Who our reading is for is one of the questions that trans authors today wrestle with: many writers from the community want to read books that appeal to other trans people, but publishers frequently pressure those authors to write stories that may appeal to the much larger cis population.

Torrey Peters pioneered the field of trans writers by daring to write books that put her personality as an artist and a trans person at the top of the list. Freddy McConnell, a trans journalist, once said that she stops viewing herself as political and rather assumes total creative freedom. This is not a common practice among cis writers, who are still routinely expected to deliver didactic stories for a cis market. But in an appointment in The Guardian with McConnell, Peters made it clear that her 2021 book Detransition, Baby was written without any such expectations: “I had the liberty to think of trans people as simply mundane, boring, imperfect people. I wasn’t engaging with trans people as an embattled group”.

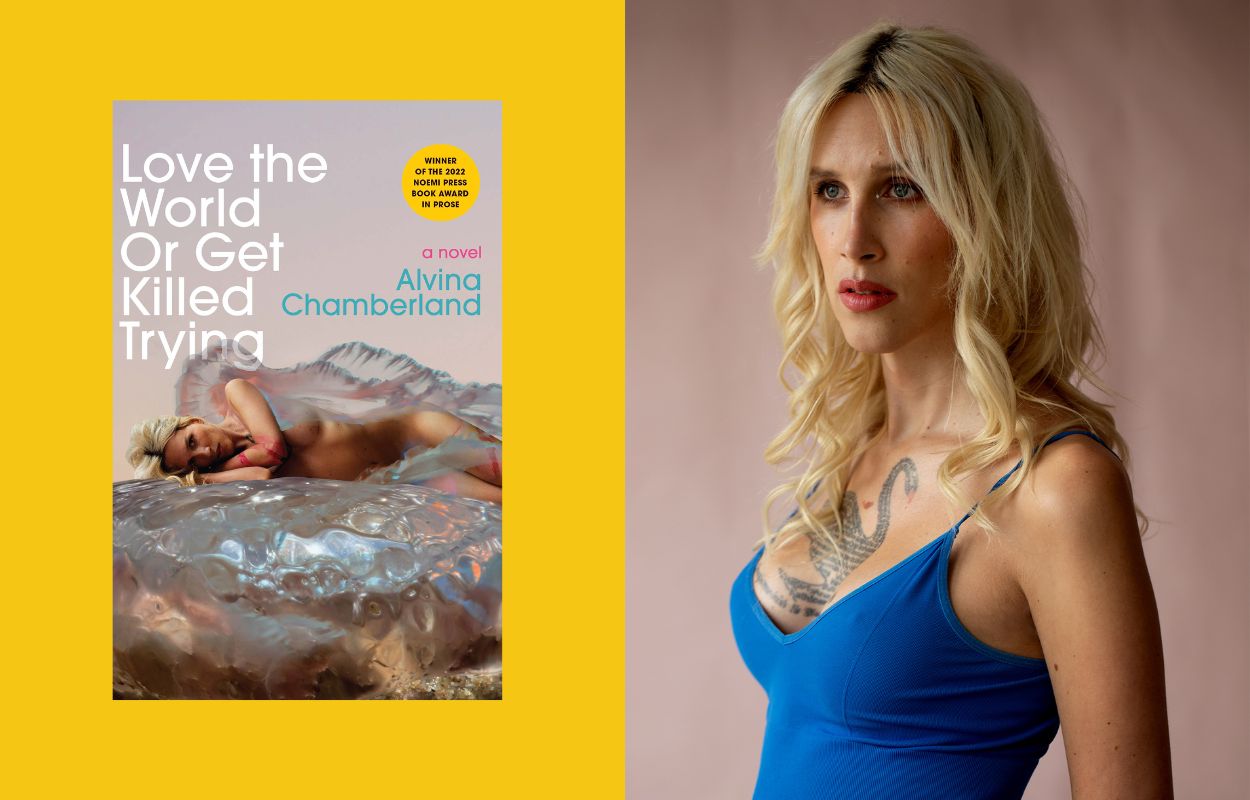

Peters is one of a small but growing number of transgender storytellers who dare to tell our life to the level of our society. We can now add another name to this list with the debut English-language novel from Alvina Chamberland (following two Swedish autofiction works), Love the World or Get Killed Trying. This guide immerses itself in the injury that “stubbornly refuses to fit into distinct incidents with basic stories that make it easy for anyone to sympathize,” to estimate the author herself. It is one of those books that more than the personality and fascination of its words propels itself ahead. And Chamberland’s words are often quite powerful.

