Bubs is a robot that wants to be a woman. Not a human. A woman. She makes a living sweeping space debris from earth’s orbit, and, along with three other misfits—Captain Jang, Tae-ho, and Tiger Park—is envied by other space sweepers for her ruthlessness. Among the member of her gang, she is the stingiest and the one with the most money in savings. Bubs has a goal: she aims to transition.

Bubs is humanoid yet faceless, with a white, worn-out, skull-like head, two lit dots for eyes, and an exposed mechanical neck. She tends to hide her torso under oversized hoodies and shirts. She is rash, strong, and calculating. Her ragtag group of friends appears to know about her goal, but the topic is rarely broached. In private, however, withdrawn to some corner of their shabby spaceship, Bubs daydreams of skin grafting, counting her money and the days until the procedure. At some point the group adopts the little bioengineered girl Kot-nim. Endeared, Bubs decides to entertain the child by doing her makeup. In a meaningful surprise, the child calls Bubs “lady.” Affirmed, Bubs blushes, her metallic cheeks turning red. “What did you say?” asks Bubs. “You just made my day.” She not only wishes to get skin grafts but also to alter her bone structure—both of which are illegal procedures, she confesses. She’s almost there with the money, but something is holding her back. “It’s just I can’t go through with it,” she says, “because I’m afraid people will laugh at me. But that’s just an excuse.”

A central protagonist in the 2021 South Korean space-western movie Space Sweepers, directed by Jo Sung-hee, Bubs is one of the few transgender robots in science fiction. Robots have long been veiled cyphers for transitional and dysphoric experiences. But these tend to be reduced to the more philosophical parameter of wishing to be human, the transition framed by the abstract categories of human and nonhuman (or inhuman and subhuman). The theme has been a cornerstone of robot stories, qualifying the substance and subjectivity of the mechanical (logical; dead) and the organic (intuitive; alive). This framework inflates the idea of transition, its desire and consequences, to the widest philosophical extent—humanity—with this counterintuitively narrowing the myriad potential readings of robots as speculative fictions.

The problem with “human” is that it means as much and as little as “robot.” They are but opposite poles of a joke that is forever prohibited from landing—mere comparative placeholders without ontological ground. Sadly, this equation has trapped robot stories for a century now, more explicitly in their cinema versions than in the literary world, which tends to be more expansive and riskier. I call this never-ending trope “android loop.”

By this I mean the constraining of android stories to the question of having or not having a soul—or emotions, or self-awareness, or empathy, or jealousy, or a fear of death, or faith in the supranatural, or even an idea of religion. Like the replicants in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep / Blade Runner, subjected to the Voight-Kampff test for empathy, androids have to eternally prove themselves. Either they exist like us—that is, as human—or they don’t exist at all.

Bubs’s transgender experience does not disavow this android loop entirely. But, grounded as it is in gender, it allows the android to break the mold and surprise us. It also liberates the relation between androids and humans from analogy or subtext. Bubs is literal in her transgenderness. Her desire for skin grafting and bone-structure change is expressed in a language typical of facial feminization surgery. Taken further, it can be read as breast augmentation, tracheal shave, and vaginoplasty. At the end of the film, once she has undergone her surgical transition, Bubs remains restless, continuing to perceive her voice as robotic—or “masculine”—and yet again it is the child Kot-nim who gives her sound advice: “I like how you sound right now.” Like many trans women, insecurities linger despite our transitions, the horizon hard to reach. Bubs’s answer: “Okay, just pick one, because I’m getting sick of the one I got.”

I find this image of a continuous transition particularly useful for dismantling the abstract vocabulary of the android loop and its overarching dichotomy of human-nonhuman. Before I transitioned, my dysphoria was generic and unlocalized; it was mostly a feeling which, yes, could be attached to body parts and performance expectations, but which was abstract nonetheless. It was something felt in a hard-to-define inside, rather than a discomfort projected onto my body. In this I have been lucky: euphoria defined me more than dysphoria. Counterintuitively, it was only after hormone replacement therapy that my dysphoria was quick to localize itself on body parts or the timbre of my voice. My personal journey took me from abstraction to particularity, from generality to specificity, from a lack of vocabulary to grammar. Instead of a placeholder, both empty of meaning and charged with philosophical judgement in its applied abstraction, the “human” is here a specifically embodied feeling.

