Who was the first trans man whose name you knew? If there was a moment when you became aware that trans men existed, and a particular public figure whose name you associate with that realization, who would it be?

As an experiment, last week, I posted on Twitter and Bluesky, asking people to answer this question. To their credit, a lot of people named a friend or a partner. But overwhelmingly, those who didn’t gave me one of three names: Brandon Teena, whose murder was the subject of the 1999 movie Boys Don’t Cry; Chaz Bono, the son of the singer Cher, whose transition was the subject of a documentary (and some Dancing with the Stars episodes) in 2011; and, most regrettably, Buck Angel, who started out as a wholesome pornographer before losing his virtue to the corrupt and depraved world of TERF advocacy.

“Transmasculine erasure” is a talking point that’s been repeated often enough to become cliché. Trans women are hyper-scrutinized; it puts them in danger, but it also means that more people pay attention to them. Trans men tend to fly under the radar. The dominant culture regards us with baffled incomprehension—when it acknowledges that we exist.

This makes collecting trans men’s history remarkably difficult. Important figures are forgotten, overlooked or simply never given much recognition in their lifetimes. It also stymies trans men’s self-recognition: “You can’t be what you can’t see,” to quote the old saw about representation. If the only life paths the culture offers to people like you are death, infamy or Dancing With the Stars, it’s hard to see a way forward.

Yet trans men did exist before the late 1990s. The trans men who have been authors, activists, educators—trans men who have advanced our knowledge of gender and made the world a better place—are out there. We just don’t hear about them. For example: I had received dozens of answers to my “first trans man” question before someone mentioned Jamison Green.

