Twenty years ago, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) declared that fairness in women’s sport did not matter – just not in so many words. In 2003, even before the IOC permitted women to play rugby, to box or ski-jump at the Olympics, it was apparently determined to find a place in the games for what it then called male-born transsexuals – that is, men who identify as women and have undergone genital surgery.

The fact that male athletes enjoy considerable physiological advantages over females was considered, but duly ignored. An adviser to the IOC, Louis Gooren, had studied the effects of female-hormone treatment on transitioning males. He reported that although hormone therapy did decrease male athletes’ total muscle mass, it still remained considerably larger than it would be for the average female athlete. He told the IOC: ‘Depending on the levels of arbitrariness one wants to accept, it is justifiable that reassigned males compete with other women.’

At this early stage, to participate in the female category in the Olympics, transsexual males had to have had their testes removed (known as ‘gonadectomy’) at least two years before competing. They also had to have a female legal status and have hormone levels in line with female levels. As only one in 12,000 males has gender dysphoria, it was expected that the number of transitioned males wishing to compete as females would be negligible.

You might wonder why such a policy was needed if hardly anyone would benefit from it. This is one of the contradictions at the heart of the trans question in sport. The IOC’s answer was that there would be plenty of transgender athletes wanting to compete in women’s events, but not at the elite level. In 2005, two IOC committee members wrote: ‘Inevitably there will be transgendered athletes, such as [tennis player] Renee Richards, who will be competitive at a high level, but most will probably wish to compete only at a masters level or at local and regional events.’ Why the IOC felt it right to encourage unfair competition for women at masters, local or regional levels is not clear. But this casual disregard for non-elite sportswomen is a recurring pattern.

Ten years after that IOC decision, policy guidance was issued to sports national governing bodies (NGBs) in the UK by the Sports Council Equality Group. (Most sporting matters are devolved to the home nations, but questions of equality are handled at the UK level.) The 2013 policy document, ‘Transsexual People and Competitive Sport’, acknowledged input from five groups representing trans-identifying people, including the Gender Identity Research and Education Society (GIRES) and Stonewall Scotland. No women’s groups were mentioned.

It was clearly an activist document, encouraging sports bodies to ‘consult and build relationships with transsexual people and associated organisations’. A list of such organisations was helpfully included. The document also claimed that ‘biological sex is assigned at birth, depending on the appearance of the infant’ – a common, but nonsensical, trans-activist trope.

Crucially, no one in charge at any of Britain’s sporting bodies seemed to have realised that a fundamental change to eligibility for female sport was being made. And it was being made without even considering the impact on females – never mind consulting them.

How junk science led to self-ID

Separate male and female sport has never been controversial. It’s written into UK law. Section 195 of the Equality Act 2010 says it is lawful to separate sport by sex where necessary for reasons of fairness and / or safety. It even states explicitly that trans people can be excluded for the same reasons.

The 2013 guidance turned Section 195 on its head. It said that ‘NGBs should treat a transsexual person as belonging to the sex in which they present (as opposed to the biological sex they were born with), unless this might give the transsexual person an unfair advantage or would be a risk to the safety of competitors, which might occur in some close-contact sports’.

This ignored the clear legal position that we can organise sport by sex, regardless of claimed or perceived gender. And it redefined inclusion to mean ‘inclusion in the category of your choice’. The only demand it made of male athletes who want to compete alongside women was that they should suppress their testosterone levels, though it gave no scientific rationale for this. Despite all these issues, as it came from the Sports Council Equality Group, this policy was widely adopted by British NGBs without question.

Two years later, the IOC revisited its trans policy. A legal case in France had called into question whether someone needed to have genital surgery for them to be recognised as their desired sex. This case had nothing to do with sport specifically, but the IOC took an interest anyway.