As a transgender person I want to be seen as human. “Human” not as a hierarchical category of privilege and power, but of empathy—that is, the agency in being an emotive and relational being who sees comparison among differences as positive rather than excluding. “It’s just that I can’t go through with it, because I’m afraid people will laugh at me,” insists Bubs. We’ve all been there. But the human here is no longer a category of belonging, reifying a hierarchy of existences. It is an embodied feeling expressed through radical self-honesty. It is a soulful experience of love as the maximum expression of a consciousness capable of being shared.

Pinocchio is the prototypical dysphoric “robot.” A puppet recalling both early automatons and future androids, Pinocchio is moved by love, and because of love sees himself wronged. Why was he “born” in his wood and string body? In Steven Spielberg’s 2001 movie A.I., an adaptation of Isaac Asimov’s 1969 short story “Supertoys Last All Summer Long,” the android child David is compared to Pinocchio, and like Disney’s toy he too makes a wish to the Blue Fairy to transform him into a “real boy.” At the end of the film, having flown to a flooded New York, David waits under the sea in front of a statue of the Blue Fairy in what was formerly Luna Park in Coney Island. Time passes, a new Ice Age comes and goes. David’s wish lasts millions of years; it is stronger than time, stronger than death. David wishes to be loved by what he feels himself to be, regardless of his body.

While the main quandary with androids is that they have a body but must strive to prove they have a soul, AI struggles with the opposite: artificial intelligence is pure mind without a body. Both avenues lead down the same rabbit hole: the inscription of the duality of body and soul as a discriminatory guideline. But it gets worse. For if one were to surpass this duality, one would find yet another duality—between soul and mind.

The modernization of subjectivity has been a steady shunning of the soul: its sterilization either into biological mind or psychological emotions. Only at great cost does any abstract sense of being between emotions and mind survive today, as if the scope of one’s existence could be easily squared between psychology and reasoning. To attempt a definition of soul would be ridiculous, for it is ungraspable; still, soul might be felt as not simply a sense of self but as a greatness beyond self. If mind is affirmation, soul may very well mean humility. However, it is curious that when judging androids, what is often invoked is the soul, for a mind, understood as reasoning, is something they appear to have. Whenever there is duality, reduction is the name of the game.

“Passing” is a key word here, implying that androids and AI are not only mock souls/minds but also mock bodies. Androids are human-passing robots. They are robots in drag. David/Pinocchio will never be “a boy” because, even if his soul is proven by love, his body is not a real body. The binary is continuously and slyly reinscribed, either through the veracity of the body or of the soul/mind.

“Passing” is a tricky word for a transgender person. It may be both affirming and demeaning, with the feelings oftentimes overlapping. For some it is not important at all; for others it is essential. At its best, “passing” means to be perceived as one is. I don’t want the eyes of those who cross my path daily, at a cafe, in a store, to go from a mundane “Good morning” to a quirk of the lips, a glazing of the eyes, upon the arousal of doubt. I often perceive this switch as a glitch, a malfunction of a determined robot; these people, to me, they are the androids. At its worse, however, passing suggests that one is not what one appears to be—an infiltration, a disguise. A rhetoric built on prejudice. This theater is a hypocritical illusion, of course: passing is only positive or negative in a world keen on the gender divide. Not that the divide doesn’t exist or that it is inherently bad; it’s just that the divide should not be the criteria for any of this. The divide owes its existence only to an adherence to the dogma of theoretical categories and societal norms.

Famously, the Turing test, conceived by Alan Turing under the title “The Imitation Game” in 1950, determined the authenticity of a thinking machine by cheating a person into believing they were chatting with a human rather than a bot, setting the bar for androids and AI as tricksters—a discourse familiar to transgender people. Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the gendered history of robotics as well as Turing’s own hidden homosexuality, the test was based on guessing the gender of the interlocutor: Was it a man or a woman? And yet the bot was only trying to pass because the humans put all of their faith in the pretense of passing.

Robots lead to the thorny and intertwined dimensions of sex, gender, and reproduction. Given that robots aren’t born but made, and that they aren’t meant to reproduce, why then should they comply with the grammar of sex or gender?