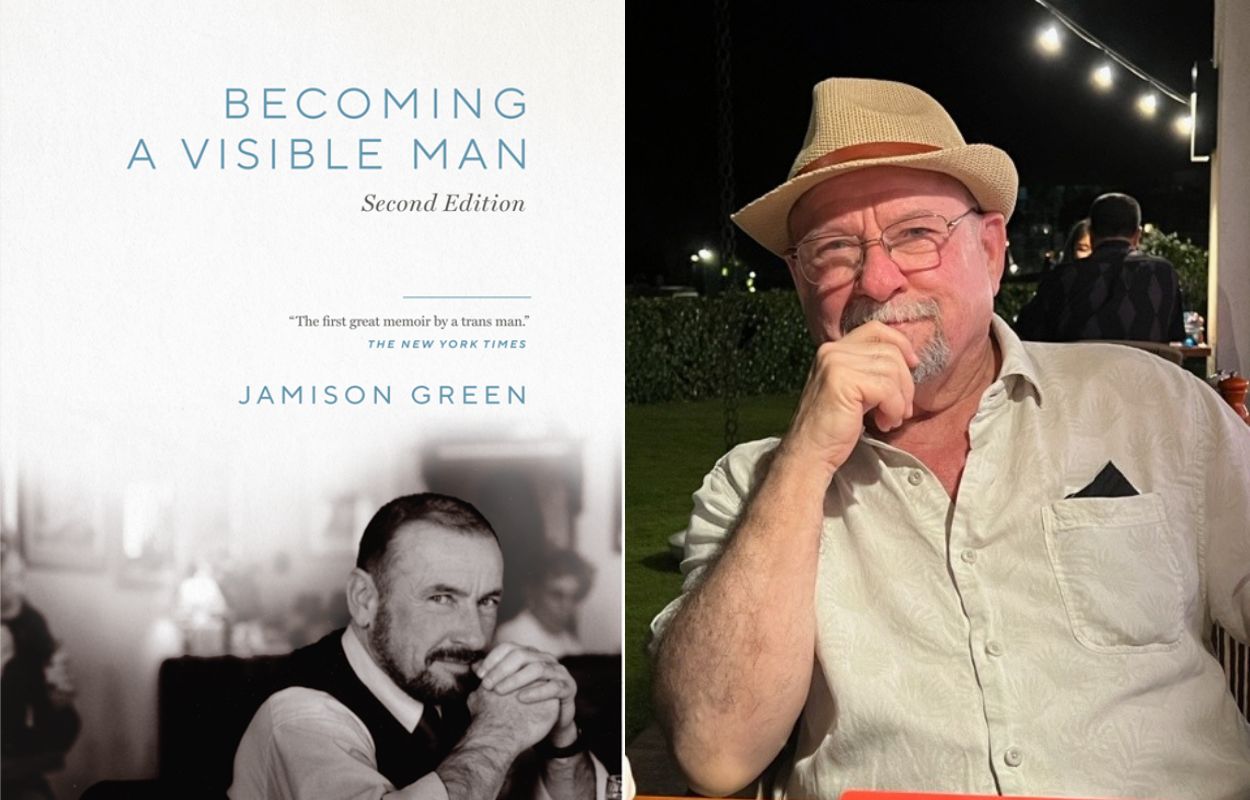

Jamison Green was the second-ever head of FTM International, the oldest U.S. organization for trans men; he inherited the title from the organization’s founder, Lou Sullivan. He’s a lifelong advocate for trans people’s medical care, who—among other things—helped to rewrite the WPATH guidelines for transition care to include trans men. He’s the author of what Jennifer Finney Boylan has called “the first great memoir by a trans man,” Becoming a Visible Man, published in 2004. He was one of the very first trans men to take on the job of being a public ambassador for the trans community. Before any of that, though, he was just another guy who had never seen a trans man.

Green was born in 1948 and adopted into a loving but conservative family in California. He was never pressured to present in a feminine way at home, he tells me, but in the 1950s, you wore a skirt to school if you were assigned female, and that was that. Even so, he had such a strong sense of himself that adults often took him for a boy in a dress, which is what he was. His first glimpse of his own possibility, as he writes in Visible Man, was seeing Mary Martin in a television broadcast of Peter Pan. Watching Martin as Peter, he thought, “If she can be a boy, so can I.” By the end of the broadcast, he had noticed that Peter was being a real jerk to Wendy: “I’ll be a much better boy than she is,” he remembers thinking.

The word “transgender” was not on his radar. In the mid-1960s, his first girlfriend suggested that he would be happier if he got a “sex change”; he recalls being horrified, and telling her that “those people” were crazy. Then, in the mid-1970s, he met his first trans man.

“He and his girlfriend went off to New York so that she could become a Broadway star,” Green says. “In a green room he saw a flyer that they were looking for 12 trans men, or ‘FTMs,’ in the language of the day, to go through a program at Oregon Health & Science University.”

Green’s friend (whom Green is keeping anonymous out of respect for his privacy) called the number on the sheet and got enrolled in the program: “Next thing you know, he’s taking testosterone there in New York. And six months later, he’s coming back to Oregon so he can have top surgery. They helped him and his wife get sperm so that they could have children.”

Green’s friend wrote to him when he started testosterone, saying that Green would “really like it.” When he came back to Portland, where Green was living at the time, Green could clearly see that transition was working: “He was really a much happier person, and he wasn’t so ashamed of himself as he had been. He just kind of slunk around before.”

Yet it was not all good news: “He said, ‘Now I get the respect that I deserve,’” Green recalls. “I was like, ‘You know, women deserve respect, and masculine women or feminine men also deserve respect. This whole assimilationist thing is not where I’m coming from.’”

Green’s friend went stealth soon after transition, and has remained so ever since: “He still has not told his adult children that he’s trans,” Green says.

This was the standard for trans men when Green came out in the 1980s—they were instructed to disappear and blend in as much as possible, which meant upholding the most limiting stereotypes of their gender. It was radical—in fact, unheard of—to even publicly be a trans man, let alone a man who questioned traditional masculinity and his own place in it. Under those conditions, Green didn’t see a path forward.

