(UroToday.com) The 2023 Society of Urologic Oncology (SUO) annual meeting held in Washington, D.C. between November 28th and December 1st, 2023, was host to a prostate cancer course. Dr. Stephen Freedland discussed the development of prostate cancer in transgender women, with this being an area of ongoing, active research. The objectives of Dr. Freedland’s presentation were to:

- Review the contemporary literature on prostate cancer in transgender women

- Discuss what is known thus far about PSA screening in this population

- Propose tips on providing patient-centered care for transgender patients

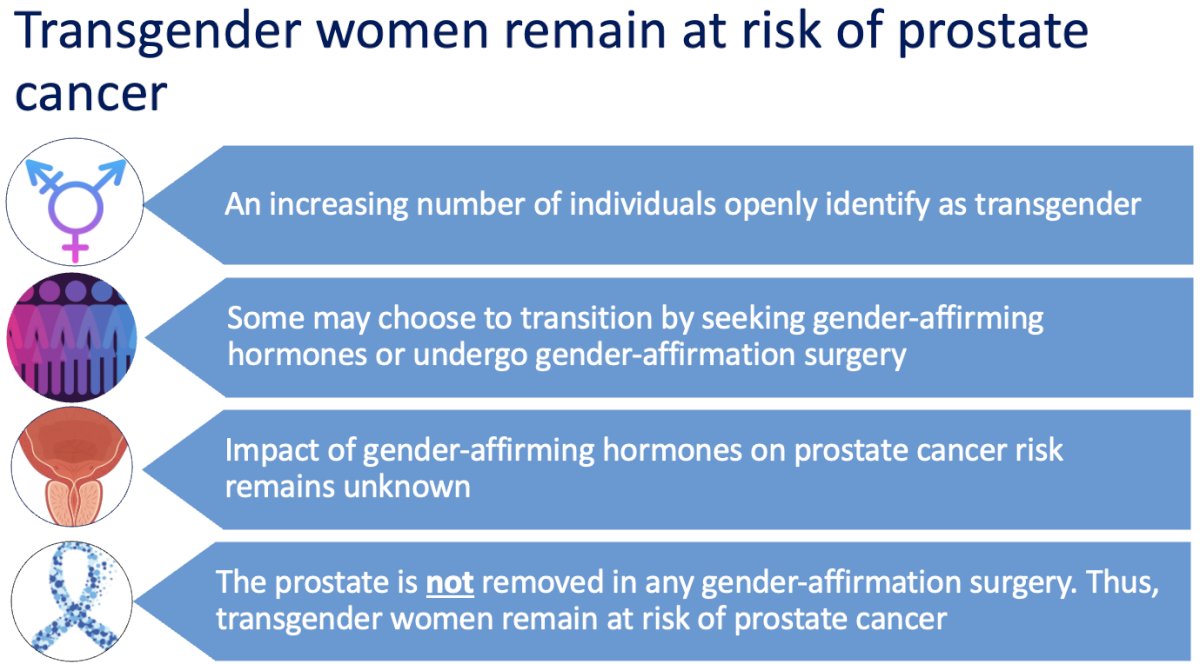

It is currently estimated that approximately 0.6 to 1% of the US population identifies as transgender. Despite significant ongoing marginalization and discrimination disproportionately affecting this group, an increasing number of individuals openly identify as transgender, and this number is projected to increase. Thus, it’s likely that all clinicians will care for transgender individuals at some point. There’s significant variety in terms of how patients transition – some may not be on any gender-affirming hormones or undergo any surgeries, while some transgender patients choose to transition with gender-affirming hormones or to undergo gender-affirmation surgery. Prostate cancer is a hormonally-driven cancer – while some forms of gender-affirming hormones may decrease the risk of prostate cancer, there is other data that those hormones may increase the risk for some forms of prostate cancer. Overall, this is an area of ongoing research, and the exact impact of gender-affirming hormones on prostate cancer risk remains unknown. Clinicians should be aware that transgender women retain their prostate regardless of whether they have undergone gender-affirmation surgery. Thus, transgender women remain at risk of prostate cancer and should still be considered for prostate cancer screening

Previous literature on prostate cancer in transgender women was limited to only 10 case reports and few other studies. The overall incidence of prostate cancer in transgender women remains unknown.

Given this tremendous lack of primary literature, Dr. Freedland and colleagues sought to conduct a national study describing prostate cancer in transgender women specifically focusing on prostate cancer characteristics at diagnosis, and to estimate the number of cases of prostate cancer per year in this population. To accomplish this, they performed a retrospective study of adults ages 18 and older between January 2000 and November 2022. Patients with both an International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) code for prostate cancer and an ICD code related to transgender identity were queried. Given that there is no specific ICD code for transgender identity, Dr. Freedland and colleagues used 13 ICD codes related to transgender identity that were previously determined to be both sensitive and specific for this condition.

A detailed chart review was performed to verify transgender identity and prostate cancer diagnosis details, including clinician notes, medications, gender-affirming hormone therapy use, PSA values, and prostate biopsy details.

They identified 155 patients who were confirmed on chart review to be transgender women with prostate cancer. Estrogen was by far the most common gender affirming hormone therapy used, and thus patients were stratified by their estrogen usage: 116 had never used estrogen, 17 had formerly used estrogen, and 22 actively used estrogen at diagnosis.

