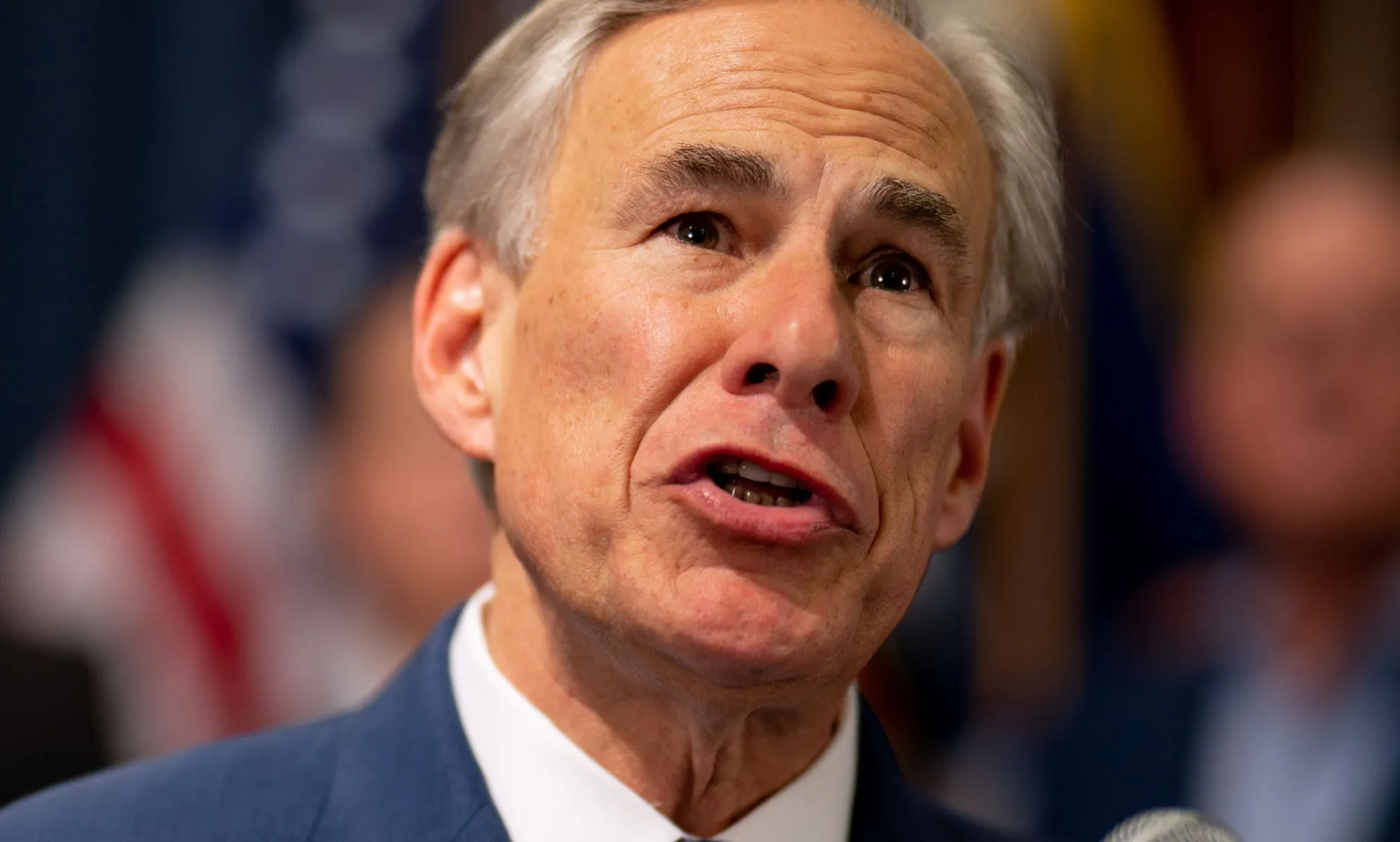

Republican Secretary of State Frank LaRose told the Associated Press that he and his team are looking into noting the law in the candidate guide, but that his office is not open to changing it.

He said that it’s important for people to disclose who they are and any former identities, so the voters know who is asking to be put on the ballot.

“Candidates for public office don’t get anonymity,” LaRose said, also noting that the guide carries a disclaimer that it does not list every rule and that candidates should seek counsel on any additional rules that could impact them.

But to the transgender community, revealing what’s commonly called a deadname — or the name assigned to them at birth that doesn’t align with their gender identity — could lead to personal safety issues.

Zooey Zephyr, a transgender Montana lawmaker who was silenced by the Montana state House, had her name change records legally sealed prior to holding office. However, she said that didn’t stop people from trying to dig up her birth certificate and harass and threaten people connected to her deadname.

Zephyr said she also finds LaRose’s argument about candidates not getting anonymity “hollow” since the statute exempts name changes due to marriage.

“For the Secretary of State to say public figures don’t get anonymity while allowing that for women who are getting married fails to recognize the seriousness of the issue for trans people,” she said.