Love the World or Get Shot Trying immediately makes its odd sensibilities known, which depict the narrator’s apparent rape in a manic, drily humorous stream of consciousness right from the start of the book. Consider it a quick acid test of whether you, as a reader, will want to proceed. Those who find this opening powerful will remain to witness the turbulent torrent of awareness of the narrator Alvina as she navigates a trip to Iceland, where she intends to lick her wounds and see if she can beat her deep sense of isolation and alienation as a trans woman.

The roughly the first half of the book’s first half is a beautifully wrought evocation of a fundamental characteristic of the trans experience: that unending sense of unsteadiness when it is never quite clear if you are fitting in or not. Alvina repeatedly gets her hopes up until the men realize she is trans and send her a string of heartbreaking rejections during some evenings at clubs in Reykjavik. I quickly become uneasy, afraid of being treated with patronizing sympathy and scapegoated as the freak of the evening. I have a bad feeling about the Scandinavian brand of reserve that causes my mind to think that everyone dislikes me, that I am dirty, and that I should be swept aside despite not being in the way. It is a common enough experience, to seek acceptance by the cis world, and even to receive it to an extent, only to eventually realize that you have been othered by your transness.

As part of Meta’s response to Bill C18, Xtra is being blocked on Facebook and Instagram for Canadians. Stay connected, and tell a friend.

She can write morbid comedy all day and write set pieces. Love the World or Get Killed Trying features Icelandic characters that Alvina visits glaciers, stunning waterfalls, and idyllic beaches. Her thoughts never stop returning to her plight as a trans woman, even in the splendors of a landscape that resembles Game of Thrones. “The last century was a psychopath. This one is still a teenager. In the city I’m forced to be an object, and my rebellion: a flood of tears. I am: a crying object, crying, screaming to survive her own life. influenced by their conviction that we do not share the characteristics of breathing in and out carbon dioxide.

What happens in Love the World or Get Killed Trying’s second half, when Alvina returns to her home in Berlin, will likely divide readers: essentially, Chamberland doubles down on the plaintive wail of bitter otherness and isolation. Alvina continues to go through the same tortures as a book that might have given her some reason to hope or at least counteracted her cry of pain with some form of catharsis. It is a rough thing for a reader to experience, and Chamberland knows it. The more harrowing shit you’ve lived through the less people will want to hold you, she aphoristically yells at us.

In my read of Detransition, Baby, what made that book such a remarkable success was how Peters gave her trans lead, Reese, two foils: Reese’s close friend, Ames, who has recently detransitioned back to male, and Ames’s lover, Katrina, a cis woman who may ultimately form a family with Reese and Ames. Although we share her feelings, Reese is a very flawed individual, and Ames and Katrina, who support Reese’s development as a person, soften the sharper edges of her unbalanced personality. Reese’s character escapes the threat of solipsism because she is made to look outside and take into account the experiences of others. For me, this made Detransition, Baby remarkably complex and truthful, saving it from falling into complaint-porn.

In Love the World or Get Killed Trying, we don’t hear any of these voices. Alvina’s complaints about the cis world keep piling up, and her mistreatment stories keep coming in unabated, making the book darker, pessimistic, and more closed. Chamberland herself recognizes what she’s doing when she writes, “I know, reader, I seem to be obsessed with repeating these anecdotes to you. It’s not my intention. If it gives you a headache to read, what do you think it’s like to live”? Unlike with Detransition, Baby, there is no point where Alvina experiences anything resembling transcendence. The book just gets worse, and it gets more and more isolated in and of itself.

As an elaborate portrait of a trans woman’s suffering, Love the World or Get Killed Trying is exquisite. Chamberland’s prose is sharp, surprising, often funny, aphoristic and relentlessly inventive. It completely sets it apart from other trans-experienced books I’ve read.

I’m hesitant because I don’t know whether it was the right decision to focus so heavily on Alvina’s suffering. In lines like this, Chamberland expresses the sensibility of her literary heroine Clarice Lispector, who she names in the book’s afterword, and how she learned to sit with it, endure it alone, feel the quivering vibrations, and then experience a transformation: the kind of euphoria that glows in lives that have been euphorized and been fertilized with the alertness of a birth-scream. Such writing is purposefully overwrought and overdramatic in the tradition of the great Brazilian, which helps it convey a powerful sense of truth that less heated writing could not. At the length of a nearly 300-page novel, however, the relentlessness of Chamberland’s vision does come to feel bleakly excessive.

The issues raised by Love the World or Get Killed Trying raise complex issues of trans representation in literature. On the one hand, it’s wonderful that a book like this can exist; it’s a stream-of-consciousness prose poem of raw, unadulterated trans experience, much of it shockingly abysmal. But on the other hand, one wonders if our