Vanessa Joy completed the paperwork to run for a seat in Ohio’s state legislature using the legal name she’s held since 2022.

When she returned to the Stark County Board of Elections office in December, she recalled the thrill of presenting the slate of signatures from those supporting her candidacy. But that excitement turned to dismay this month when she was told she was disqualified from running after leaving the name she used before her transition — known as a deadname — off her election forms.

“I thought I was doing everything right. I should have been on the ballot if not for this law,” Joy told The Washington Post. “The law is so obscure and unknown in Ohio, it appears the boards of elections for other candidates didn’t even know that it exists.”

Joy is one of three transgender women whose candidacies for Ohio House seats have been challenged under a little-known state law that requires disclosure of previous legal names on election documents. While the law isn’t new, some advocates fear it’s being used to hinder transgender candidates, and regardless of intent, it has ensnared several such contenders this election cycle in Ohio, raising concerns that trans candidates elsewhere might face similar hurdles when running for public office.

Days after Joy’s disqualification, two more transgender women running for state office were told that their forms were also under review.

“Ultimately, what it is, is trying to ensure that transgender people don’t get into office,” said Shelby Chestnut, executive director of Transgender Law Center. “It’s using existing laws in an effort to try and limit, and call attention to, transgender candidates to keep them from running.”

Ohio statute requires that anyone running for state office list all legal name changes from the last five years on candidacy documents. But Joy, Arienne Childrey and Bobbie Arnold told The Post they were never informed of the requirement. (A fourth transgender candidate is running for an Ohio state Senate seat, but he has not had a legal name change and listed his deadname on his documents).

Joy, Childrey and Arnold said they would have listed their previous names if they had known of the law. The candidate forms don’t instruct applicants to list previous names, and the statute is not listed in the state’s 33-page candidate guide. Ohio Secretary of State Frank LaRose, a Republican who oversees the state’s elections, said through a spokesperson that the name requirement could be added to the guide in the future, but stands by the application of the rule this year.

Multiple experts, including Chestnut, told The Post that they could not recall a case in which the law had hindered previous candidacies. It’s not immediately clear what prompted Joy’s candidacy paperwork to be reviewed, but after her case arose, Arnold and Childrey were informed that their respective counties would review their candidacies as well. The outcomes in each case have been decided by the candidates’ local election boards, leaving a patchwork of results: Joy remains disqualified, and Arnold and Childrey remain on the ballots.

Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine (R) is calling for a change to the policy, telling Cleveland.com last week that transgender candidates shouldn’t be kept off ballots for omitting their previous names on elections materials. The Ohio Secretary of State’s office said in a statement to The Post that, while there are no immediate moves to change the law, officials will examine ways to make the requirement clearer to candidates.

“The Secretary feels it’s important for people to disclose who they are and any former identities, so the voters know who is asking to be put on the ballot,” said Melanie Amato, a spokeswoman for the office.

All three candidates are Democrats; Joy was running in Ohio’s 50th district; Childrey is running in the 84th district and Arnold is running in the 40th.

The Stark County Board of Elections informed Joy on Jan. 2 that she would not be certified to run for office, citing the omission of her previous name on the forms.

She appealed the board’s decision on Jan. 5, arguing that she was not aware of the law and did not intend to mislead the public. The board rejected her appeal Jan. 9, officially disqualifying Joy from this year’s race for the House seat in her district.

