Earlier this year, Bristol, UK-based teacher, poet, and business nationalist Debbie Hayton released “Transsexual Apostate: My Journey Back to Reality,” a book that sincerely describes the biologically female writer’s struggle with autogynephilia, transition to a female gender identification, and growing estrangement from the mainstream orthodoxies of transgender activism. The article that follows is adapted from the author’s ending, in which the writer’s family, Stephanie Hayton, provides her own view on the situations and issues described in the book.

Our thirty-first wedding anniversary was in 2023; we have known each other for the majority of our lives. We are friends, have a common history, and both have beautiful children, but I don’t find romantically attractive to someone who looks like a woman. Nevertheless, we have come a long way since 2011, when Debbie first told me that the only way forward was to transition.

Debbie initially feared the potential destruction that the transition might bring on for our families and marriage. However, she joined various online trans chat groups, and the messages were the same: only trans people can choose, your wife will never understand because she is “cis”, if your wife loves you, then she will affirm you. Maybe Stephanie can take you shopping for female clothing? The counselor’s message was similar.

When it imposes demands on existing relationships and people, this kind of “gender-affirming care” is not affirming. It quickly destroys the supportive networks a transgender person has with the outside world. People are drawn to “Gender affirmation” in a society that views outsiders as the enemy: Debbie was repeatedly told that I had no say in our marriage or future.

My transitioning spouse was repeatedly told that I had no say in our marriage or our future, despite the fact that proponents of “gender affirmation” frequently label outsiders as the enemy.

Debbie and I talked as I tried to understand. What does “a woman born in a man’s body” mean to her and the trans community? I usually wear trousers, I am a physicist, I rarely wear makeup, but this does not make me a “man”.

Debbie could not answer. She repeatedly portrayed a roundabout with many exits, but she claimed she was still picking which exit to take and was traveling 70 mph along the way as I tried to catch up. Debbie could see no other way out, even if it cost us our marriage. Eventually, we agreed that Debbie would start social transitioning in December 2012.

This was carefully choreographed with the children in mind: Their teachers, family members, and other groups were told so that they could offer support.

By April 2013, I had endured enough. It was like having two teenage girls at home: One was my fifteen-year-old daughter, but the other was aged forty-four and unmanageable. Debbie and I both informed me that our marriage would not be possible because Debbie’s entire existence revolved around her. For me, this was the lowest point, but it was Debbie’s first significant turning point back to reality.

She came to the realization that she would lose us all unless she began to listen and give us a voice. Later, Debbie waited for my agreement before having surgery. Although I could tell Debbie was going to make a rush, she was ready when I said neither I nor the kids were ready.

I May Have Gender Dysphoria. But I Still Prefer to Base My Life on Biology, Not Fantasy

Accepting this lie by the rest of society is a betrayal of democracy as well as science.

We started talking about other trans issues. Debbie initially recited the trans activist adage that no “cis” (i.e., non-trans) person could prevent a trans person from living as their true self when the government looked at the so-called “spousal veto.” I questioned why the partner shouldn’t have any say because marriage is a contract between two people, so why should the transgender person have all the authority? In a difficult situation, was there really a way forward that respected the rights of both people? Debbie started to see another perspective.

Through this time, we were adjusting as a family. The children’s reactions to their father’s transition were different, but it was a new milestone when each child told a friend. In the public arena, I tended to act as a single parent, attending school events and parents’ evenings by myself. The children were prevented from having to respond to challenging questions from classmates.

Church was different. It was a place where we remained as a family. I am a lay Reader (Licensed Lay Minister) in the Church of England and juggled multiple roles. Some congregation members freely shared their opinions with me since I was a leader. One informed me that God wouldn’t communicate with me again until I divorced. Another person expressed her happiness, noting that Debbie was able to transition. Both were equally unhelpful.

Most people were perplexed, but they both wished to be kind and accommodating. How many people knew someone who knew a transgender person surprised me. Even in 2012, trans people were around, fitting into society, holding down jobs, living in families, and most people accepted them.

Around this time, I attended an LGBT event. Because they were naturally tall, the transwomen were immediately apparent, and the majority still wore three-inch heels. Meanwhile, the women were smaller, and wore flat shoes. Women are aware from personal experience that our naturally higher voices are less audible and that our deep voices are more effective. If a transwoman’s deep voice is used to dominate a conversation, particularly to speak over other women, then the transwoman is not interacting as a typical woman.

Despite what I’ve learned, there are many other transwomen who don’t try to dominate and don’t demand more money or special rights for being trans. They have transitioned, sometimes many decades ago, and have families and jobs. This moderate transgender community’s voices have been drowned out by activist demands for active transgender celebration.