Overall, the median age at prostate cancer diagnosis was 61 years, most patients were White with only 8% Black, the median PSA at diagnosis was 6.8 ng/ml, and the duration of estrogen use was 32 months among estrogen users.

The investigators noted that the observed number of cases per year per 10,000 transgender women was less than half (14) of what was expected (13). To roughly estimate the number of cases per year, they used the median year of transgender identity entry into the medical record and a previous estimate of 10,000 transgender women within the VA and compared this to published rates of prostate cancer incidence among cisgender Veterans. Based on this, the expected number of cases was roughly 33 cases per year. The observed number of cases was determined to be about 14 cases per year.

What about clinical differences based on estrogen usage patterns? The median PSA density, a surrogate of prostate cancer aggressiveness, was highest for those on estrogen at diagnosis (0.31 ng/ml/cc versus 0.21 ng/ml/cc for never users). Of note, prostate volumes were comparable across groups, so this is a direct function of serum PSA levels.

Additionally, the highest percentage of Grade Group 5 disease was observed in patients on estrogen at diagnosis (29%). This is compared to only 12% for never estrogen users and 6% for former estrogen users. For comparison, approximately 16% of cisgender male veterans have Grade group 4 or 5 disease at diagnosis. For those with no prior estrogen use, Grade Group 1 – 2 disease was found in 71% compared to 56% of former estrogen users and 53% of patients on estrogen at diagnosis.1

Dr. Freedland noted that the most important findings from this work were, first, that prostate cancer does occur and is not as rare as published case reports may suggest. Second, and nonetheless, rates were lower than what was expected. Finally, though these numbers were very small, there were trends to suggest that transgender women actively on estrogen had higher rates of Grade group 5 disease and a higher PSA density, both of which suggest delayed diagnosis.

It is unclear if the observed lower rates of prostate cancer are due to underdiagnosis as opposed to a ‘true’ lower incidence in this population, or potentially both. There are several factors that may be at play here. These may include lower rates of PSA screening, lack of awareness of prostate cancer risk by both clinicians and patients, the suppressive effects of estrogen on prostate cancer development and biology, and, perhaps most importantly, that prostate cancer may ultimately be missed in transgender women due to misinterpretation of “normal” PSA levels in those receiving gender-affirming hormone therapies. PSA reference ranges are all set based on data from cisgender men, but transgender women on gender-affirming hormone therapy would be expected to have significantly lower PSA levels. Thus, a “normal” PSA value in a transgender woman on estrogen may actually be very concerning and warrant further evaluation.

What about PSA screening in transgender women? There are currently no guidelines on PSA screening for transgender women from any of the leading organizations. However, it is recommended that the same screening principles that apply to cisgender men be applied to transgender women. So, this should start with an assessment of a patient’s risk factors, including their age, race, and family history. The most important point to highlight is that all transgender women (including those on gender-affirming hormones or who’ve undergone gender-affirmation surgery) should still be considered for and counseled on PSA screening. For transgender women who are on gender-affirming hormone therapy, it’s important to be very careful with PSA interpretation and if there is any concern to refer patients to a urologist.

How can healthcare practitioners provide patient-centered care? Dr. Freedland highlighted that this begins in the waiting area before a patient has even been seen – it is important to create an environment that is inclusive. Examples include making sure that the art in the waiting area is gender neutral. Educating the team and the staff on the use of chosen names and pronouns can help prevent misgendering patients.

Another example is to make sure intake forms use affirming language and to ask patients what anatomical terms they are okay with and what their understanding of their anatomy is. Dr. Freedland recommends centering discussions around anatomy and not around gender, with this being a key point. We need to reframe our thinking about prostate cancer so that it’s not a “male” cancer but rather a cancer in people with prostates. When mistakes happen, we should apologize and correct them. Finally, by being an ally to this community and participate in outreach and community events.

As clinicians, we are at the forefront of transgender care – it is up to us to change the narrative on prostate cancer in transgender women, to work together to increase awareness among both patients and other clinicians, and to provide the best possible care for these patients

Dr. Freedland concluded with the following take home messages:

- All transgender women, regardless of gender-affirming hormone therapy usage or gender-affirmation surgery remain at risk of prostate cancer

- For those who are age appropriate, Dr. Freedland recommends engaging in shared decision-making about PSA screening

- Remember to interpret PSA values carefully for those who are on gender-affirming hormone therapies and that a “normal” PSA value that is within reference ranges may be concerning in a transgender woman on gender-affirming hormones

- If there is any concern about a PSA value being potentially elevated, refer patients to a urologist so that they can undergo further assessment

Presented by: Stephen Freedland, MD, Professor, Department of Urology, Cedars Sinai Hospital, Los Angeles, CA

Written by: Rashid K. Sayyid, MD, MSc – Society of Urologic Oncology (SUO) Clinical Fellow at The University of Toronto, @rksayyid on Twitter during the 2023 Society of Urologic Oncology (SUO) annual meeting held in Washington, D.C. between November 28th and December 1st, 2023

References:

- Nik-Ahd F, De Hoedt A, Butler C, et al. Prostate Cancer in Transgender Women in the Veterans Affairs Health System, 2000-2022. JAMA. 2023;329(21):1877-1879.