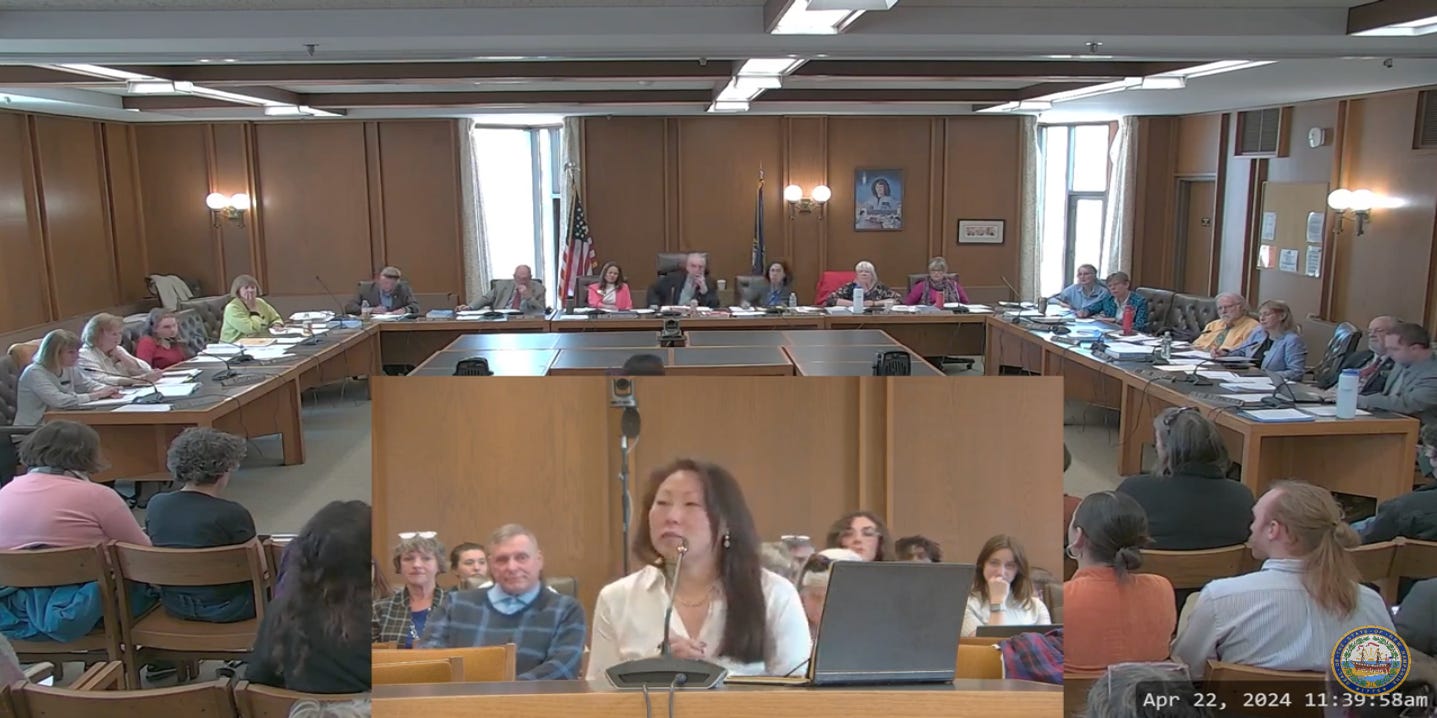

Meanwhile, the Montgomery County Board of Elections notified Arnold on Jan. 8 that it would review her candidate documents. The board on Tuesday determined that Arnold did not intentionally deceive the public and that there was no reason to disqualify her, according to Arnold. Board director Jeff Rezabek told The Post that he has not seen this issue come up before.

“I am elated that they made that decision,” Arnold said. “This law, while it was necessary for the spirit of what it was created for, which is to keep nefarious people from changing their names to run for office, it’s almost discriminative in how it is applied to trans people. Because that’s not what we’re doing: we’re not changing our names for nefarious reasons. It is to better reflect who we are.”

In Childrey’s district, the Mercer County Board of Elections met for just about “five minutes” on Thursday and decided she could proceed with her candidacy, Childrey told The Post.

“We’re relieved for what happened with us, but it exposes what we said all along: how wishy-washy, how unclear things are in Ohio and frankly, how selectively enforced this is,” Childrey said, pointing to Joy’s local board still keeping her from running.

After learning of Childrey’s and Arnold’s outcomes, Joy appealed to the Stark County Board of Elections once more. “This leaves the Stark County Board’s decision to be the outlier by not allowing me to run,” Joy wrote Thursday to the board. “I respectfully request another reconsideration of my candidacy based on the rulings of the Mercer and Montgomery County Boards of Election.”

The Stark County Board of Elections issued a statement Friday standing by its decision to disqualify Joy. The board “is sympathetic to Vanessa Joy’s argument that the campaign election guide put out by the Ohio Secretary of State was not specific enough. However, our decision must be based on the law and cannot be arbitrarily applied,” it said.

It’s unclear how many states have a law like Ohio’s, said Sean Meloy, the vice president of political programs for LGBTQ+ Victory Fund, an organization that aims to elect LGBTQ+ people into public offices.

A record number of transgender candidates ran for office last year, and as that trend is on track to continue this year, Melov said he’s “very worried” that similar laws may be used to challenge transgender candidates nationwide. It may also be a deterrent to would-be trans candidates who are reluctant to surface their deadnames.

Childrey’s, Joy’s and Arnold’s campaigns for seats in the Republican-controlled Ohio House were called into question as almost half the states in the nation have passed laws targeting transgender people. In Ohio, lawmakers are considering multiple bills related to the transgender community, including an attempt to ban gender-affirming care for minors.

Joy, Arnold and Childrey said attempts to legislate transgender lives are what compelled them to run. What they view as a targeted application of an Ohio law to hinder their runs for office is alarming, they said.

“Do I believe that this law was written to target trans people? No, I do not,” Childrey said. “I believe that it’s become a convenient tool for some bad actors to latch on to, in an attempt to silence trans voices that are speaking out loudly.”

For Joy, it means that her candidacy is “dead,” she said. “I’m disappointed. But the next step is figuring out what to do with this law before the next election.”