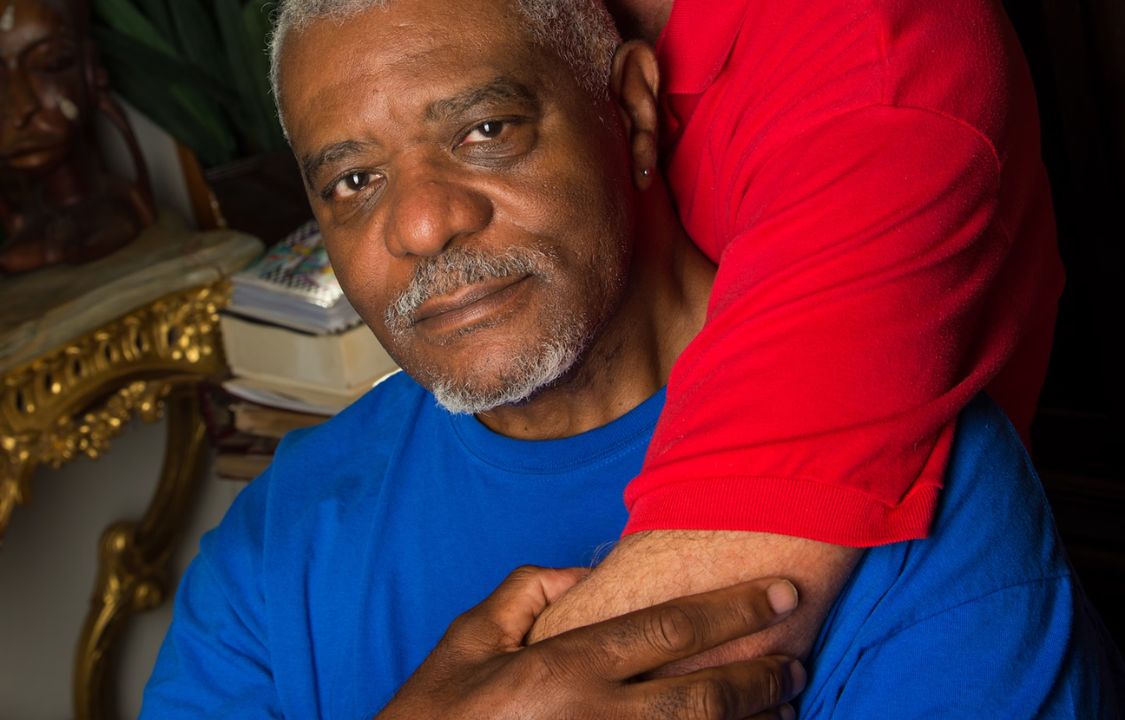

Billy S. Jones-Hennin attended his second gay pride event on the streets of Washington, but he remained glued to the sidelines, a witness hesitant to join the celebration despite his desire to do so. Mr. Jones-Hennin, a Black bisexual who was born in the West Indies and raised in conventional Virginia, was afraid of expressing his sexuality in public at the time. It was the middle of the 1970s.

But as he observed the partygoers pass by while holding arms and cuddling, everything changed. The rally revealed to me the sheer number of people who shared my traits, including people of all ages, ethnicities, and professions. In a 1987 discussion with The Washington Post, he recalled that they were “different.” The celebration and the Pride events that came after each June helped him reach a point where “I can be me every day for 24 hours.”

Mr. Jones-Hennin rose to prominence as one of the country’s leading defenders of LGBTQ+ freedom, particularly on behalf of LGBT+ people of color, within a few years of his first Pride event.

He co-founded the first national institution for Black lesbians and homosexuals, which started out as a social alliance in Washington and Baltimore. He oversaw the preparations for the first National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights, which attracted at least tens of thousands of attendees in 1979. Additionally, he assisted in setting up what is frequently referred to as the primary LGBTQ+ group of color to visit the White House that year. He and a few allies met with Carter administration aides to discuss housing, healthcare, and discrimination.

According to Victoria Kirby York, the public policy and programs director for the National Black Justice Coalition, an LGBTQ+ rights organization, Mr. Jones-Hennin “didn’t just lament what was happening” as conservatives organized against gay rights. Knowing that was the only way we would achieve liberation, he strategized, organized, and persuaded people who wouldn’t otherwise want to be in the same room together to do so.

After his health declined in the late 1990s and spinal stenosis started to restrict his mobility, Mr. Jones-Hennin focused on disability rights. He oversaw wellness programs in Washington, D.C., during the 1980s AIDS crisis. He passed away on January 19 at the age of 81 at his residence in Chetumal, Mexico, where he spent the winter. In Washington, he even owned a house.

According to his partner Cris Hennin, complications from Parkinson’s disease and spinal stenosis were the root of the problem.

In 1978, Mr. Jones-Hennin, a charismatic public speaker with an aptitude for forming coalitions that cut across racial, gender, and group lines, moved to the forefront of LGBTQ+ activism. The town was primarily Black at the time, but its LGBTQ+ group had a White face. Being the only Black man often attending meetings of organizations like the Gay Activists Alliance had grown old to Mr. Jones-Hennin.

He co-founded the D.C. and Baltimore Coalition of Black Gays with a few like-minded protesters, holding the group’s inaugural meeting close to Dupont Circle. The National Coalition of Black Lesbians and Gays, which had chapters in New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago, promoted what would later be known as an integrative strategy for campaigning. “As proud of our sexuality as we are of our blackness” was their tagline.