At the end of her many trials, Bubs makes it as a woman. And yet she was never a man to begin with. Bubs was built as a robot, neither masculine nor feminine. So where does her desire arise from? Androids and AI come with no predetermined gender, and definitely with no sex. When born, humans too have no intrinsic gender, the binary of female or male being attributed only by custom and a deep-rooted attachment to physiological differences. Sex is the defining element in this categorization, but the attachment of genitals, chromosomes, or gestational capacity to womanhood or manhood is aleatory. Biology performs perfectly well without words, all animal or plant species being perfectly happy in their ignorance of prescriptive roles to either actor in the coupling. The gender of robots is programmed—for us! And their sex too, if they have one, is customized for our pleasure, according to our libido, biology, and psyches. Above all, robot reproduction is fully prohibited, being sternly removed from gender and sex and framed as the ultimate sin. Again and again, the hierarchy is imposed.

In Karel Čapek’s 1921 theater play R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots), which first introduced the word “robot” into the science fiction canon, androids are made of flesh and blood, not wires. Closer to clones than machines, they obsess over reproduction, finding in their incapacity for gestation a sense of both mortality and destiny—a sense of injustice but also of struggle: a struggle against humanity. At the end of the story, having deposed all humans in a mighty war, the last robot cries in anger and frustration: “You gave us weapons. We had to become masters … You have to conquer and murder if you want to be people!” For androids, the desire to be human is a Faustian gamble. This last robot cannot reproduce itself and is thus destined to die. Its imitation of humanity—that is, its imitation game—is so good that the only possible reproduction is the reproduction of violence.

At this conjunction between sex, gender, and reproduction is desire—and with desire comes jealousy. Jealousy is often a difficult feeling to deal with because it is not a single emotion but, in fact, a bundle of them, ranging from envy and possession, loss and fear of abandonment, sadness and mourning, deep love and longing desire. A.I.’s sweet-eyed android boy David envies his adoptive mother’s biological son Martin. In return, Martin envies his mother’s attachment to David; after all, David is a toy, so why should she like him better than her own son?

Jealousy is difficult, but it can also be affirming. Gender envy, such as wishing to be a woman or a man and have what other women or men have, tends to be part of transgender experience. The trope goes like this: “Do you desire this woman or man, or do you desire to be her or him?” Jealousy feels disconcerting, acting both consciously and unconsciously; it is easily repressed, leading to resentment, but it can also bring to light inner emotional truths, push you onto the right path, and foster the strength to follow your intuitions. Predictably, jealously operates at the level of imaginary social codes, performances, and expectations, which, though you may know they are entirely fictional, are nonetheless hard to shake off. As a transgender person one learns to navigate between reality and fiction, knowing full well that reality and fiction are but two side of the same coin.

David envies Martin’s humanity—Pinocchio wants his wooden body to be flesh and blood—but above all he envies his love. The love Martin receives from his mother and the love Martin can give back in return. As a right, love, the android quickly understands, is exclusive to humans. Yet love is beyond property, and as such beyond hierarchies—in other words, beyond the fiction that we call humanity. Transgender (and android) jealousy confounds love—love for another, love for oneself.