The man who changed things, for Green and for the world, was Steve Dain. Dain had been a girls’ gym teacher at a San Francisco Bay Area high school; he lost his job when he transitioned, and chose to fight the termination, thereby becoming a local news story. Dain’s high visibility and eloquence soon made him a mentor for many trans men in the Bay area, including—most famously—Lou Sullivan, founder of FTM International.

To Green, Dain also represented a more livable version of masculinity—one not tied to patriarchal norms, where “becoming a man” didn’t require being a traditional, straight man who purchased “respect” at the cost of a relationship with his own kids. “He did not [transition] because being a man was somehow better than being a woman, but because it was the only thing he could do to be himself,” Green wrote in Visible Man. “It was about telling the truth, not about hiding.”

Green met Dain for the first time at a Bay Area gathering hosted by Sullivan. It was Sullivan, even more than Dain, who publicly broke the mould for what a trans man was allowed to be. Sullivan was gay, which (at the time) was disqualifying for HRT and surgery; Sullivan campaigned relentlessly for the rights of gay trans men to access medical transition, and became the first openly gay man to do so in 1979. Sullivan also resisted the cultural imperative for silence, writing a newsletter and a guidebook, Information for the Female-to-Male Crossdresser and Transsexual, directed explicitly at overcoming transmascs’ cultural illegibility: “The professional community acknowledges the female-to-male makes up an even 50 percent of the total transsexuals,” Sullivan wrote in the guidebook. “However, even now, female-to-male transvestites are said to be non-existent. Maybe because they are less visible and vocal, more closeted and guilt-ridden.”

Last but not least, Sullivan worked to create support groups and in-person gatherings where trans men and transmasculine people could actually meet each other face to face, often for the first time. “The whole reason [Dain] transitioned was to become a man and fit in with men,” Green tells me. “He had no desire to build a transgender community. Lou wanted community.”

It was that choice to be a community that led to the political mobilization of trans men as part of the queer liberation movement. In the pre-Stonewall era, the trans men who had the luxury of being out were rare and isolated cases, and often came from extremely privileged backgrounds that helped mitigate their gender: Eccentric millionaire Reed Erickson, who funded much early medical research on gender-affirming care, or British aristocrat Michael Dillon, a doctor whose 1946 book Self: A Study in Ethics and Endocrinology was one of the first books on trans medical treatment. The rest either went stealth (like jazz musician Billy Tipton, whose trans status was discovered only after his death) or never got to transition at all (like civil rights leader Pauli Murray, who spent much of their youth looking for doctors to prescribe them testosterone, then stopped when they became a nationally known figure). The idea of trans men as a coalition—a group of ordinary people organized around their shared political interests, gaining strength from numbers—was new, and it largely took shape in the lineage that ran from Dain to Sullivan to Green.

Sullivan died of AIDS in 1991; he chose Green to lead FTM International after his death. In the nine years that Green oversaw the organization, the Bay Area exploded with activism, art and literature from trans men. Again: the history of contemporary trans activism is short. Many of the texts we regard as foundational are less than thirty years old. Two of the earliest books on trans men —Loren Cameron’s Body Alchemy, 1996 and Henry S. Rubin’s Self-Made Men, 2003—emerged out of the Bay Area in the 1990s. You Don’t Know Dick: The Courageous Hearts of Transsexual Men, a 1997 documentary that some people mentioned to me as their introduction to the subject, also draws from that scene, and Green is one of its subjects. (You can get a sense of the era from the fact that, at one point, Green refers to sending “an electronic mail.”) Transmasculine authors Patrick Califia and Max Wolf Valerio were part of the scene, as were around half of the other trans men whose names you might know.

Green had originally wanted to be a novelist, and he would have been poised to take advantage of this renaissance. The book he did write—Becoming a Visible Man—is canonical. Instead, Green spent this era doing the work of organizing and leading, which meant a lot of unglamorous, hands-on work with the details of healthcare policy, and a lot of time in rooms with cis people, explaining how it was possible for him to even exist.

