Transgender rights advocates worry that the NCAA might follow suit after the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics votes on Monday to bar transgender women from women’s events starting the following school term.

At the NAIA’s federal agreement, the Council of Presidents determined that beginning Aug. 1, “only individuals whose biological sex is female” may participate in women’s activities. That includes trans people or nonbinary students who do not undergo masculinizing hormone therapy.

In a press release, NAIA President and CEO Jim Carr stated that “we are unwavering in our support of fair competition for our student athletes.” “It is crucial that NAIA member institutions, meetings, and student-athletes participate in an atmosphere that is equitable and respectful. The NAIA’s Council of Presidents has established our course of action following input from our member institutions and the Transgender Task Force.

With 241 member institutions, most of them private with relatively low admissions, the NAIA is overshadowed in size and influence by the NCAA, whose teams and events, including yesterday’s men’s hockey title game, are among the most popular in American sports.

Trans athletes may compete under the supervision of their international sports governing bodies, per NCAA rules. The NCAA has previously advocated for inclusion but has been in opposition to states’ requests to prevent trans athletes from competing in public school activities.

The NAIA vote, according to Anna Baeth, director of research for the LGBTQ+ sports lobbying group Athlete Ally, suggests that the NCAA might have similar latitude. That sense of latitude, in my opinion, would be very misguided.