The IOC consulted medical physicist Joanna Harper, who had transitioned in middle age. Harper was a recreational distance runner who had noticed his running times getting slower. He asked around and collected similar data from seven other trans runners, and then published a paper of the findings. The eight athletes recalled their past running times and noticed they had lost 10 per cent of their speed on average since transitioning. That’s roughly the difference between men and women of the same age and standard in distance running. And so Harper declared that testosterone suppression post-transition should be enough to allow males to compete fairly against women.

Harper’s paper is about as far from proper science as it gets. One of the runners Harper consulted had actually improved his performance since transitioning, but his data were left out. All the others had most likely slowed down with age, but this was not factored in. Nor were other confounding factors, like injuries or lifestyle changes. Nonetheless, thanks to this paper, the IOC decided that testosterone suppression would be sufficient for allowing males into women’s events at the Olympics – the pinnacle of sporting competition.

In truth, a male athlete’s testosterone levels are largely irrelevant to this debate. Testosterone suppression cannot reverse the changes wrought by male puberty, which is where most of the physiological advantages that men enjoy come from.

Nevertheless, the IOC duly updated its guidance and the UK’s sports councils followed suit. As it turns out, these changes had their biggest impact on non-elite sports. In practice, no one has any idea of their testosterone levels at any given moment and most amateur athletes do not regularly measure their levels. This meant that the male population eligible to compete against women was broadened from just a handful of athletes – that is, those who had undergone surgery and had legally changed their sex – to anyone who merely claimed to be the other sex.

Some sports, like cricket and tennis, dispensed with testosterone-suppression requirements altogether, arguing that anyone should be accepted as whatever they say they are. The UK’s Lawn Tennis Association acknowledged in 2019 that ‘there may be some concerns about fairness in the women’s and mixed game’. But not to worry, explained the association:

‘Our policy assumes that transwomen (male-to-female trans persons) wishing to compete in mixed or female-sanctioned tennis competitions do so with the best of intentions and with no intent to deceive about their status to gain any competitive advantage. Accordingly, you should accept people in the gender they present and verification of their identity should be no more than that expected of any other player.’

The best of intentions. So that’s okay then. The Lawn Tennis Association added that any woman who feels uncomfortable sharing the changing room with males should simply get changed at home.

The silencing of female athletes

Now that the real-life consequences of these unfair policies are emerging, we need to understand the root cause.

The main problem is that the whole issue was framed wrongly from the start. It was positioned as being about trans people rather than about who should be eligible for female competitions. Trans-advocacy groups were consulted on these changes, but women’s groups and female athletes were not. Policies were, in effect, written by trans lobby groups. Even now, despite the considerable public backlash against ‘trans inclusion’, some policies say that anyone who feels discomfort with men competing in women’s sports needs to educate themselves. Normal boundaries have been redefined as ignorance and prejudice. As Arne Ljungqvist, an attendee at the 2015 IOC meeting, put it: ‘It has become much more of a social issue than in the past. It is an adaptation to a human-rights issue.’

Most of us might have thought that getting to compete in the Olympics was far from a human right. But years of lobbying by trans activists succeeded in establishing the idea that trans identities need to be validated above all else. Because trans people need to believe they have actually changed sex, apparently the decent thing for the rest of us to do is to act as if they really have. While this is possible in some situations, sport is clearly an area in which biological sex matters – where the demand to treat a man as a woman is completely unreasonable.

People who work in sport are all too aware of the differences between male and female athletic performance, so what were they thinking? I have to conclude that many of them were not thinking at all.