Due to that, there was no compatibility between a queer and black identity. Gil Gerald, a co-founder and the organization’s first paid executive director, said, “You couldn’t bring it together.” (Organizations like the National Black Justice Coalition took over the organization after it disintegrated in the late 1980s.) “White was Gay. Black? Well, that was Black, I guess.” He added, “We found our message through his organizing,” and referred to Mr. Jones-Hennin as “the origin, the spark.”

Mr. Jones-Hennin claimed that he was motivated by two objectives: overcoming prejudice in the lesbian community and bigotry among the Black community. He supported the coalition while also acting as the logistics consultant for the first national Gay march on Washington, a grassroots social movement that was organized following the assassination of openly gay San Francisco politician Harvey Milk in 1978. Speakers at the event, including authors Audre Lorde and Allen Ginsberg, urged Congress to enact comprehensive policy defending homosexual and gay rights.

“There were neither tools nor funds.” According to Susan Silber, a Washington-area attorney who volunteered to work the occasion with Mr. Jones-Hennin, it was “just completely soul.” She was a co-parent to two of his children (decades later).

Because it had never been done before, she continued, “We never knew if people would come.” “We weren’t sure if people would be open to being seen. Billy was the one who made sure the buses arrived, along with

one or two other people, and you couldn’t have predicted it until it actually happened.”

Mr. Jones-Hennin organized a “Third World” LGBT meeting the exact trip to make sure that African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and other people of color were represented at the protest. It was billed as the first national meeting of LGBT people of color and was held at the Harambee House hotel close to Howard University.

Sessions included topics like “Consciousness Raising,” “Chicano Identity,” and “Black Gays of the South,” as well as “Alcoholism,” The Dynamics of the Prison System, and The Mature Lesbian. It was disco day on Saturday evening. Lorde delivered the keynote discourse, though Mr. Jones-Hennin later acknowledged that he was so exhausted from the planning that he missed it.

“Did I remember to zip up my fly when you’re on the front lines organizing—and even the day before that—you run around taking care of the little details, dealing with the hotel, and handling the spectators while trying to laugh? Do I also have the appropriate attire? Thank you!” In a 2007 meeting with Metro Weekly, he stated. “Do you really think I’ll just watch a speech from that?” I dozed off. However, I was present.

On March 21, 1942, Lannie Bess, as he was formerly known, was born in Antigua and Barbuda’s capital city of St. John. He was raised in Richmond by a family who gave him the title Allen Billy Scott Jones when he was 3 years old. Mr. Jones-Hennin finally made the decision to shorten his title by adding an ‘An’ to Billy after going by the name A. Billy S.

According to Mr. Jones-Hennin’s home, his dad was a doctor, and his parents raised 10 adopted children in total while converting their home into an inpatient and nursing facility.

Mr. Jones-Hennin claimed that he joined his relatives in Richmond to protest against segregated department stores and afterward went to the 1963 March on Washington for civil rights.

Years later, he told the New York Times, “The communications that day were as important to me as they were to a Black man.”

In an age when, according to him, bisexual men were shunned or ignored within the gay community, he had begun to identify as a gay man by the time of the march and was on his way to using the term “bisexual.”

His family revealed that he was gay after his father passed away, despite the fact that his parents were usually supportive. When Mr. Jones-Hennin came out to his father, he was told “that I needed to be aware of sexually transmitted diseases, I should get married and have kids, and that I should be discreet,” according to an oral history for the LGBT library Outwords. I did it. I did marry a woman whom I also adore today. (After seven years, he and his wife split up.)

Mr. Jones-Hennin studied business and accounting at Virginia State College (now a university) after serving in the Marine Corps, graduating in 1968. He earned a master’s degree in social work from Howard in 1990, according to his LinkedIn profile.

He had moved to the District by the early 1970s and was residing in Columbia, Maryland, before settling in the Washington area. He joined the Gay Married Men’s Association, or GAMMA, in its Washington branch as a founding member in 1978. The organization was established as a support group in response to the Cinema Follies fire, which resulted in the deaths of nine people trapped inside.

Hennin, his future partner, was introduced to him through the group. They got engaged quickly, and in 2014 they got married. Three of his children from his first marriage—Valie Jones of Las Vegas, Anthony “TJ” Jones from Manhattan, and Forrest “Frost” Taylor of Atlanta—as well as two offspring from their relationship and relationship to Hennin, Danielle Silber of Croton-on-Hudson, New York, a sister, 10 great-grandchildren, are among the survivors, along with his partner from Washington and Chetumal.

Mr. Jones-Hennin lived briefly on the West Coast in the 1980s, despite spending the majority of his career in Washington. He was found to have stolen between $14,000 and $57,000 from a San Francisco social services organization where he worked as an accountant in 1985, leading to his sentence of one year in prison for larceny.

Billy’s husband wrote in an email, “The abuse of cocaine was motivated by his work ethic and dedication to social change, which resulted in the larceny from his employer.” Billy “became a strong advocate for individuals struggling with addiction recovery as he was confronted by the problems and conflicts of his habit.”

After being freed, he went back to Washington and started working at the Whitman-Walker wellness center, managing HIV/AIDS support and protection plans for vulnerable populations like sex workers and people who use intravenous drugs. Eventually, he oversaw the National AIDS Network’s minority affairs division.

While continuing his advocacy work, Mr. Jones-Hennin worked as a researcher and technical chairman at Macro International, a consulting firm based in Washington that worked with government agencies. He co-chaired the interracial National Association of Black and White Men Together, helped found the political party Langston Hughes-Eleanor Roosevelt Democratic Club, and served on an advisory committee that collaborated with the D.C. administration on accessibility issues.

In an interview with Metro Weekly, he stated, “I am an activist until death do us part.” You may take a step back once it enters your blood, but you can’t take it away.