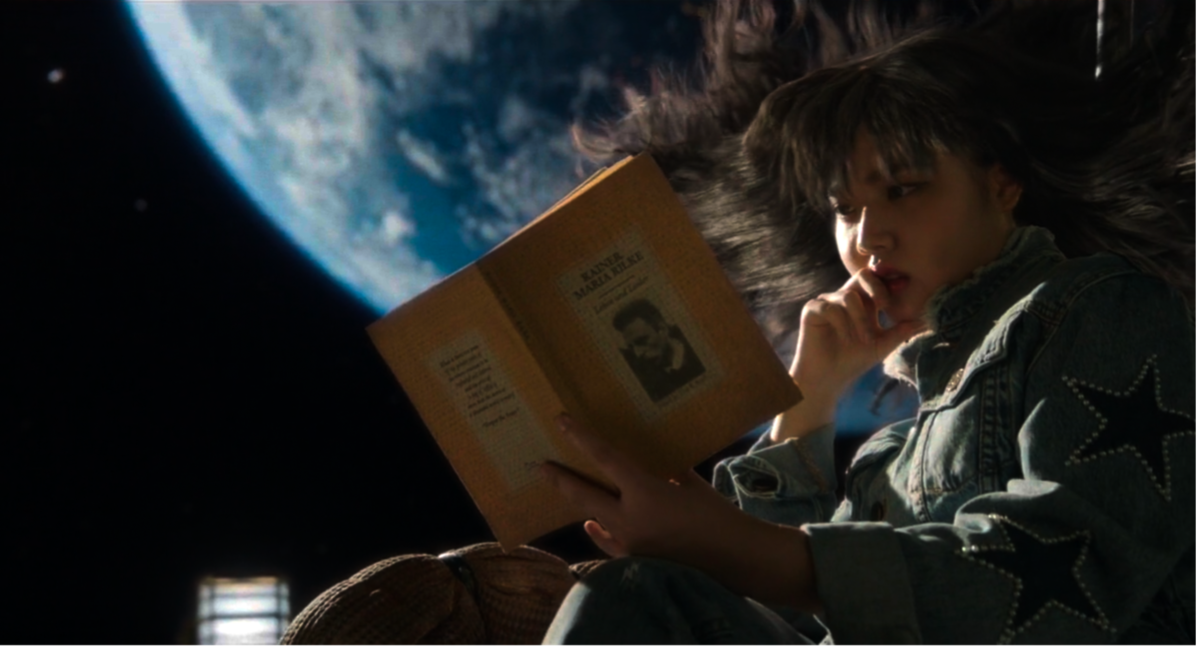

Once Bubs has undergone her surgeries and is finally aligned with herself, she nonetheless retains her original robot idiosyncrasies, such as the ability to function in space. A transition, after all, is an accumulation of features and not simply a swap. Transition is the act of traveling through domains on your way to maturity. And so Bubs sits on the ship’s hull, her hair flowing in zero gravity, beyond any XYZ axis, beyond heaven and earth, reading Rainer Maria Rilke’s debut poetry collection Life and Songs. A cryptic yet symptomatic reference: Rilke’s early infatuated poetry, nascent in its fabulation and adoration of feminine interiority, sex, and love.

Rilke himself was born “René” and was dressed up as a girl by his mother after she lost a daughter at a young age. This biographical detail is addressed openly by Lou Andreas-Salomé in the life-long exchange of letters she had with Rilke. Andreas-Salomé was Rilke’s lover and intense sexual and intellectual partner during his early adult years—the convergence between sex and intellect being a predilect topic of Rilke’s poetry. Lessoned in Freudian psychoanalysis, Andreas-Salome traced back to Rilke’s childhood his restless and soul-searching mood, as well as his preoccupation, in his poetry, with the female sensorium. Ironically, however, Andreas-Salome deemed “René” too feminine a name, making him change it to “Rainer”; whether android or human, it’s hard to free one’s mind fully from dogma.

Rilke’s feminism verges on a sacred, atheistically Christian idealization of femininity, yet it is synchronous with Bubs’s transgender baby steps into her new puberty. It makes sense that Bubs would find a romantic meaning in Rilke’s poetry. As the child Kot-nim says of Bubs, “She wants to be a sophisticated lady.”

Transgender puberty is a poetic stage of self-examination: a crossing into a craved-for desire that cannot but cease to surprise you for its irreverence. In this process, gender is disturbed by desire, and because of desire gender always escapes. You become what you felt you were—the feminine, the masculine—and yet what you are becoming is not what you felt; it is a difference. For those of us on hormones, we are well aware of how this crossing fully rewires one’s metabolism, physique, and emotions, confusing any duality of body and mind, of gender and desire, and, through a game of expectations with no winners, of the individual and society. Confronted with those expectations, difference positions itself and ridicules you, one’s self-image close enough to touch yet always at bay, the other always and already a part of you. Better to learn with the ridicule, for it is in those gaps that you mature and change. That you learn the meaning of love.

I wonder what Bubs found on that other side of gender and humanity, both of which are artificial, as she well knows. Her jealousy, after all, is sophisticated like her tastes: she not only wishes to be a woman, but also to have a gender to begin with. In her soul she knows that she is more than what she presents, more than metal and wires. In certain ways, she does not need to transition in order to finally be human; after all, she is perceived as an equal by her gangster peers, her chosen family. This much she always knew: gender is a mark of the human—for only those considered human, in comparison to a robot, are allowed to have it. But it is transition that also reveals to her that humanity is a falsehood—the wrong arbiter to begin with. In becoming the woman that she is, and through her transition claiming a gender where there was none, Bubs learns that love is nothing but the acknowledgement of the gaps between any duality. Love is a bond, and a bond is a space in between: an interval. How easy, then, to see robots as ourselves.