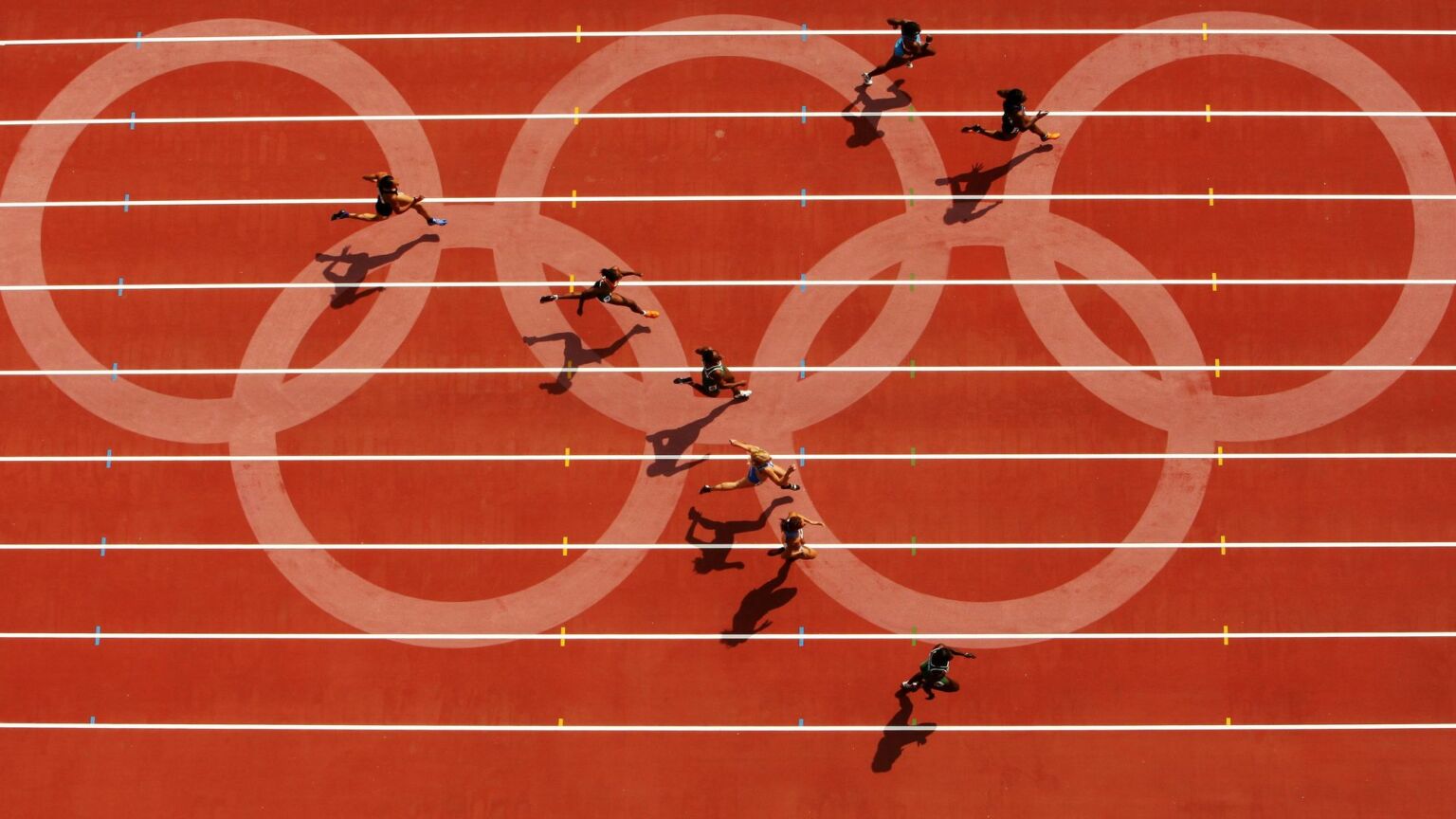

It is precisely this absence of thinking that allowed a 43-year-old, out-of-condition male, Laurel Hubbard of New Zealand, to get to the final of the women’s weightlifting in the Tokyo Olympics in 2021. The average age of the other finalists was 24.

In Tokyo, Hubbard didn’t manage to complete a lift and didn’t make it on to the podium. All the same, in a post-event press conference with the three women who had actually won the medals, an excited male reporter gushed: ‘There was a historic night here with Laurel Hubbard competing as the first openly transgender [athlete] in an individual event. I was wondering what you felt about that and what you felt that it took place in your sport.’

