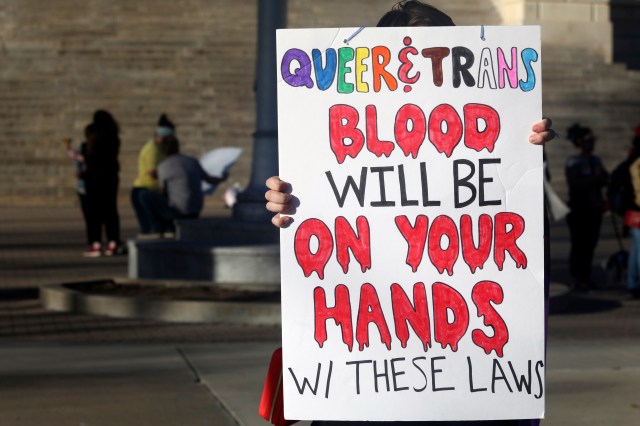

Last year, a staggering 22 states across the U.S. banned gender-affirming care for minors.

The conservative politicians behind this wave of legislation didn’t care that it went against the near-unanimous medical consensus that parents and doctors ought to be able to decide, on a case-by-case basis, whether puberty blockers, hormones, or other interventions are what’s needed for a given teen to flourish and live their life authentically. These lawmakers felt the consensus was wrong, that the government should take medical transition entirely off the table, at least until the kids grow up and can make “informed,” adult decisions. And in their eyes, there was a bonus: Removing the option of affirming care would surely lower the temperature in afflicted homes; it might well preserve the parent/child relationship until the threat hopefully passed—trans teens could no longer blame parents for not “allowing” them to transition. Parents were now free to say “There’s nothing I can do. You’ll simply have to wait until you’re older.”

Of course, in 2024, the mask has come off. Last year, Florida got things rolling with a law that made it impossible for adults to get new HRT prescriptions. And since Jan. 1, one state (Utah) has passed a sweeping bathroom ban that makes travel to the state functionally impossible for trans people; another state (Ohio) considered a medical regime that would make it essentially impossible for adults to get their meds; and at least 10 states have proposed laws to end all legal recognition of trans identities (i.e., the entire idea of transitioning would be erased from the legal code, making it impossible, for example, to change our driver’s licenses or birth certificates, use the correct bathrooms, or to run for office or use government services without outing ourselves as trans). Against this escalation, many trans teens justifiably worry that if they “just wait,” they might be waiting forever—banning adult access to gender-affirming medical care is now clearly the “endgame” of the right. At this moment, trans people’s ability to exist as trans people in the U.S. is more in doubt than it’s been at any point in the last hundred years.

For me, this poses a technical problem. My job is writing books for teens. I am trans; I write about and for trans teens in particular, and my stories have to assume that those teens have a life ahead of them. So, in this climate, what am I supposed to tell them and their parents about the future? I don’t have a crystal ball, so I can’t say how the legislative assault will play out—which bills will die in committee, which laws will be successfully challenged in court, which will be on the books for decades. Nor can I be certain about how long or how powerfully this anti-trans “backlash” will reverberate in public opinion or media.

But what I can say for certain is this: While conservatives may think they’re holding families together with these bans, they’re actually creating a situation where even the most tepid or fitful gender exploration is now a high-stakes event that has the potential to rip families apart. That’s because the moment a teen starts exploring their gender identity, their parents—right off the bat, before they can talk honestly with their kid or come to terms with what’s happening—have to make decisions about how they’re going to protect (or not protect) their family from becoming a victim of an uncertain and hostile legal regime.

It’s traditional for young adult novels about heavy social issues to include an author’s note giving information about how to find help if the reader needs help or support. If it’s about suicidality, it’ll be a link to a suicide hotline, for instance, or if it’s about queer/questioning youth, it’ll be a phone number for the Trevor Project.

I knew that when I was writing Just Happy to Be Here, my novel about a trans girl attending a fancy all-girls prep school in Washington, D.C., I wanted to write an author’s note that spoke very directly to the kids in question—instead of offering the hope of further support, I wanted to just straight-up give them some information they might need. And one of those major challenges faced by trans teens is uncomprehending or suspicious or just plain scared parents. To wit: My protagonist, Tara, lives in Virginia and isn’t on hormones or puberty blockers, because her immigrant parents are afraid of attracting the wrath of a nameless governor who campaigned for office on an anti-trans platform.

When I wrote the first draft of the book in 2021, Virginia’s governor was still a Democrat, and no state in the nation had yet banned trans medical care. My book was largely about the interpersonal dynamics of being a trans teenager. Contrary to portrayals on TV and in young adult novels, in real life, very few parents accept their child’s gender identity unconditionally. Parents are predisposed to distrust their kids’ judgement.

My 3-year-old daughter recently screamed at me because I couldn’t help her fly: “Make me fly for WEAL, FOR WEAL!” she said, when I lifted her up high. The idea of her telling me “I’m really a boy” is horrifyingly untoward. Parents can remember a time, not too long ago, when their kids were babies, and on bad days, their teens are still babies; it doesn’t feel natural to delegate medical decisions to them.