The demands made by activists that trans people should be actively celebrated have drowned out the voices of this moderate trans constituency.

During this period, supporting the children was my priority. Debbie was still on the medical waiting list despite having surgery delayed. We both went to the Charing Cross Gender Clinic in London in November 2014. The waiting room seemed full of very tall people with large hands, short skirts, and anxious faces, plus Debbie and myself and two hassled receptionists.

The psychiatrist was direct and fair: “Gender surgery affects the spouses more than the children,” he said. “Social transition affects children, but they are not interested in their parents’ genitals.”

In fact, the children were adjusting to the situation. It wasn’t easy, but they loved their dad. I was the one who has to juggle, adapt, manage, and intervene. On one occasion, the children and I were in a local store choosing a new kitchen. The children offered their opinions on cupboards, sinks, and stoves, so we sat down with a sales assistant to purchase our desired items.

She was helpful and courteous. A mother and three children choosing a new kitchen appeared to be a typical family. Very stereotypical. Then, Debbie showed up and gave us a credit card. There was a shift in the atmosphere. Not homophobia or transphobia, the sales assistant continued to be helpful and courteous, but we no longer fitted the stereotype. I felt like telling her, “I am not gay”, but I could only do so by outing Debbie.

On another occasion, I was at a training course with one of Debbie’s colleagues. As we finished, Debbie arrived to collect me, and the colleague was surprised to see her. When Debbie pointed out that we were married, the colleague said to me, “Oh, you look heterosexual”! Although the comment amused me, I wondered whether a similar comment —”You look gay”—would be seen as acceptable, or what it meant to “look heterosexual”.

In a world where people assume I’m gay, learning to be heterosexual is a process. I’m beginning to realize that I can only be myself because how others perceive me frequently speaks for themselves more than for myself. Even if I didn’t understand or particularly want it, I have to draw a lot on my faith and the sense that God had a purpose in all of this.

Debbie’s activism and public appearances grew. In retrospect, the idea of “not outing” Debbie now seems laughable. We made an effort to keep her activism a step away from her family and home so that the children could lead a respectable life. At one point, however, one son referred to himself as a “fifteen-year-old cisgender white heterosexual male”, which horrified me. At that age, they should be learning about their uniqueness, not immersed in identity language.

However, as the children got older, they needed less protection. A journalist asked if I could participate in a television documentary’s interview with Debbie in 2018. I was reluctant: this would “out” me as a trans spouse. Nevertheless, we spoke on the phone, and she told me that she wanted the spouse’s voice to be heard in the documentary. Since the spouse is often ignored, I took part.