A full eight seconds passed before any of the athletes responded. Chinese gold medalist Li Wenwen and British silver medalist Emily Campbell didn’t move. American bronze medalist Sarah Robles slid her facemask down, sipped her water, leaned into her microphone and said: ‘No, thank you’.#Nothankyou quickly trended on Twitter.

Robles must have known that she would not get away with making any comment on Hubbard’s presence, other than to say she welcomed it. Her response became symbolic of how women in sport have been gagged on the question of transgender inclusion.

Campaign group Fair Play for Women, where I am director of sport, has been pointing out for years that so-called trans-inclusion measures are leading to the exclusion of women and girls. Across most sports and at all levels, we hear personal accounts of how having to compete against a male, or share changing rooms with a male, is turning women and girls away from sport. For a long time, we had found very little media interest in reporting these stories. Sports bodies weren’t hearing them either, because the inclusion of trans-identifying males on their own terms had become an article of faith.

Anyone who suggests there is a cost to all this, which is borne exclusively by women, is quickly shushed, shouted down or shown the door. Despite not tracking the impact of their trans policies, many British sporting bodies insist that the effects are minimal. Even when World Rugby restricted women’s rugby to female-born players on safety grounds in 2020, the UK home nations did not follow suit. British Olympian Mara Yamauchi tells me: ‘I have been contacted by many people who have been negatively affected by this, females who have lost titles, prizes and records to males and been dismissed and belittled when they have raised complaints.’

Is the tide finally turning?

Prompted by NGBs, the Sports Council Equality Group finally reviewed its trans-inclusion guidance in 2021, this time commissioning experts in sports medicine. The new guidance stated that: ‘The inclusion of transgender people into female sport cannot be balanced regarding transgender inclusion, fairness and safety in gender-affected sport where there is meaningful competition. This is due to retained differences in strength, stamina and physique between the average woman compared with the average transgender woman or nonbinary person assigned male at birth, with or without testosterone suppression.’

In other words, allowing males in women’s categories is unfair and sometimes unsafe. Yet even this new guidance was not enough to prompt a rush of policy reversals from sports governing bodies.

The tide only really began to turn in March 2022, when a six-foot-four male swimmer calling himself Lia Thomas became a US national champion in women’s collegiate swimming. When competing against men, Thomas finished 554th in the 200-yard freestyle in the national college rankings. Yet after his transition, he was able to beat the times of three women who had won Olympic medals in Tokyo.

The following month, British Cycling had its own Lia Thomas in the shape of another very tall male, Emily Bridges – a cyclist good enough to make the women’s national team, though not the men’s. Bridges’s stated intention to win selection for the 2022 Commonwealth Games triggered a revolt among the elite GB women. A quick policy change was organised with UCI, the international cycling governing body. This required male athletes to undergo 24 months rather than 12 months of testosterone suppression, ruling Bridges out.

Then, in June last year, World Aquatics changed its policy to allow only those trans swimmers who have not gone through male puberty into women’s races.

The media coverage of Thomas and Bridges brought the issue into the mainstream and forced the hand of numerous governing bodies.

However, there is still a huge task ahead to restore fairness in sports. Since the new Sports Council Equality Group guidance was published, Fair Play for Women has met with more than 60 sporting bodies across the UK and internationally. Some have rolled back their misguided policies, but many are still equivocating. They are ignoring the personal testimonies of female athletes, and refusing to look squarely at the evidence.

The fact is that the presence of just one male is enough to disrupt women’s sporting events, as shown by the recent story of the Sheffield and Hallamshire women’s football league. Several teams have refused to play against Rossington Main Ladies, in protest against its fielding of trans player Francesca Needham. Needham was involved in an accident, which left one female player with a season-ending injury.

It is not just the woman who was injured who has been affected here. It is also the woman in the trans player’s team who has lost her place on the pitch. It’s the women on that team who are worried about getting hurt in training, and who have to share a changing room with a male. It’s also the players in the other 11 teams in that league – around 150 of them, some as young as 16 – who know they can’t tackle a male player without risking injury, and who are forfeiting matches because they do not want to participate in something that makes a mockery of their skills, their commitment, their game. Yet, so far, the Football Association (FA) has had little to say about this scandal.