It’s almost impossible to overestimate how much extremely basic information Green had to cover for his audiences of that period. Sometimes, he writes, people would be told in advance of his presentations that “a transsexual” was coming to speak to them; when they saw him walk into the room, they were visibly disappointed, figuring that the transsexual couldn’t show up. Other panels, supposedly convened to discuss the needs of trans men, were instead spent explaining to the audience what trans men were.

Green’s own activism was practical and granular, focused largely on medical care. “I was going out and speaking to psychologists, psychiatrists, dentists, lawyers,” he says. “You know, unless people find out that we exist, how are we going to be safe? We can’t be safe as long as we’re disguised. We can’t be safe as long as we’re invisible. At some point you’re going to be vulnerable, at some point you’re going to get sick, or you’re going to get in an accident, and people are going to be just shocked by you. They’re not going to take good care of you.”

Green worked to illuminate the ways trans people are treated in medical settings: “Trans broken arm syndrome,” the phenomenon in which doctors blame every unrelated illness a trans person might have on their transition, was first identified by Green. He lobbied employers and local government to ensure that insurance plans covered medical transition. His most high-profile contribution to trans care, working on the WPATH guidelines, which set the standards of trans care and thereby determine how and when trans people can transition, is one for which he was initially not credited at all.

As Green describes it, the WPATH revision effort was being protested by trans men, who noted that the guidelines were only written to cover trans women’s medical care. Green was part of the crowd of protesters, and he was also a recognizable face, which led to him being selected to advise the board pretty much by fiat. After the protesters had beaten down the doors and charged the room where the WPATH committee was meeting, Green says, “The guy who was in charge of the revision effort pointed at me in the audience and said, ‘All right, you can look at the draft over and give us some feedback.’ Me? I wasn’t even a member of the organization.”

Nonetheless, Green went over the proposed guidelines with a group of trans men, and wrote a 12-page document giving feedback on things like hysterectomy (which trans men sometimes require for medical reasons other than gender, but which doctors could withhold simply because they were trans). He stayed up for 24 hours straight to meet the deadline. When the WPATH revision came out, it contained none of his suggestions, but it did have his name on the front— essentially, trying to avoid activist critique by saying that a trans man had looked at it.

In 1999, when the WPATH performed its next round of revisions, Green’s changes were incorporated, but his name was nowhere to be found. “Did I get any credit for that?” Green says, sounding audibly frustrated, before biting it back. “You know, that’s okay. The most important thing was to get these changes.”

But it wasn’t okay, and Green should probably be angrier about it than he is. Green was eventually admitted as a member of WPATH in 2002, and was named president in 2011, a post he held until 2018. Still, it’s hard not to see this early episode as a metaphor for Green’s career writ large. In the post-social-media age, when we tend to confuse queer “leaders” with queer influencers, Green’s actual leadership is criminally easy to overlook, even though our health and safety depends on it. Green has never been private, but the vast majority of his work has not been about building his brand. He put the work first. He put the community first. He put other people first, and the world used that as an excuse to pretend he was never there.

Rocco Kayiatos started to realize that he was trans as a teenager. It was 1999 or early 2000, he says, and Google didn’t really exist: “I remember searching on Ask Jeeves for literally anything related to trans men.”

He was living in San Francisco, and was part of the queer poetry scene, having toured with Sister Spit; he was able to meet trans people that way, and the poet Max Wolf Valerio became a friend. Still, Kayiatos says, he struggled to put himself together: “The reaction that I got was really rough,” he recalls. “I felt like I couldn’t really be a man, one, because of insecurity around my own transness, but then two, because culturally, I got so much pushback from people that I loved about how shitty men were and why would I ‘want,’ quote unquote, to be a man.” The trans men he read often seemed to be guilty or defensive: “I never read a book by a trans guy about their experience that wasn’t somehow written in a way that’s like, almost an apology for being a man.”