There’s really no test for transness, so ultimately you only have your trust in your child. It’s a tall order for parental types. Yes, the kid can and should go to therapy, but the therapist ultimately cannot be surer than the child themself can. Everyone is going to want the kid to be totally sure, absolutely sure, but even adults often aren’t sure! I was in my 30s when I finally transitioned, after waffling for a decade, and even then, I held off going on hormones for a year because of worries about health effects. But the moment I took them, I was sure that I was trans because my dysphoria finally cleared.

For a person with dysphoria, medically transitioning remakes the world. I got much more social, threw myself into the mothering role, and wrote three books in as many years. If your kid has dysphoria, you should want them to transition, because they will flower, open up, become smarter, happier. The only trick is: Do they really have dysphoria? Or something else?

You might say: Why not wait until adulthood to get intervention? But often, trans children are not happy. They are not flourishing. They are depressed, unmotivated, or anxious. For them, adulthood won’t truly arrive until they’re out from under the burden of dysphoria. And if a child does have gender dysphoria, then perhaps they could successfully transition in a few years (if adult transitioning remains legal in their state). But I can tell you from firsthand experience that the lost years have an impact on you. During those years I drank heavily, took drugs, binge ate, lost jobs and opportunities. The way I spent my pretransition years was not what most parents would wish on their kids.

Moreover, the current regime in some states doesn’t just curtail medical transition; there is also an attempt to block kids from even taking their first tentative steps down the road to transitioning. Recently proposed policy changes include prohibiting going by a different name, wearing cross-gendered clothes, and even confiding in teachers and therapists about a desire to transition. How can a newly minted adult make the choice to medically transition when for their whole childhood every attempt to explore their gender identity has been stymied?

My author’s note was going to encourage genderqueer kids who want to medically transition to be gentle and understanding with their parents. Because the reality is, if your parents aren’t on your side, you’re definitely not going to get any medical intervention. Advocates of trans care bans act like the status quo in blue states is that the schools and doctors will take away and forcibly trans your kids. That couldn’t be further from the truth. Getting trans care is exactly like every other form of medical care. As a legal matter, clinics need parental consent before making medical interventions, and as a practical matter, getting into care requires not just consent but active advocacy from parents. Clinics have long waiting lists, they can be distrustful of teens’ self-narratives, and they often don’t accept your insurance. There’s a learning curve for both parent and child that often brings them together and gets them used to the idea of transitioning.

But many parents and teens no longer have the option of going on that journey together.

In 2022, Glenn Youngkin took the governorship of Virginia, partly on the back of a ginned-up trans bathroom panic, and the fear of the parents in my book (which had initially been merely a pretext for their resistance) became frighteningly real. In early 2023 came the first trans care bans. At first it was only two bans. Then 10. Finally, 20. In the last version of my author’s note, I wrote that there was no ban yet in Virginia, but it could come at any moment. (Although the state currently has no care ban, the Virginia Department of Education last summer issued model policies for school districts that would force teachers to misgender kids, out kids to their parents, and prevent trans kids from using cross-sex bathrooms.)

The most important person in a trans teen’s life will always be their parents. And now parents not only have to worry about their kids, but kids also need to worry about their parents. I revised my book to take into account this fear of legal consequences: Tara is afraid to go on puberty blockers not just because she fears it’s the wrong decision, but because she’s afraid it’ll open her parents up to state intervention and potentially get them deported.

Because she’s conscientious and doesn’t want her family to suffer, Tara feels a strong internal pressure to deny her transness. And her anxious parents feed upon and emphasize those fears. They ask her, in effect, Are you sure? Are you absolutely sure? We’ll do it if you’re sure, but you need to be totally sure, because it might cost us everything. Tara isn’t being asked if she herself wants to bear the consequences of transitioning; she’s also being asked if she wants it so much that she’s willing to put her entire family’s well-being on the line.

In my book there’s a happy ending, but for thousands of families, this conflict will end in a rupture. Parents who move states or risk legal consequences for their trans kids may come to resent their kids’ “selfishness” for being unwilling to “wait a few years,” while the teens who are left behind in anti-trans states will resent their parents both for the guilt trip and for the years unnecessarily chopped out of their childhoods.

Both sides are right to be mad! The stakes are extremely high. However, their anger should not be directed at each other, but rather at the lawmakers who’ve forced them into this antagonistic relationship by passing legislation that forecloses the possibility of peaceably exploring the idea of transitioning together.

The burden on trans teens can only be eased once adults start understanding the life-changing power of gender-affirming care. In my novel, after Tara finally goes on hormones, she has the experience so many of us had, where weeks or days into our treatment we realize we can never live again without cross-sex hormones. The discrimination and legal consequences are a lot easier to bear once you’re healthy, whole, and fully embodied. It’s only at the end of the process, after kids have fully transitioned and become healthy and happy adults, that many families are able to understand the true tragedy of all the years of intervening delay.

If anything gives me hope, it’s the fact that so many families across this country have already made such immense sacrifices, up to and including the risk of legal sanction, to support their trans children. Trans kids are unbelievably courageous, but no less courageous are the parents who are able to ignore their memory of that screaming 3-year-old saying “MAKE ME FLY FOR WEAL!” and instead pay attention to the very real, very serious teenager who comes to them saying, “Hey, I think we need to talk …”