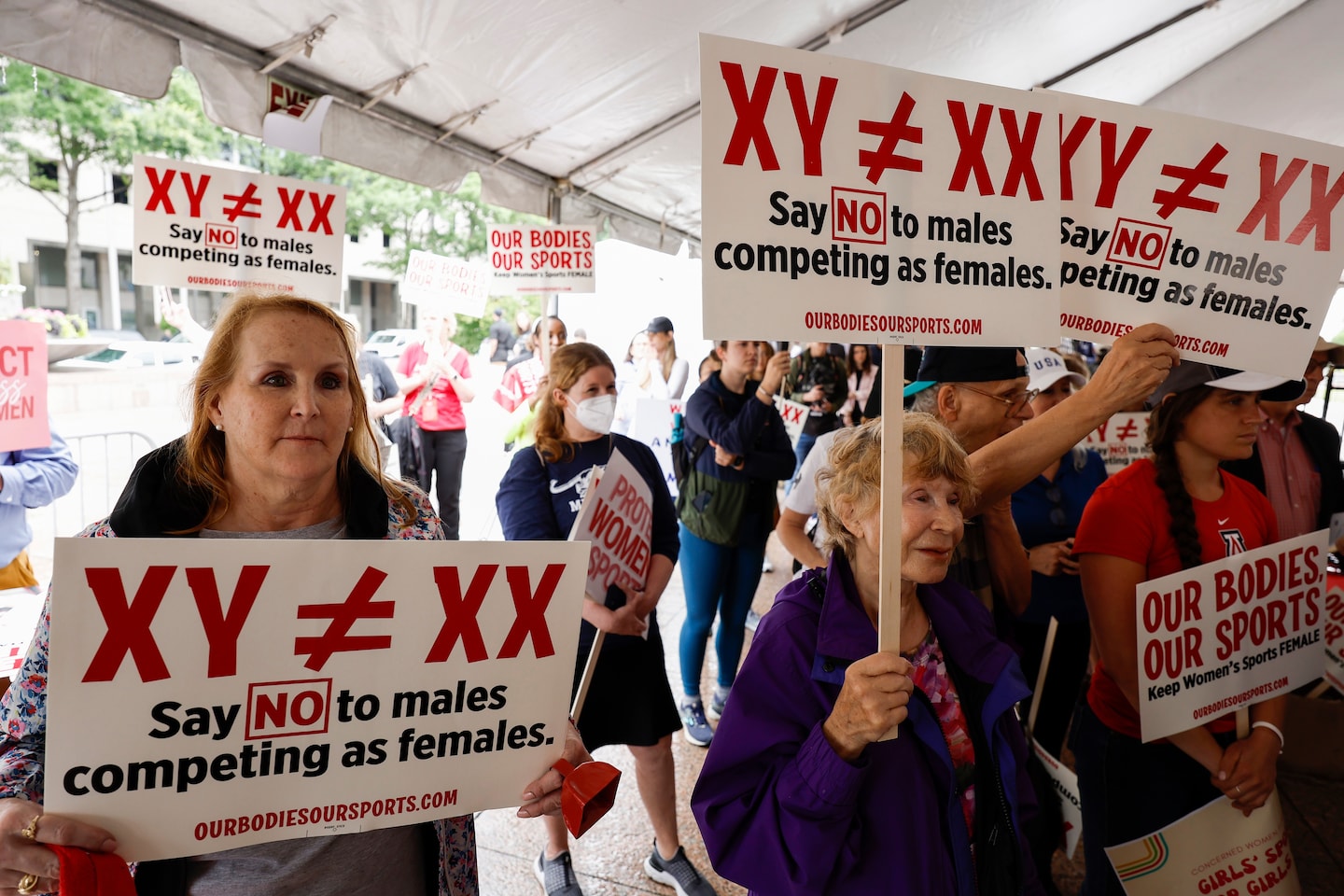

Criticism and scrutiny of trans-athletic rights have long been contentious, particularly at the K-12, college, and Olympic levels. According to anti-transgender activists and lawmakers, Title IX protects the rights of cisgender women by preventing or banning trans athletes from competing. (The research is ongoing, and the science is still uncertain about any physical advantages transgender women might have over cisgender women.)

As of 2020, about half of U.S. states have passed laws that bar transgender girls and women, and sometimes boys and men, from participating in publicly funded educational activities in the categories that align with their gender identities. (Some of those bans are pending in court.)

Numerous international sports governing bodies have been tasked with establishing legally binding and equitable guidelines. The organizations that severely restrict transgender women’s and women’s participation, including World Aquatics and World Athletics, have required those who have undergone testosterone-driven puberty.

“I’m 110 percent frustrated,” said Mack Beggs, a trans man and former NAIA wrestler for Life University in Marietta, Ga. Competing in college, he said, “meant the world. It also helped me develop as a person and not just as an athlete.”

According to a spokesperson for the NAIA, no out-of-state transgender athletes are currently counted among the roughly 83,000 individuals who participate in its sports. The organization’s 2023-24 legislation permits trans and intersex athletes to compete in any gender category during the regular season.

Trans athletes who have undergone gender-affirming hormone therapy may compete in collegiate sports or single-gender sports in the gender category that aligns with their sex at birth in postseason competitions. Transgender individuals receiving gender-affirming hormone therapy may participate in the postseason if they have completed one year of treatment. Transgender men undergoing clinically prescribed, sex-affirming testosterone therapy cannot compete on women’s teams but may compete on men’s teams in the postseason.

Chris Mosier, the first openly transgender athlete to compete internationally and a transgender rights activist, referenced recent anti-trans rhetoric as a potential influence on collegiate sports governing bodies’ policies.

“The NAIA and NCAA, along with many other sport organizations, teams, and leagues, have been under attack by anti-trans groups and individuals who have made it their life’s work to harm transgender people,” Mosier wrote in an email. “A policy change at this time, without a robust process of engaging experts, athletes, and people with lived experience, is solely based on political pressure.”

About 40 openly transgender athletes are believed to compete in NCAA sports, Baeth said. Sixteen cisgender college athletes, both current and former, filed a lawsuit against the NCAA in March, demanding that it redistribute any awards given to them and that trans women be barred from competing in women’s events. According to the plaintiffs, by allowing transgender athletes to compete, the NCAA allegedly violated Title IX. Lia Thomas won the 500-yard freestyle at the 2022 NCAA Division I championships.

In preparation for the swimming championship meet, the NCAA most recently updated its transgender eligibility policy in January 2022.

The organization adopted a sport-by-sport approach that required athletes to adhere to rules set forth by the international governing body for their specific sport. That change is still being phased in. The next meeting of the NCAA Board of Governors is scheduled for April 25.

According to an NCAA spokesperson, “College sports are the premier stage for women’s sports in America, and the NCAA will continue to promote Title IX, make unprecedented investments in women’s sports, and ensure fair competition for all student-athletes at all NCAA championships.”

During a Final Four news conference Saturday, a reporter from Outkick, a conservative sports website, asked South Carolina women’s basketball coach Dawn Staley about her position on transgender athletes.

“I’m of the opinion that if you’re a woman, you should play

,” Staley said. “If you identify as a woman and you want to play sports, or vice versa, you should be able to play.”

This story is developing, and it will change.