Then he read Green’s memoir. “It’s just the most profoundly gentle and loving and compassionate offering to healing masculinity, that’s so timeless,” Kayiatos says. “It’s still relevant and advanced in the present day … for me, when people are listing the must-reads about transmasculine people, places or things, if they don’t start with James’s book, I just think, ‘You missed it.’ Because his book is the starting point.”

Kayiatos asked Green to come and speak at the first Camp Lost Boys, a yearly retreat for trans men that has been running since 2017, and they’ve been close ever since. “He’s been like a father figure and a mentor to me in a really profound way. I just feel really grateful to have access to someone who has done so much work,” Kayiatos says.

In fact, it’s hard not to be struck by a sort of family resemblance in the two men’s stories. Though Green came out thirty-something years before Kayiatos, both men felt like a new phenomenon, and could only come into their own once they saw someone else model a version of masculinity that they could live with. Jamison Green found it in Steve Dain; Rocco Kayiatosfound it in Jamison Green; now, Kayiatos—who was one of the first public trans men whose name I knew; whose magazine, Original Plumbing, was for a long time the only magazine aimed at trans men, and who still runs Camp Lost Boys, where trans men still gather and meet each other face to face—has been that guy for who knows how many others. This, maybe, is what it means to have a history and a heritage. This story about non-belonging is how trans men belong.

At the very least: the problem of identification, of how to write yourself into the picture of manhood when the culture contains no image of you, seems to recur for trans men in each generation. In my early twenties, when I first started to realize I was trans, what little I knew about trans men was based on stereotypes: they all started out as butch lesbians, they all dated women exclusively, they were all hypermasculine uber-tops who expressed nothing but traditionally macho interests and values from the moment they left the womb, and none of them were anything like me. I used those stereotypes to tell myself that I was not, and never could be, a man; my desire to be on testosterone and my culture’s idea of masculinity didn’t line up.

Now, in 2024, I can see trans men who are gay, who are shy, who are femme, who are feminists—and those men have made me possible and thinkable to myself. But there is still someone out there who doesn’t know he has the right to call himself a man. There are, in fact, many someones. There is no one right way to be a trans man, because there is no one right way to be a man, period; we will always need more and more and more visible trans men, until our image of transmasculinity is just as varied as masculinity itself is, and everyone can see the guy who looks like the guy he’s supposed to be.

We also need history, because without history, we are stuck on the hamster wheel of self-definition, each new generation of trans guys struggling to come to grips with our identity as if we were the very first. The circular, frustrating, often half-baked nature of transmasc discourse, especially online, is a pain point for many of us, but it’s also the inevitable result of guys who have only been out for a few years trying to come up with answers for other newly out guys, often with nothing but previous internet conversations for reference.

“I’ll find threads where these young guys are trying to answer pretty advanced questions for each other, and then maybe every once in a while, someone will pop in and be like, ‘Well, I’ve been on testosterone for eight years, so, as your elder,’” says Kayiatos, who has been out for 24 years. “And I’m just like, ‘Oh, my God, we’re so disconnected.’”

In the absence of real elders and institutional memory, we lead ourselves round in circles, repeating a history from which we did not learn, because we were never taught. It is largely thanks to Jamison Green that there is such a thing as a transmasculine community. Those of us who feel invisible and isolated in the present day—and many trans men, maybe even most of us, still do feel that way —could do worse than to look to him.

“James celebrated his 75th birthday at this last camp,” Kayiatos tells me. “We had a big surprise party for him … and he cried and had this real moment of just having this emotional outpouring. When I looked around the room of 125 younger trans men, seeing this, there’s so many layers to that. Who this man is, what he’s done for all of us, for us to exist in a space like that.”

Green is writing a novel now; he is doing the work he feels passionate about, after doing decades of work for others. But it is already time, and past time, for us to know his name. Generations of trans men asking the same questions means generations of answers. Until we avail ourselves of all those answers, we will never really have the full picture of who we are.