What is stopping the FA, which claims to want to grow the women’s game, from taking action? Some sports bodies say they have to include transgender women (ie, males) because not to do so would be to deny their identities. But sport has never been organised around people’s identities. It is objective factors like sex and age that matter.

Other NGBs are afraid that trans-identifying players will sue them. But, once again, the law very clearly allows for sex separation in sports. (Admittedly, defending a legal action can still take up enormous amounts of time, money and energy, even if you win.)

Many sporting bodies seem to think they can compromise. They recognise the need for fairness at higher levels, but they want to be ‘inclusive’ lower down. Having let the intruders run all over the house, they want to try to limit them to the ground floor. But most sports are not elite. The majority of sport happens in and between clubs, not in professional leagues.

This reluctance to say a hard No to males in female categories comes with an unstated assumption – that female players can and should tolerate some discomfort and unfairness. Just like the IOC of 20 years ago, these sporting bodies are telling women that their needs don’t matter as much as those of trans-identifying males.

The exclusion of women

There are problems in recreational sports, too. Women-only swimming sessions, gym and yoga classes are promoted as a way to encourage women to be active, since we know that some women avoid mixed-sex activities for religious, cultural or personal reasons. But now women can’t be sure that if they attend a ‘women only’ event there won’t be a male in the changing room, or in the pool.

British Cycling runs guided rides for all, where everyone is welcome. It also runs Breeze Rides, billed as women-only events, because it knows there are many reasons why women may want a male-free event. Nevertheless, it insists those rides welcome ‘trans females and nonbinary individuals’ and it encourages males with a transgender identity to become Breeze Ride leaders. If your starting position is that transwomen are women, perhaps this makes sense. But to the women who think they are choosing a male-free event, it can come as a shock to find male participants, or even a male ride leader who cycles faster than everyone else.

The end result is that many women self-exclude – from Breeze Rides, from the gym or pool, from football and other sports. ‘Inclusion’ policies are driving women and girls out of the very category that was created to enable female participation. As one woman who gave up football after the experience of competing with and against trans-identifying males points out, the great efforts that have been made to make trans players feel safe and included have left her feeling ‘unsafe and excluded’.

Another says: ‘I made the choice to self-exclude because of the unfair advantage my team had; other women have done so because of shared changing facilities or the fear of getting injured on the pitch. There are also a number of young Muslim women in the league who may have had to overcome cultural barriers to join – and we shouldn’t forget about them… women deserve a level playing field.’

One parent told me about a national lacrosse weekend tournament, in which a ‘trans girl’ was playing in a girls’ team for 16- to 18-year-olds. ‘I was just surprised and concerned that a biological boy would be allowed to play in this age group given [the] possible physical advantages’, she said. Her questions about this to the national governing body went unanswered.

Elsewhere, young female cricketers are not only afraid to face male bowlers and batsmen – they are also afraid to question the England and Wales Cricket Board’s policy, in case it ends their chances of a career in the sport.

Women who do object have been called to meetings where the agenda includes ‘transphobia’ and ‘hate crimes’, making them genuinely afraid that the police might arrest them. A university student was warned by a friend that it would be ‘social suicide to make a fuss’. Complaining might also put her at risk of being kicked off her university course.

See you in court

Perhaps it will take a court win to force things to change. The first such legal action is now underway in pool, where there are few female events and clear male advantages (especially in the break shot). After males began showing up in women’s competitions, female pool players are now crowdfunding a legal case against pool’s organising bodies. One of the claimants, Jo, says: ‘It feels daunting. But we know we have support, and we have to do it. I see young women deflated before they’ve even started. I think if this continues they will stop entering competitions. If it continues it will destroy women’s sport.’

The betrayal of women’s sport has been long in the making. The fightback to restore fairness and sanity is only just beginning.

Fiona McAnena is director of the sport campaign at Fair Play for Women.