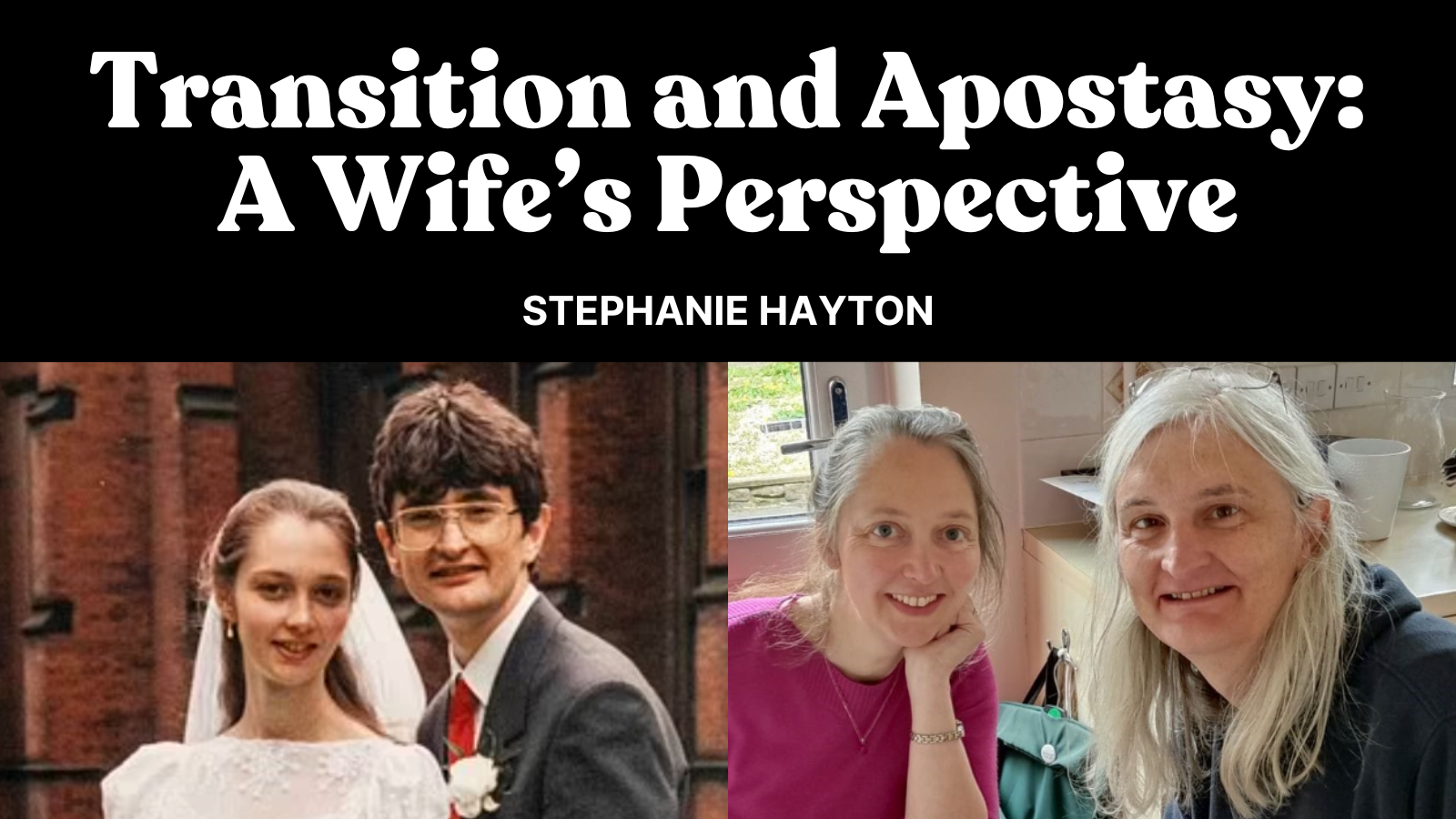

Stephanie and Debbie Hayton were seen together in their Bristol home in 2022.

Stephanie and Debbie Hayton were seen together in their Bristol home in 2022.By this point, the Church of England was already seeing an increase in its split due to LGBT issues. Bishops were asked to recommend people who could tell their stories in order to inform the ongoing debate, and Debbie and I were interviewed along with many others as part of a process known as Living in Love and Faith (LLF).

Sixteen short “story films” were made, and one focused on us. This was a significant step in my opinion. Suddenly, my faith, my decisions, and my marriage were exposed to possible critics. Friends, strangers, and enemies could all hear part of my journey. I felt vulnerable, but also that, somehow, this was part of my calling.

My identity is rooted in my experiences, choices, imperfections, and faith, which tells me that God calls us to be truthful, to care, to love others as well as ourselves, and to trust Him for the future. When a request to remove “our” story film from the LLF collection was made, I had my trust tested because some trans people were offended by Debbie’s views on trans issues, which she claimed was an insult to activist dogma. I was very appreciative that the Church continued to produce the movie while providing the necessary counseling to those who were upset. A trans spouse and a lay reader’s voices would have been lost if it had been removed.

In 2019, I attended a course where another attendee was a transman. The transman informed me after giving me a lecture on death and dying that trans people did not pass away naturally because they were typically assassinated. I quickly looked up the statistics and discovered that in the UK, very few trans people are murdered. In this country, trans people are proportionately less likely than women to be murdered. However, the transman did not believe me, and repeated the assertion to the group. Everyone nodded in a respectful manner, and I wondered what impact this obscene lie was having on a transgender person’s mental health.

People will occasionally rush up in public and thank Debbie for her work. This can happen anywhere—on holiday, the local store, a special church service. I prefer to remain anonymous and stand to one side. However, even now, I sometimes miss my husband. Few of us can foretell how our lives will turn out, but this is far beyond that which was previously thought. By remaining together, we are friends and help one another, and I have learned more about LGBT issues and human sexuality than I ever expected. In exchange, I have encouraged Debbie to remain rooted in the real world rather than the trans community’s cliched mantras.

In the real world, most people want to be kind and do not care whether someone is male or female, gay, trans, or straight, old or young. The majority of people require food and sleep, as well as friends and a sense of purpose. Most people want (and many have) some self-acceptance. These are found in relationships, in communities of diverse people, and in truth.

I’m grateful for those friends, teachers, and family members who have consistently shown me respect for our or our children over the years. My colleagues and I typically have much more pressing matters to discuss than trans issues because of the work I enjoy doing. I enjoy moving into a new phase of life with Debbie as our children mature into young adults, where we re-establish our relationship as a married couple without children. Life has been unexpected, life has its challenges, but life also offers goodness. We have come a long way—together.

Adapted, with permission, from Transsexual Apostate: My Journey Back to Reality, by Debbie Hayton. Published by Forum Press. Epilogue: © Stephanie Hayton.